Zarah Rahman: I’ll be talking about the importance of building bridges between researchers who are thinking critically about technology and data, and civil society. So those working for positive social change.

So I came to this fellowship wanting to explore the idea of tech translation, which is a term that a colleague and friend of mine Lucy Chambers coined a couple of years ago. I was using it very specifically to explain this observation I kept seeing that people who are working in technology who had a really deep understanding of technology were effectively speaking almost a different language to those outside of the tech sector.

I spent sometime in 2015 collecting a series of case studies around how civil society organizations… The challenges that they were facing when they were trying to engage with technology and data. And these ranged from not knowing how to manage data that they were collecting about vulnerable communities, to using resources to build an app that ended up to be kind of useless.

So, some context. I work for a nonprofit organization called The Engine Room. Our mission is to support civil society to use technology and data and more effectively and strategically in their work. And when I say civil society I mean journalists, media activists, community organizers, nonprofit organizations. Some context about the situations in which we’re working, it’s often very resource-limited. There’s not that much money. There’s a lot of pressure. And as you can imagine right now, it feels like the problems that we’re trying to address are growing even bigger.

And over the past couple of years, it feels like civil society has been almost overwhelmed with promises of how technology can suddenly magically solve the problems that we’re trying to address. Some coming from tech giants who say they’ve developed some semblance of social conscience suddenly. Some from startups who see a problem and think that technology can help without thinking about the systemic issues underlying it. And they come with money, and resources, and expertise.

Compare that to the attitudes that we have here. So we are a group of people at Data & Society, and academics and researchers who are thinking deeply, critically about the role that technology and data is having in the world. Groups of academics from all sorts of disciplines are building up an ever-growing body of research around the social implications of technology. And we’re not alone. We’re learning from each other and the world around us, and we have the opportunity to spread our ideas.

Ursula K. LeGuin wrote in her book The Dispossessed, “The idea is like grass. It craves light, likes crowds, thrives on crossbreeding, and grows better for being stepped on.” The concept of ideas improving with better diversity of people contributing is not new. So then my question becomes, in terms of tech criticism, who is contributing? As far as I can tell, by and large it’s not often activists or people working for positive social change explicitly.

One potential explanation is written about in this post by Chris Olah and Shan Carter from Google Brain. They write about the idea of “research debt,” essentially the labor that a researcher needs to do in order to start contributing to a field. They need to first understand what’s come before, climb this mountain of previous work. Then when they can contribute, they contribute by putting their work on top of this mountain. Which makes the mountain higher for those who come after, and it makes it harder to climb. They use the term “debt” here to reflect that in the short term though this might seem like a logical way to go about it, in the long term it’s not necessarily that logical or progressive or useful, really. Like technical debt for programmers, it’s again a practice that seems logical in the short term but might be problematic in the long term.

I observed this debt a lot in the tech and social change space. Here, as I said there are academics and researchers who are thinking deeply and critically about technology and data. In many civil society organizations there are people implementing tech projects, working with existing platforms, who have no idea about the critiques that exist. And it’s not that the people in those spaces aren’t critical thinkers. Everyone working in social justice work or for social change, it’s all about analyzing power and understanding people and politics and relationships. It’s often almost the same kind of set of skills, but there’s a complete lack of exchange between these different spaces. I think this is problematic for a number of reasons. I’m just going to go into two of them here.

Firstly, and this won’t be new to many of you, the negative effects of technology are often first felt by those on the margins of society. This has been true throughout history of colonialism, medical technologies, warfare technologies, anything. So as a result it’s crucial that those working with marginalized communities, or those members of those communities, have the tools they need to be able to critically assess technologies.

One of the earliest uses of biometric technologies for identification was on Afghan refugees back in 2002. That’s fifteen years ago. They were crossing the Afghanistan/Pakistan border, and it was by a UN refugee agency, done in partnership with a tech company who was selling them this wonderful product that was going to solve all their problems. Very little attention was paid at the time to the privacy rights of the refugees in question. The technologies were used on 4.2 million people across a period of five years. Before being used on those 5.2 million people it had been tested on 300 people.

From research carried out by a Katja Jacobsen in 2010, there were many problems, as you can imagine. She documented them in a really nice research paper. This is just one quote from someone who ended up using and having to implement these technologies, saying, “Previously, you could doubt your own judgment,” before the machines, “this iris recognition will make it much better. How can they argue now, the machine can’t make a mistake.”

That initiative was probably, I have to imagine, implemented by people with the very best of intentions. They were working in the humanitarian sector. They probably went into the sector wanting to make people’s lives better. To my mind it’s really clear that they were lacking, and often still are, a critical lens to view the technologies that they’re being sold on and asked to use. Without tools to critically assess and think about the role of technology in society, I worry that civil society will end up perpetuating inequality rather than dismantling the power structures we seek to dismantle.

