Well, it’s an enormous pleasure to be here and I’m really honored to follow Ada Colau. I’m a great admirer of the project. I want to talk a bit about what is a city. I think up till quite recently you could say that if it was very densely built, it was a city. Let me posit that today, a lot of density is actually deurbanizing the city. Think of megaprojects that take over urban tissue—little streets, little squares, little old buildings. Places that long-term residents felt this was their place. When that happens, when that inserts itself into a city, no matter how it adds to the density, I would argue it deurbanizes.

And so what I want to talk about (and I have clearly very little time but there’s a very long text for those of you are interested), I want to talk about investments that are happening in property. So let me just move straight into it. I’m working with a data set of the top hundred cities that are the object of desire, if you want, of investors. A lot of this investment—what I’m talking about, minimum price to give you a sense, an idea—is five million in the case of New York. The value is going to change in other places. Mostly what I’m focusing on here is either corporate buildings or very luxury apartments.

Now, for me a city, just as background, is a complex but incomplete system. And in that mixity of complexity and incompleteness lies the capacity of cities to have very long lives. Much longer lives than very powerful corporations, which often are very closed systems. So if you think of a city like London— I don’t know about Venice. I would not dare to talk about Venice, being here in Venice. But if you think of New York City, if you think of London, those are cities where most of the very powerful corporations that once existed (I emphasize: most, not all) no longer exist. But the city of London, I mean the larger city, exists. And so do the neighborhoods.

And the neighborhoods are modest places. They have outlived very powerful actors. So it tells you something about the city. It cannot be reduced to simply a set of corporate sectors.

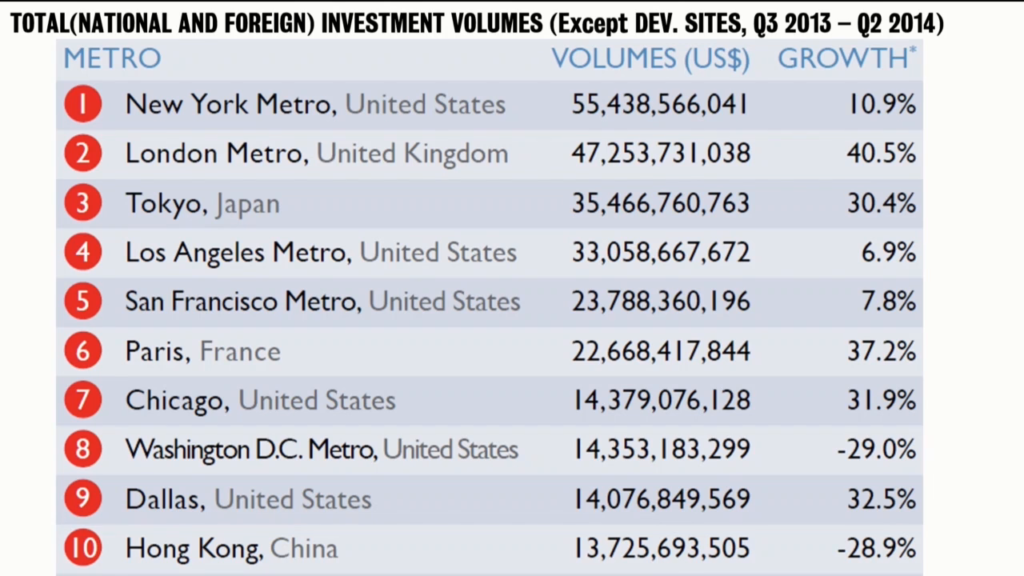

Now, here are some figures on investment. This is just acquiring property. This is not about developing. And the full list is a hundred. And I also just got the data for the last year. This is one year, 2013 to 2014. And you can see that New York Metro region is at the top, fifty-five billion. This is just one year. This is a process that really takes off after to 2008, the crisis, but really becomes very very strong in the last few years. London Metro, number two, etc., etc. Paris, number six. Most people in Paris, by the way, are barely aware that this is happening. I’m looking forward to Missika’s talk here.

