Eva Pascoe: It’s fantastic to be here. I’m really privileged to share this talk with you because it feels quite special, you know. I think everybody understands that something is sort of happening, we just need to move it along a little bit faster.

But I just wanted to check one thing: how many of you check your phone as the last thing before you go to bed? Right. Most.

How many of you walk on the street with your phone in your hand, bumping into people? Right.

How many of you met a girlfriend or boyfriend on the Internet? Oh, there is future. There’s always a chance.

Right, could you take your phone and swap it with your neighbor and let them have a good roam around it? [laughter] Come on, come on.

See how difficult it is. These are such intimate little objects that we’re not prepared to share them with just about anybody. But we share them with about a million people in UK who have high-vetted surveillance clearance to have a good look at everything that’s on it.

Audience member: But they’re not allowed to monitor phones.

Pascoe: Well, they’re looking at what you do on your smartphone.

Audience member: [inaudible]

Pascoe: So what’s on the data, the data that you look last thing before you go to bed? The email your check first thing in the morning? You’re sharing that activity with quite a lot of people. So today we just want to take a quick look to see how we can unfuck what happened over the last few years.

So when we started in 1994, Internet was an incredibly innocent little creature. We were terribly keen on sharing, connecting, and bringing the goodness to the world. Mainly because I was teaching nurses computing, and one thing I realized, that the best way to teach that is to bring people together to share it in the same space. So not giving them exercise to go home but bringing together. And I somehow discovered that by bringing them together and putting a bunch of computers around, it really kind of created spirit of the group and people were able to crack even the worst statistics in math lab.

So we put it out on the high street because we created a situation where everybody could learn connected to the Internet, and these were the first things we had. So Eudora, Mosaic, FTP, and a very very cranky, slow connection from Easynet. And you know what? Now look at it, what do we do today? We still do it, we just iterate it a little bit more on the topics. But they’re still the same functionality, so essentially nothing has changed, it just got a fraction easier and a fraction faster. Not quite fast enough, as some people in Hebden Bridge I think noticed. But the fiber is coming, apparently.

But what has changed since then, it’s a lot of other things happened. I’ve done a lot of crypto work, and I was behind a team that introduced SSL in 1996 to the shops. Mainly because it was possible to buy stuff with credit cards. Well, before it wasn’t. Or you could but you’d be really crazy to do it. So I moved—after Cyberia, developing the whole cybercafé concept, I moved to Topshop. Worked with Philip Green and somehow persuaded them that SSL was strong enough to let the crowds on it. Little did I know that you know, SSL was a big war that was just about to happen. But we did it.

And so things developed fairly slowly and in a trusted way, ie. we thought that we were developing things, not knowing what was going on behind the scenes. And the first sort of big war that I was involved with was the cookie wars. Because as you remember, the cookies were necessary for commerce. They hold the sessions. So they allow you to actually create a transaction.

But what they also allowed is the advertising crowd showed up. Before there were not quite enough people to do advertising online. But about ’96, ’97 there were enough, and all the advertising industry woke up saying, “Aha! This is people who we can sell stuff to.” And they decided to create “bad cookies.” So the cookies that we’re still pestered by today, who remember your data, who know exactly what you do, who will keep track of you in a way that you probably wouldn’t want to.

We lost that war. That was the first time that the commercial world won against the engineers, because to them the Internet was run by engineers and whatever they said, went. But that was challenged, and actually for the ones who remember it was Mark Andreessen who was in the bad camp. So when he suddenly emerged from using open source and being the good guy and shifting toward supporting the advertising industry we thought okay, knives out, gloves off, this is war.

And this was war that we kind of fought and lost till about 2004, when Google decided to create a business model on reading your email. And today we accept it, but then it was so incredibly shocking. The idea of a business opening your email, opening the most intimate of your communications and somehow making money out of it, it was just unthinkable. They knew it was unthinkable. So Eric Schmidt kept saying, “Oh well, you know, we get up to creepy but we don’t quite cross the line.” And I thought well…creepy depends on whose definition of creepy. Because for us it was pretty bad.

