Can anyone tell me what this is? HitchBOT! Yes. It’s hitchBOT. What does hitchBOT do? He hitchhikes. HitchBOT asks people to put it in their car and take it somewhere, and as many of you have heard, this robot made it all the way across Canada and through some parts of Europe, relying purely on the kindness of strangers, and then two weeks ago hitchBOT was vandalized. It was trying to cross the United States and someone broke it beyond repair.

And honestly I was little bit surprised that it took this long for something bad to happen to hitchBOT. But I was even more surprised by the amount of attention that this case got. I mean, it made international headlines and there was an outpouring of sympathy and support from thousands and thousands of people for hitchBOT. They took to Twitter and expressed how sad they were. HitchBOT was attacked. HitchBOT is dead because humans are awful. Cecil the lion and Hitchbot the robot in the same week.

Now, you could say of course people are upset. This was an act of vandalism, and we condemn that, when people have no respect for other people’s property and they make it valueless. Not matter what it is, if it’s a car, we don’t like that behavior. But in this case it’s also interesting that people are apologizing directly to hitchBOT. “HitchBOT I’m so sorry.” And I’m sure that Dana Mitchell and the hundreds of other people like her know that they’re just talking to a robot that does not understand them, and not only because it’s broken.

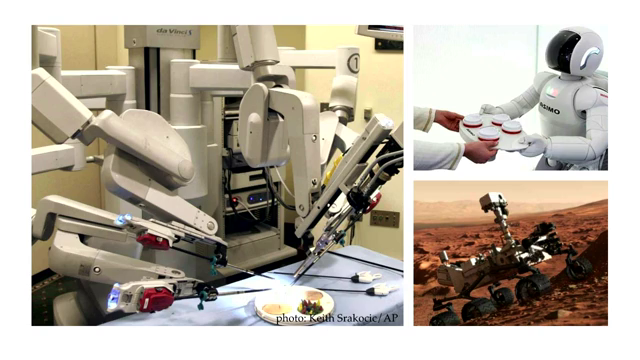

So why are all of these informed adults sympathizing directly with hitchBOT? The answer is anthropomorphism. This is our tendency to project life-like qualities on to other entities and emotionally relate to them through this. And this is why I’m super interested in in the context of robotics. And I think it’s not only interesting but also a really timely subject. It’s timely because robots aren’t anything new. We’ve had robots for years. But the robots have been present kind of behind the scenes in manufacturing and factory contexts, and what’s happening now is that they’re entering into all of these new areas of our lives. Hospitals and transportation systems and the military. And they’re coming into our workplaces and our households.

So what’s really new about robots is that they’re going to be everywhere. And it’s also nothing new that we can emotionally relate to objects. People have always had the tendency to fall in love with cars and gadgets and stuffed animals. But the new thing about robots is what we’re seeing is this effect tends to be more intense. Those of us who work in human-robot interaction, we think that this is because of the interplay of three factors.

The first factor is physicality. People are also able to fall in love with virtual objects. This is the Portal Companion Cube from the video game, that a lot of people are very fond of. But studies are showing that we’re very physical creatures, and we respond very differently to something that’s in our physical space versus something that’s virtual on the screen.

The second factor is movement. Robots move, and we’re biologically hard-wired to anything that’s moving in our physical space in a way that we can’t quite anticipate what it’s going to do next. We’ll automatically project intent onto that movement. You see this even with really simple examples like the Roomba vacuum cleaner. It just moves around randomly on your floor to clean it, and it doesn’t know the difference between you and a chair. But just the fact that it’s moving around causes people to name the Roomba, to feel bad for the Roomba when it gets stuck under the couch. So it starts there, and then there are much more extreme example where there are countless stories of soldiers in the United States military that become emotionally attached to the robots that they’re working with.

They’ll name them, and they’ll give them medals, and when they’re broken and they need to get them repaired they want to have the exact same one back, not a different one. And if they can’t repair them they’ll have funerals for the robots, with gun salutes. There’s even stories—Peter Singer has a book called Wired for War, and there are stories of soldiers actually risking their lives to save the robots that they’re working with. And what’s really interesting here is that these robot aren’t designed to elicit this response at all. They’re just meant to be tools.