Now, this is another way of distributing. So, when you look at the top hundred cities, at the end it is a very sort of small share. And as you can see there, Miami is at the bottom of this. But this again I repeat: this is a list of a hundred.

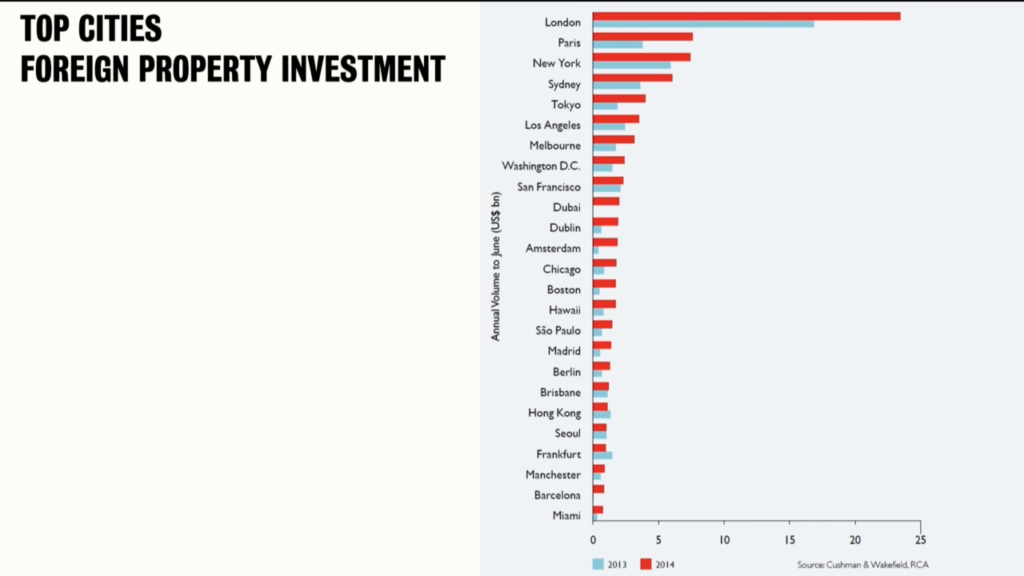

So this is foreign property. I wanted to emphasize that if you look at foreign investment… In other words not national but all kinds of foreign, then London is number one. And what is quite interesting is, if you want, the invisibility of it. So I like to point out what does this is all look like?