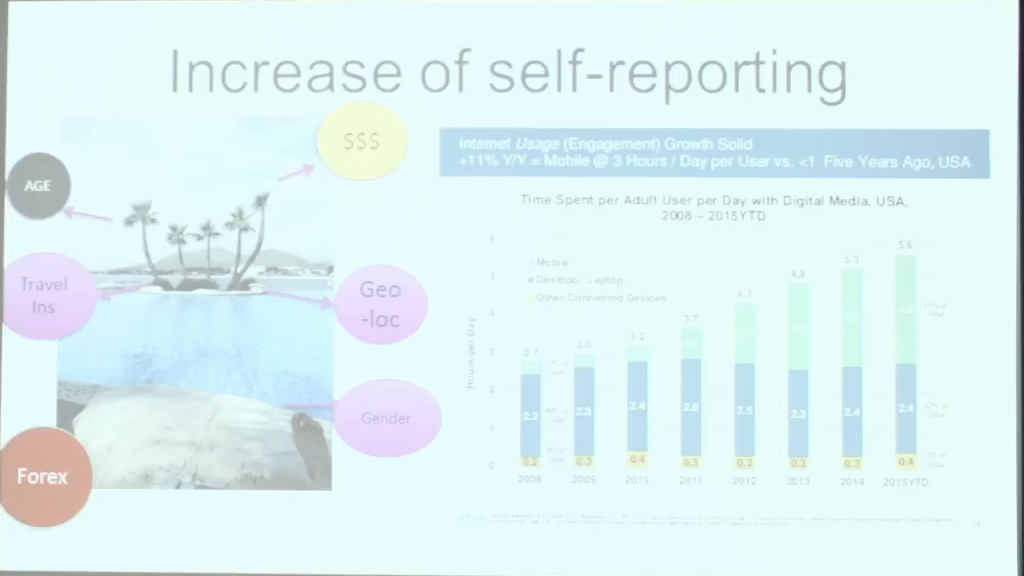

But again, the commercial world won, carried on. And we just kept feeding it more and more. Because if you look at the average Facebook photo… I love the Facebook photos with the feet. People always think, “Well, I won’t take a selfie because that’s a bit too vain. But I’ll put my feet there.” And they feel that that somehow gets them out of being tracked by data. And when you look at image recognition, it’s very easy to define if the feet are of a male or female, and if it’s young or old. So you can generate quite a lot of information from a little two feet.

You can also generate a lot more information. Where have you been? How much did you spend? How much money do you make? You immediately become a really nice stream of data that’s just flowing out. You did one little photo. Meanwhile, everybody—it will be like hundreds of cookies…advertising people just checking, registering, and creating your lovely little stream of data behind you.

And we didn’t really ask for it. We didn’t particularly create a business model based on advertising. But it is the easiest model there is. And we have to recognize that because it does pay for a lot of good stuff. But if you look how invasive it is. This is just the top of the iceberg. There’s probably around seventy data points that you can derive from a fairly average picture.

And the amount of time we spend online is just growing up and up and up. So at the moment, I think kids spend an additional five hours per day on the phone. What were they doing before? It’s kind of difficult to understand until you realize it’s all multitasking. So this is not new time. This is the time that they do something else, or we do something else. So we walk on the street, and for twenty minutes between your work and your bus stop you are on the phone. Before you were just walking. So a little bit, step by step, we’re not just doing one thing but we’re definitely tending towards doing two or three things at the same time, one of them involving a phone. So the average time on the phone at the moment for the teenagers is almost longer than they—I think it’s more than they sleep. I think the numbers are it’s more than they sleep. And I wonder how many of us can actually look at the number of hours spent on the phone, and is it close to how much we sleep? I bet it’s coming there.

So, one thing which we kind of missed is the whole growth of cloud computing. When we had little floppy disks, you couldn’t really put that much on it. So if you wanted to spy on somebody, it wouldn’t be terribly satisfactory because the amount of data wouldn’t be really sufficient to do anything with, plus it wasn’t accessible. Now we’ve gone to the cloud, it’s infinite what can be stored, and it’s terribly accessible even if you follow all the procedures and try to make it secure. Cloud essentially at the moment is not particular secure. So the data is just floating out there.

So we have the massive increase of data self-input. We just put the data in. All the time, almost ten hours per day, just data goes in. Social media, selfies, GMail. And also the drones, which created additional data points. You can see it more and more in Shoreditch, people kind of trying to investigate “is there a queue in the nightclub before I actually bother to go out?” I think it’s probably on the verge of illegal but you know, people do it.

And also cash. One thing we’ve noticed over the last two years, that cash is going. So, mobile payments are partially part of it, but obviously cashless. And when cash goes, data of your payments becomes digital, trackable. You can keep it, you can analyze it. It’s a nice little pile of your daily information.