The second reason I find this lack of exchange kind of problematic is that it’s far easier to poke holes and find problems with projects and ideas and technologies than it is to build them. Sarah Watson talks about an evolution of tech criticism that she calls “constructive tech criticism.” In her words, it goes beyond intellectual arguments. It is embodied, practical, and accessible, and it offers frameworks for living with technology.

That’s exactly what people working in civil society and for positive social change are trying to do. We’re engaging with the problems of society. We’re trying to build better futures and not just suggest alternative possibilities, but build them and make them happen. This is a massive challenge, obviously, that needs a diverse set of people and skills and perspectives in addition to activists and practitioners and organizers. It needs constructive tech critics, too.

So, how can we create these spaces for engagement? This would mean creating spaces for people from diverse backgrounds and experience to contribute to research meaningfully. Not just being interviewees or participants in a research project, but being the people who design the project or carry out the research. But going back to what I said earlier about research debt, that path of engagement currently exists primarily by asking people who already carry a heavy burden to climb mountains rather than walk along bridges.

When people working in civil society or people that I work with ask me, “What should I read or what should I look at to try and understand these critical perspectives you talk about?” I often actually don’t know what to suggest. I know that they have resource limitations, time pressure, it needs to be accessible. And I’m not really sure where those bridges are.

https://twitter.com/zararah/status/846525385374420992

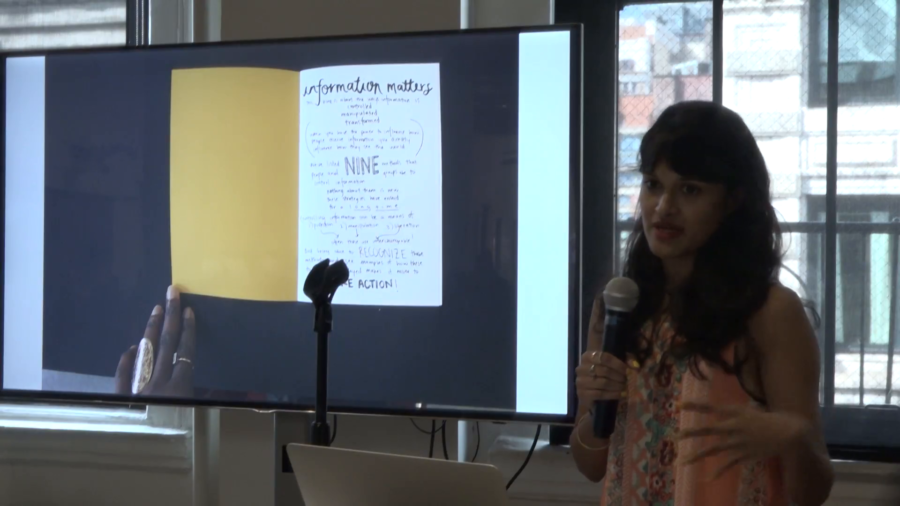

So in response to this, and in response to seeing how quickly misinformation spread in 2016, I’ve been thinking a lot about different ways to communicate these ideas, not just in a way that tries to explain them as though I’m an expert at explaining things to lay people, but in a way that encourages interrogation and encourages engagement, and allows people to actually question what I’m saying. Together with my collaborative Mimi, who’s in the back, we developed this zine as a playful way of helping people think critically about the role of information in society.

We wanted it to be familiar. It’s a physical artifact. We wanted people to look at it and not think that we’re experts telling them things, but think, “Hey, I could have probably done this myself, too.” So it’s hand-written. We wanted to give context as to why this should matter, so each page has a historical example that speaks to the context of the people that are reading it. So we’ve translated it into German and replaced the examples with German examples, and we’re doing the same for Spanish.

We want to keep exploring this idea so we’ve set up studio, Small Format, where for now at least, you can buy the German and English versions of the zine, and we’ll be using Small Format to continue to explore playful and critical printed interventions for exploring data. So watch this space.

In conclusion, I believe that the role of distilling complex ideas into their simplest forms is a task that the tech critic community could get a lot better at. We need to be able to explain complexity in simple ideas, and explain ideas not by relying on knowledge of Western philosophers or theorists but by situating it within local context and lived experience.

Last week at a conference that Ingrid hosted called Future Perfect, Ruha Benjamin talked about the value of creating knowledge not to convince people who we want to impress or persuade of a certain thing, but for ourselves and for people who need it. I’d ask you all to think carefully about who you’re producing your knowledge for and whether they’re the ones that could benefit the most from it. Thank you.