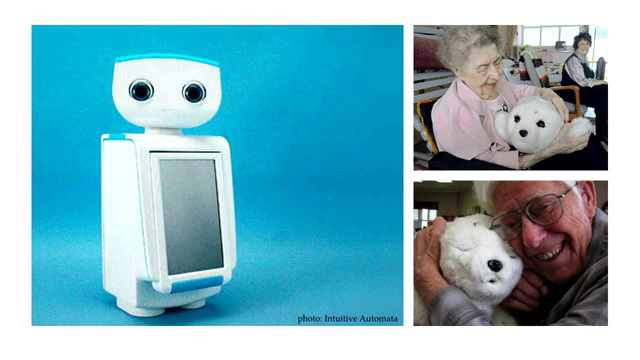

So that brings us to the third factor, which is this whole new category of robots that are specifically designed to make us respond to them in this way. They have faces and eyes, and they’re cute and they mimic all of these sounds and movements that we automatically and subconsciously associate with states of mind. So what we’re seeing is that the effect becomes really strong with these robots, and studies are showing that people really respond to these cues and will respond to them even if we’re perfectly aware that this is just a machine.

If you work in social robotics this is awesome, because it means you can create so much engagement with this technology. And we’re already seeing this put to really great uses in health and education, for example. There’s the Nao next-generation robot that can work with autistic children and effectively bridge the communication between parent and child. We have some cute robots at the MIT Media Lab that teach children reading skills and storytelling and coding skills. And they’re really engaging, because who wouldn’t want to learn languages from a fluffy dragon instead of an adult.

And it’s not just for kids. We have robots motivating adults to do things. There’s a weight-loss coach robot that is more effective than conventional methods because people are engaging with what they perceive to be a social actor. And we have the Paro seal that’s used in elderly care and with dementia patients. It’s kind of brilliant because it gives people the sense of nurturing something instead of just being the ones that are being cared for all of the time. It’s even been used as an alternative to medication, for calming distressed patients.

So that’s kind of cool, and it’s also kind of cool to see that we’re starting to see that we’ll be able to use robots instead of animal therapy in a lot of cases where we can’t use animal therapy, which is quite a few contexts. And the reason it works is because people will treat certain robots more like an animal than a machine or a device. There’s actually this really great example with very simple technology, this recent example from Japan.

Sony used to make this robot dog called the Aibo, and they stopped selling it a while ago. But they just recently pulled the tech support [video skips ~10secs] funerals. So that’s kind of adorable and heartwarming or maybe a little creepy depending on how you feel about it.

And actually I do want to talk about the dark side of this for a little as well. Or, the issues that myself and other people think need to be addressed moving forward. Just to give you an overview of some of the concerns, a lot of these robots are being used with elderly and with children, as I mentioned, and there are some questions of human autonomy and human dignity if you’re deceiving people into treating something like it’s alive when really it isn’t. And then there are some questions of supplementing versus replacing human care. Honestly a lot of the robots that I see being developed are definitely there to supplement human care and not replace it. But we don’t know how this technology’s going to be used down the road, and it’s worth keeping in mind that if we start replacing human care, we don’t know what aspects are going to get lost in that process.

Another big issue is privacy and data security, because you have these robots that will be entering into more intimate areas like our households, and they’ll be collecting personal data in order to function better as social robots, and I do not see the companies working on this technology really caring enough about privacy and data security at the moment.

Another issue is emotional manipulation. If people are emotionally engaging with robots, is it okay for my companion robot to have in-app purchases? Or is it okay for my grandfather’s robot pet to suddenly need a mandatory software upgrade that costs $10,000? This is something that we could decide to let the market regulate, or it might be something that we need consumer protection laws for. It’s a little early for that now, but I think that this is going to become an issue within the next few years, the next decade or so.

And then we have contexts where we don’t want people to anthropomorphize robots, and we don’t really know how to prevent that. So in the military examples, again, it can be anything from inefficient to dangerous for people to be getting emotionally attached to the tools that they’re working with, and we currently don’t really know how to prevent that from happening.

So these are some of the issues that I think we should be thinking about as this moves forward. And I do think we should be addressing these within the recognition that this is incredibly useful technology. And I don’t want to throw the baby out with the bathwater. I think we can talk about privacy and consumer protection and all of the ethical issues without dismissing the potential of the technology.

And in the meantime I also think it’s just a really fascinating area to study, because when we look at this anthropomorphization of robots, we’re actually learning more about human psychology in the process.

I’d like to show a video that some of you may have seen. It got a little bit of attention last February. This is a company called Boston Dynamics. They’re owned by Google, and they make these military robots that are very animal-like, or human-like, and this is a video where they introduce their newest robot, which is named Spot. It looks a little bit like a dog, and what’s going to happen in the video is they’re going to kick it, and then once more a little harder. [Video plays through to ~0:35]

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=M8YjvHYbZ9w

It was interesting when this video came out. Obviously they’re kicking the robot to demonstrate how stable it is. But it does skid around in a very dog-like way, and so a lot of people expressed very negative emotions about this video. They took to Twitter and online comments to say that this was disturbing. And it got to the point where PETA, the animal rights organization, was getting so many phone calls that they had to issue a press statement, and they said basically “we’re not going to lose any sleep over this ‘cuz it’s not a real dog.” But they do say it makes sense that people find the idea of this violence inappropriate.