And the algorithms to interpret are getting smarter, sharper, and faster. So, the combination of increased storage, very low cost of storage, and the ability to process it just handed over a massive advantage to spies.

So we make it harder and harder on ourselves, because even if you look at selfies, they were bad enough as selfies. Now people have selfie sticks. So I work very close to Oxford Street and I tell you, it is lethal to try to get through the tourists doing that and that. But its now double the amount of people. Because the selfie stick allows you to take a picture of two people, three people, four people. So yet more data coming in, and more facial recognition to train the algorithms on. So the whole thing is just speeding up faster and faster.

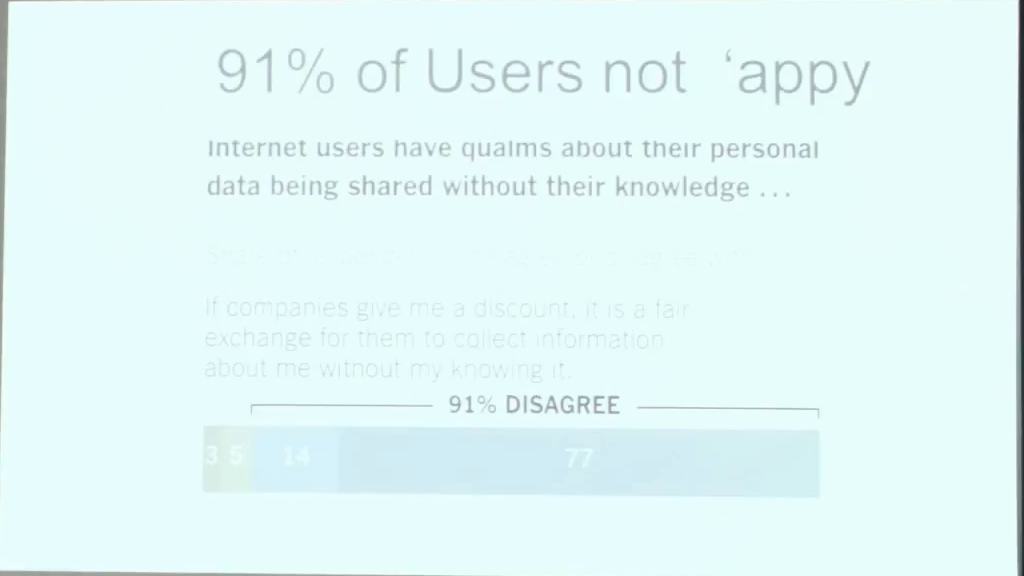

But the users are not happy. When you look at research— There was a big research by Annenberg Foundation about six months ago. It’s not that people accept it. They are resigned to accept it. They’re saying, “Well, we’re not happy.” 91% of a quite big study was definitely not happy that their personal data’s being shared without their knowledge, kept by records and with unknown use, or use that is commercial against them.

But what happened is that they think that there is no other choice. That it is what it is. And they might feel guilty about ad blockers. Which we discussed before, but ad blockers is another big topic. So when you look at the value exchange, what people questioned, they’re saying, “Who gets my data? I don’t know. How much is it worth to me? I don’t know that, either. Can I revoke my permissions? Well, I don’t know. How do I lock permission based on time and place, because sometimes it’s okay to have my data but not the whole time and not when I’m not aware about it.” We don’t really have that conversation with the advertising community at the moment. They just take everything, at any point, all the time.

We did quite a big project, which I want to just quickly tell you, where we allowed people to share data within a specific time. So when girls go shopping between two o’clock, five o’clock on Saturday, it’s okay. Have my data. I can tell you where I am. Location on. Everything. Because I’m kind of expecting at that time you will offer me advertising deals and it’s fine because I’m in a shopping mode. But at five o’clock I’m going to do something else. I don’t want anybody to know anymore. So I switch my location off. But that’s not enough because there’s still a lot of data flowing around.

So what we found is that people are quite happy to do it if it’s contextualized. So if it’s from/to, or certain places but not others. But we haven’t got a formula to negotiate that with. So our kind of current thinking is probably the platform to own the data has to be the town. So Hebden Bridge, or York, or Shoreditch, of something that people actually have emotional attachment to, that they think they belong to the tribe of that location where the data is held by a portal that they can go back and negotiate with.