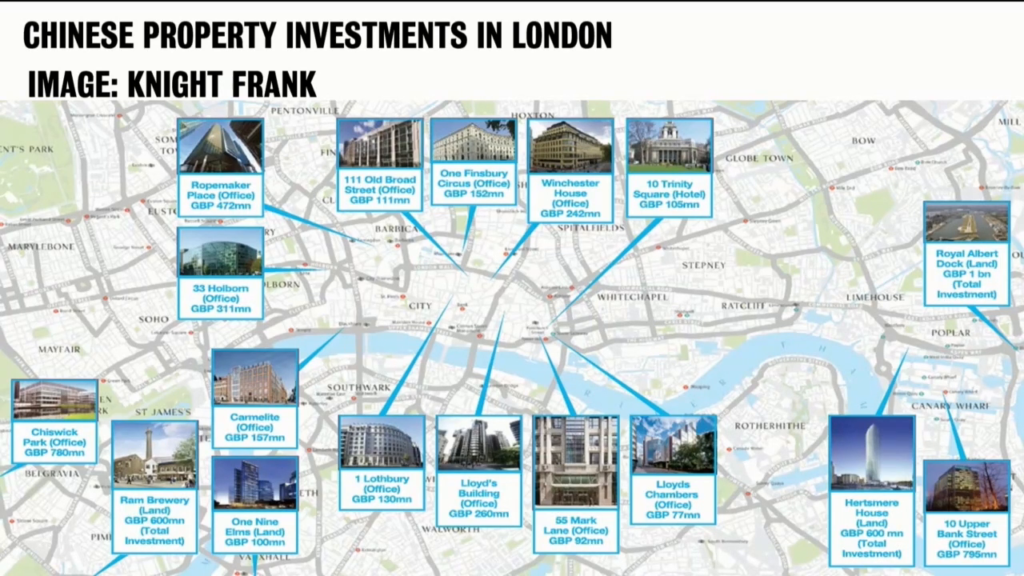

And here is one case. This is one Chinese company that owns all of these buildings. They’re mostly landmarked. Nothing can be changed, at least for a while. And I think, very good taste, by the way, this company. These are very very nice. I don’t particularly like that one over there. And that is probably not a landmark building.

But the point here is this is not just about buying and tearing down. When you hear people walking by, their tours— I did did a long walk with somebody from Die Zeit who was writing a story about all of this, and you heard the tourists literally say, “Look at these wonderful British buildings.” Of course they’re British buildings, you know British history. But they’re all owned by one Chinese company.

So there is a second issue here that I want to point out, which is that in all its materiality, this is a kind of invisible project. You know, you don’t know that it is foreign-owned. Now, I do think that the fact that it is foreign-owned matters that much. My main concern is this big capacity that corporations have to buy a whole set of buildings. I don’t know exactly where that goes, but that privatizes. And that’s sort of destroys some of this notion of the incompleteness of cities.

Now, this is another case. This is actually site development. This is also a foreign company that has bought a very big piece of land in New York. And that I would say is not good taste. They are building fourteen of these huge towers. That again raises the density, but actually deurbanizes that space.

Now if you look at all of these figures when it comes to the stop one hundred cities, they represent 10% of the world’s population, 30% of the world’s GDP, and 76% of property investment.

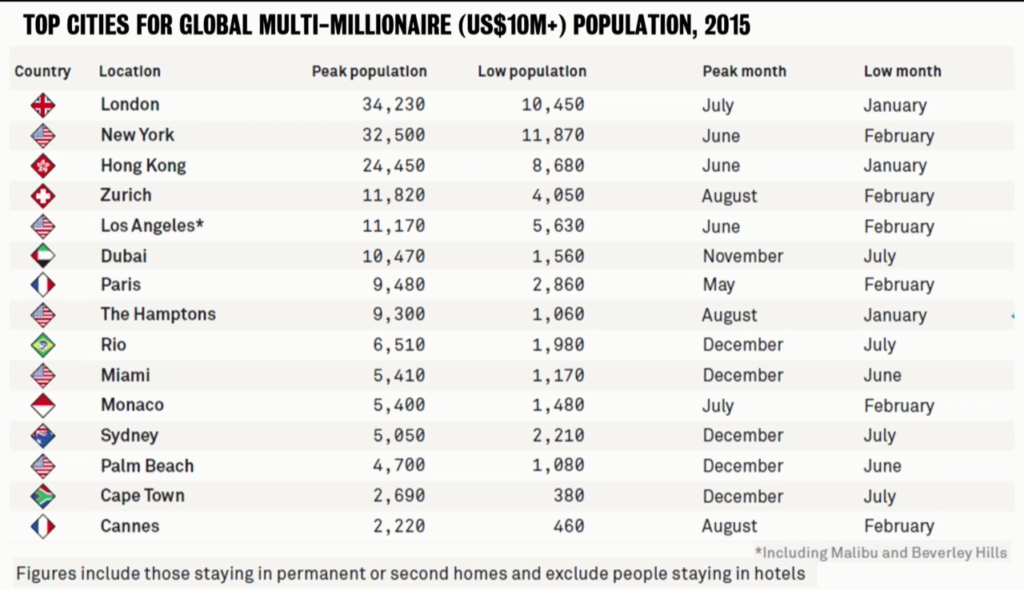

If we wanted to enter let’s say the gossip columns— This data actually exists. I didn’t gather this. And you can see these are the global multimillionaires, etc. and here are all the cities. It includes Capetown, Palm Beach, Sydney, etc. This is not of particular interest to me, but what is interesting is the amount of buying that is happening. And that to me, coming back to this definition of the city as complex but incomplete, I find a little disturbing.