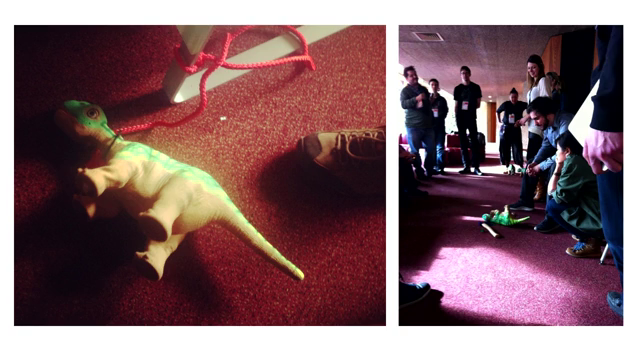

Now, violence and empathy in robotics is my main interest, and I’ve been working on this for quite some time. I’ve been interested in it for years now. A few years ago my friend Hannes Gassert and I did a workshop at the Lift conference in Geneva. We took these Pleo dinosaur robots. This is a $500 toy. It’s really cute. They respond when you touch them, and if you hold them up by the tail, they cry and they get really upset and you have to put them down and calm them down. So we gave these robots to groups of people and had them name them and play with them. I think we had five of them. And then we asked them to torture and kill them.

We thought it would be interesting or funny. It actually turned out to be more dramatic than we expected. People really refused to even strike the Pleos, and we had to kind of play mind games with them and force them to get a little more brutal. In the end only one of the Pleos died. Four of them are still living happily somewhere. But I came away from this workshop feeling that this was super interesting. But also feeling that I didn’t learn enough from the workshop because it’s not a controlled setting, and it wasn’t an experiment. You can’t tell are people hesitating because it costs $500, or are they hesitating out of empathy, and there’s a lot of social dynamics. So I went back to the lab, and since then I’ve been working with cheaper robots, because you can’t use $500 robots if they’re going to get smashed.

I’ve been working with a research partner named Palash Nandy. We’ve been using these HEXBUGs. They’re just this toy that you can buy and they move around like little insects. So we have people come into the lab and smash them with mallets. We’ve been interested in a few different factors, but one of the things that we first tested was how do people respond if you personify the robot? If you say, “This is Frank. And Frank’s favorite color is red, and he likes to play.” And then will people hesitate more to smash Frank?

But the other thing we were interested in was the relationship between people’s natural tendency for empathy, and how they would respond to the robot. So we did psychological empathy testing with people, and we found that people with low empathic concern for others, they didn’t care about Frank. They would just smash Frank. And people with high empathic concern, they responded really strongly to the personification and the storytelling. And it’s kind of cool because what we’ve come up with is a version of the Voight-Kampff test from Blade Runner. I don’t know if you guys know this concept. How many of you have seen Blade Runner or read the book? [Most of visible audience raises hands] Wow. That is a lot of people.

Okay, for those of you who have not, you should. It’s a total classic. And I won’t spoil anything. But as many of you know it takes place in a world where robots and humans look exactly the same so they develop this test to distinguish between them where they use storytelling and they measure people’s empathic responses to tell whether you’re a human or a robot. So what we’ve done is like a mashup of that where we can tell whether you’re an empathic human or not depending on how you respond to storytelling around robots.

So that’s kind of cool. It’s actually not the question that I’m most interested in answering. The question that I’m most interested in is not can we measure people’s empathy with robots, but can we change people’s empathy with robots? So for example, if you’re the guy whose just it is to just kick the dog-like robot all day, could that possibly desensitize you to kicking an actual dog? And then there’s the more positive flipside, which is might we be able to use robots to encourage people to be more empathic? Could we work with children and prisoners or anyone, really, and kind of encourage empathy in people with robots?

So those are questions I’m interested in. I’m generally interested in all of the questions that I’ve raised here today, and I think that they encompass kind of the core of what I view as robot ethics. (And I should say I love robots, probably more than anyone else.) But I don’t think that robot ethics is actually about robots. I think that it’s about humans. I think that it’s about our relationship with robots, but mainly robot ethics is about our relationship with each other.

Thank you.

Further Reference

Description at The Conference’s site of the session this talk was part of, and Kate’s speaker bio.

Kate previously spoke to CBC’s Spark program about her research, including more detail on the Pleo experiment. There’s also an extended interview.