A few people are trying to do it. But the attachment to the security is definitely local-level. So when we did that research it was in town. It was in North London. So if the data is held shared by local council I can just about live with it. But any further, no. So it will be interesting to see how our identities develop in terms of their locale, and then what’s further. And how far the trust goes. Who are you prepared to give the mobile phone to? Your mayor? Your councillor? Anybody? At the moment we haven’t got that debate so we don’t know the answer, but our kind of pin in the map is that it’s very local. That people trust locally.

So at this stage we got together with Tim Berners-Lee, who is promoting something called the “Digital Magna Carta.” And Tim had this idea, straight after Snowden pretty much, that something needs to be fixed, and promoted a concept of a certain bill of rights for digital users worldwide. And it’s a very very interesting proposition but it’s global, and law doesn’t work globally. Law works locally. So we got together with them and decided that let’s just try to see if we can trial it out for the UK. So we’ve got a project called Digital Bill of Rights UK which Tim’s foundation called the Web We Want Foundation supports, and they have that foundation in a number of different countries. So the Italians just got it. So the Italian bill of rights has just been presented to the parliament.

Our problem is that the UK is a very heavily surveilled country, and everything that we put in the Digital Bill of Rights, the government is basically against. So what Italy seem to be accepting, the UK has got a much longer time to investigate.

So we took the Digit Bill of Rights on the road, created kind of like a proper flip chart and Post-It notes and consultations and a little bit of an exchange of what people think on the topic of your data. Is your data your data, or [does] it belong to all the spooks? Is copyright something that we should be reforming? Which in the context of 3D printing is becoming very important because you can’t really 3D print Lego and not contravene Lego’s copyrights. We looked at cybersecurity and reform of surveillance. Because at the moment the surveillance in the UK is by appointment by the prime minister. And it tends to go to judges who are well over 70 years old. The last two appointments last week, both new judges on the commissioner’s circuit, are seventy. What do they understand of a surveillance algorithm, I do not know. But I wouldn’t hold my breath.

So the whole process of surveillance needs to be reformed. The oversight is at the moment under nobody’s control. So we’ve sort of thrown it out to see what happens. And one of the last things, which we just added because we thought it would be interesting to see. The right to digital education, but not as impassive, because the government talks a lot about digital education but all they want people to do is to be able to fill the form for unemployment benefits. If you can do a digital form, save the government a lot of money, you’re in.

But what we would like to see is still make sure that people actually have the tools to do digital work. To join the whole revolution and not to be just passive victims. And that was probably one of the biggest points for people. We got so many people saying, “Are the robots going to take my job away?” Or, “No no, our job is going to be fine.”

“So what do you do for a living?”

“I’m a clerk.”

“Er, okay. That’s probably yes.”

So we made a long list of jobs that are at risk. And it was a pretty long list. I don’t know if you’ve seen the new list which came out of from the Oxford Internet Institute about all the jobs that are at risk because of automation. So not so much physical robots that do things, but robots as in algorithms. And that list was incredibly long. So very very few things will be left once that particular steam engine revolution goes through. So when we are here, it’s very interesting to see that obviously this area has been very affected by the first revolution in a good way, and the second probably the worst way. But the third one will affect everybody wherever you are. It doesn’t matter where. So the way the work of algorithms is developing is basically a bunch of guys in hoods sitting in California remote controlling everybody. And at the other end they just need a body on a gig economy, two pounds fifty per hour. Enough.

Because all the intelligence is in the algorithm. And that has happened so quickly that we don’t really know how to respond. So, pretty much everybody will be unnecessary because the level of automation is pressing so fast that you only need a tiny handful of people. You know, I go to offices, I work with big tech companies. They’re tiny. Tiny. Like, Twitter…there’s a handful of people running enormous businesses. So when you go to IBM you kind of thing you know, “People are really working here. There’s hundreds over there. Two hundred there…” God know what they do all day but they kind of do something.

If you go to Reading area, Slough area, around London, they’re the sort of gold triangle of old tech. And it’s just hundreds of people running around looking busy. You go to California, and it’s [?] big buildings with black mirrors outside and there’s no one. There’s just the hum of computers, zzz zzz zzz. And the big data centers which do all the work. So the new world does not need people. So the issue of the digital rights has suddenly become quite pressing. So digital education, as in we actually want to be the ones who are running it all because there won’t be that much space for people who are not on that particular bandwagon, it needs to happen now. So when I listen to people like 3D printing guys you know, they are absolutely on the right path. But they are still slow. It’s still too slow. It needs to happen a lot faster.