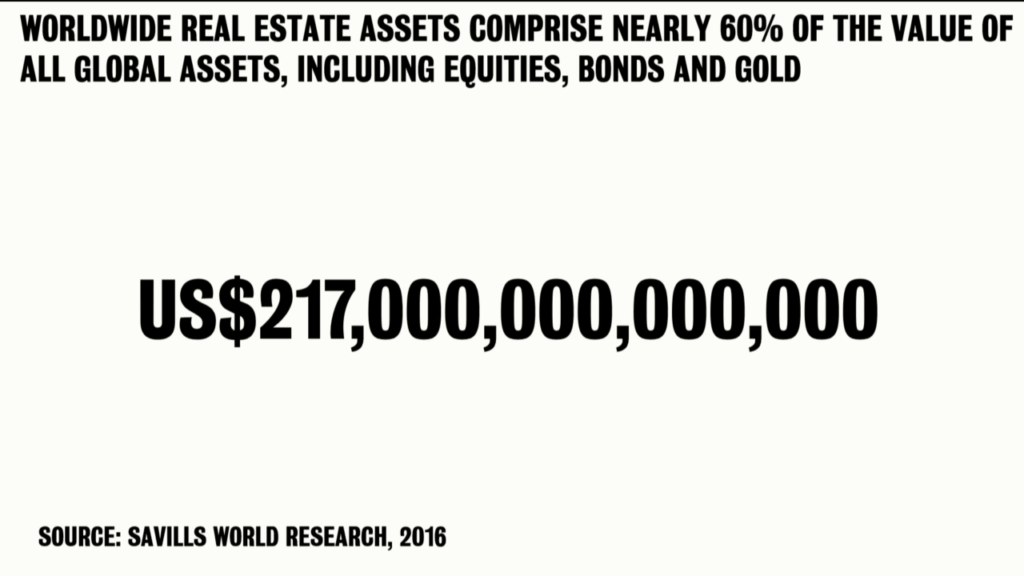

The total value, the worldwide real estate assets— Now when you talk that language (real estate assets) it means that there’s a bit of financializing that has happened, right? It can circulate globally as a value. It’s $217 trillion. That’s a lot of zeroes. I know that this language translates very very differently in different languages, but you can see it’s quite a bit.

Now, just to put this in perspective, if you look at the value of finance, just as a juxtaposition, where the typical measure is outstanding derivatives, that is in the quadrillions. So finance is way ahead. But if you look at something like global GDP of all the countries in the world, then you are back to the trillions, you know. Like $800 trillion. So this is quite a bit. I give you these other figures so that you understand what it is.

So, this is another way of looking at what this all looked like. And this is London property purchased by overseas companies from 2005 to 2014. And you can see it’s a lot. London is a key destination, you know. I think its history of empire is also contributing to this. You know, history sort of catches up.