So meanwhile, while we were trying to figure it all out and understand that actually what Tim has created, the client/server architecture, is wonderful but it’s a roll to only one direction, a centralization of everything in very few hands. Because if you build systems for a living like we do, if you can have one database you’re not going to have two. If you can have one of something, you’re not going to have two. So centralization, placed in the hands of a very small group of people. So centralization is power. And we bought into distributed networks that are not distributed. They are centralized as anything. So it’s a myth. If anybody tells you about distributed networks, it’s a myth.

Yes, you know, in a networking way you can bump one and the rest will pick it up, but it doesn’t mean that the database is not centralized. So we are entering in a completely different world where the number of people needed to do anything is very little, computers do everything else, and then we are the warm bodies at the end.

So it all kind of created a very different situation than we had before. Before we just didn’t trust the government. That was fine. But now we cannot really trust anybody. And I think that anybody started from Google, which has particularly kind of elastic ethics. Like whenever it suits them they just push it up and push it down. Apple is a little bit better because they have a better product, which can finance itself without data. But you know what? When they run out of that, they will be back with data. So it’s just temporary. So I wouldn’t feel too good about them.

And then you have Edward, who is sitting in Russia trying to kind of shovel everybody to understand a little bit what’s going on and get some awareness of citizen rights. Meanwhile the US government’s calling him a traitor. Very difficult to get any conversation. We had a really great event last year with Vivian Westwood, who is about 72 but she really gets it. So, she was interviewing Edward. One of the questions came up, do Americans understand human rights? Because they don’t really have human rights, they have consumer rights. So when you talk to American companies, it’s all about consumer rights. In which case it’s a very different conversation than a conversation you’d have in UK. So that’s why we decided to push on with the Digital Bill of Rights for UK, and for Sweden, and for Poland separately, to really flesh out how far we can push back. And how far we can buy a bit of time by circling some rights around us before the whole thing will be run by only one machine, one guy supervising it, and fantastic algorithms.

And I think people feel it, because we’ve noticed a lot of conversations on the Internet are going into code. So people came up with this emoji stuff, which took on like wildfire. So a friend of mine did the whole Casablanca in emojis. So this is, if you remember that, “What about Paris? We will always have Paris.” And people started using it more and more, and I think now the shift towards emoji is almost faster than using text. So I think there is a sort of underlying suspicion that if I talk in emoji at least people can’t really understand what I’m doing and track me. Which obviously is not true but people feel it is.

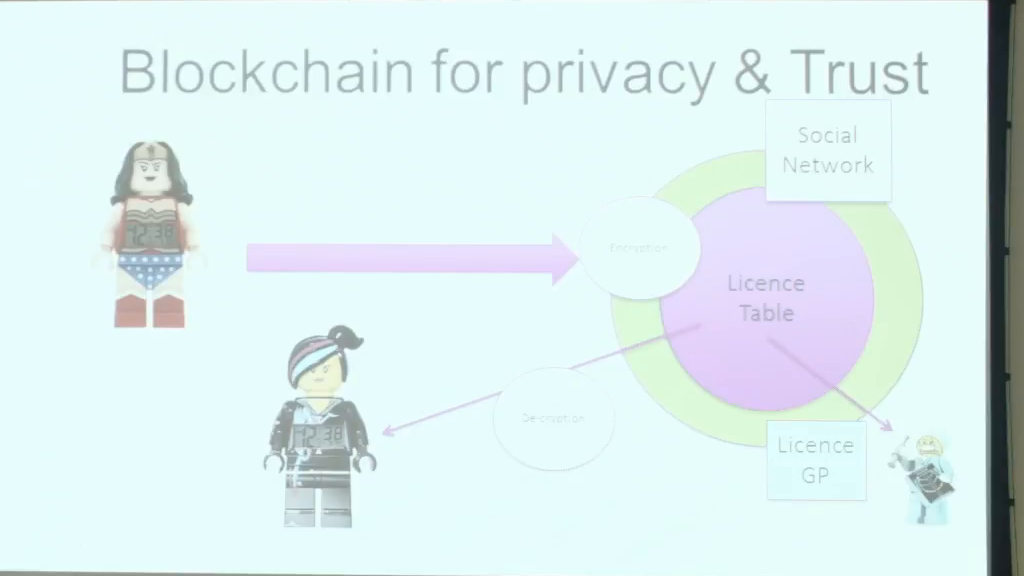

So, there is a group in Italy which is working on trying to put a little bit of a stop on the process and support people using social networks, and loading the data into social networks as we seem to like doing, but provide some element of encryption where you can choose who you share with. So if I want to share the data with my town, because I may want to benefit from collective data sharing, then I can say yes, the town is fine. But I don’t particularly to share datat with advertisers and I don’t want to share data with another town because we’re competing with this town. So they’re trying to work out a system that combines the ability to use social media but introduces layers of sharing permissions which you can put on or revoke in a fluid way. I’m very positive about it.

So, just to get the conversation more into what the Digital Bill of Rights could mean and what our protection could mean, if you look at the last twenty years, which for me were quite terrible because we started well and then it came out a bit worse. So what was supposed to be the beautiful community, sharing—you know, we were total hippies. We were crypto hippies, I think. It ended up being just one massive surveillance scheme. So when I hear the private equity and the data mode of database business plans, it’s just more of the same, and unfortunately I think it’s just finished eating its own tail. Because I don’t know if you’ve seen, yesterday there was a release of a new app called Peeple. Don’t know if you spotted it. It’s coming. It’s basically Feefo or Yelp for people. So if I met you today, I can go to this app and I say,“Oh, 5 out of 10 on looks, 2 out of 10 on honesty. Cooks well. Can run Apache…7.”

But if you piss me off, I will put “3.” A “1.” So, I’ve suddenly gained a power over everybody else for the split second where I provide some absurd, subjective rating but it goes into the system. So there’s a massive backlash against it, and I hope to God that it won’t happen. But you know, this is reputation management getting to the end of itself. Because we did very well on reputation management with Uber, Airbnb, the sharing economy. But I think when it comes to rating people? It’s probably too far.

So I’m sort of hoping that the private equity will just eat itself. You know, that the crazy ideas of monetizing everything to death, and our intimacy, our privacy, taking over the data that don’t belong to them, that they will just explode the whole thing by their own stupidity. So I’m very positive about it at the moment because I’ve seen this app…this is crazy. This is not gonna happen. But you know, you never know.

So my last twenty years, I think the positives, the real unicorns, are all about trust in good way. Where we trust in a positive way. Wikipedia. Nobody thought anything would come out of it, and I know people have views on Wikipedia. But you know, it’s there. Amazingly, it’s there, and amazingly it’s getting better. We do a lot of work on Wikidata, which I think is a total miracle because you can recreate pages in new languages without having to rewrite the bloody thing from the beginning, so it is pretty amazing.

And you know, this is just people sitting there doing a little bit here, a little bit there, packing it in. And one day you wake up and it’s…massive. Nobody gets paid. It’s really totally voluntary. There’s a very tiny team in California, but tiny. And it happened. So that gives me hope that the next twenty years can happen again, and a few of those will show up for open data, Mozilla movement. You know there are enough building blocks we can take it over.

I’m not quite sure how fast, but Wikipedia took a long time. It was really a very, very, very slow process. But when it achieved its sort of peak point, now it’s developing very fast, even in places where people are not particularly computer literate. There’s always a handful of people who can shovel stuff in and help others. We were in Athens last week, and the Greek Wikipedia is incredible. It is basically holding the data and information when the newspapers were manipulating it right and left and middle. It was down to Wikipedia to provide data. So, that is kind of over and above the old press. I think it might happen.

And blockchain. Again, it was sort of quietly bubbling along, but it is getting bigger and bigger and I think it could help us to create a situation where we don’t need banks. If I can be my own verifier because I own my own data, why would I need a NatWest? If I own my identity, why would I need Lloyd’s? We can do deals between each other. So, that’s quite a big threat for the financial community. I’m not quite sure they understand it, but they’re trying to buy into it just in case. But I think it’s developing as an alternative.

[This portion seems like it may be an excerpt from Q&A.]

You need the technical people to be the missionaries. There is no other way. You know, the technology will save the world before it kills it because there’s nobody else. In the olden days people were hoping that unions will save the world, or something will save the world. But that kind of didn’t work out. So it has to be technology and prototyping different ways, but it’s got to be the communication between the technical community and the local setting. And techies are not very good at that. We have to learn to do that better.