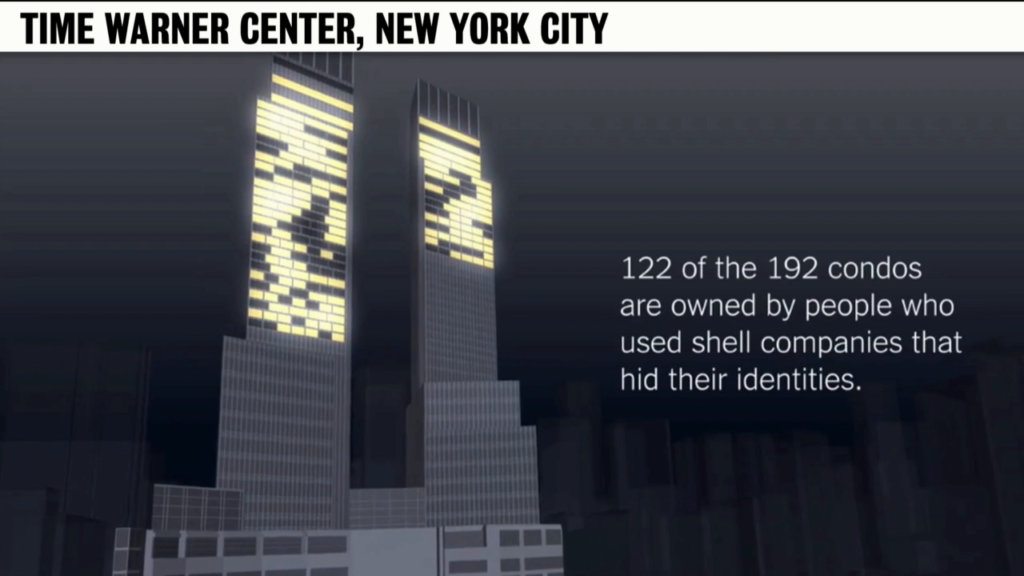

And here we go to Manhattan. And one thing that is very important in Manhattan in this whole bit of buying are shell companies. So I just want to run you very quickly through some figures that have to do with that. So here you have that in 2014, 54% of sales over $5 million in Manhattan were to shell companies. Shell companies are fictitious companies. They really… This is sort of something that’s an instrument to buy, in this case.

Now come two or three very famous, fancy, much-admired, blahblah, buildings. (Not admired by everybody, by the way. But still, admired.) Time Warner Center. A hundred and twenty-two of the 192 condos are owned by people who use shell companies that hid their identities. So you get a picture.

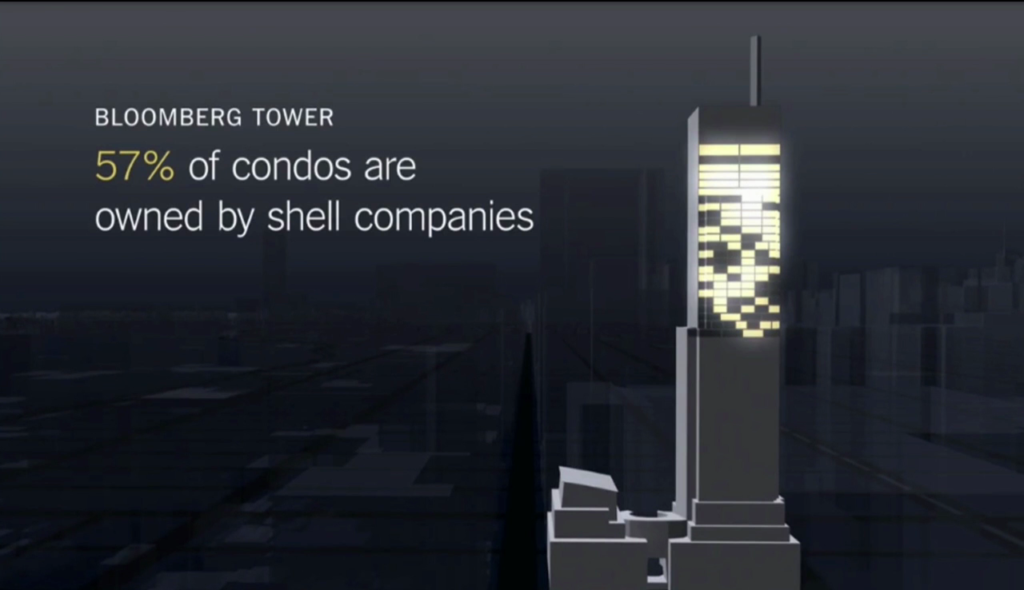

Here is another famous building in Manhattan, Bloomberg Tower. Fifty-seven percent of comdos are owned by shell companies. And that is why so many of these buildings at night are dark. You don’t see life in there, really.

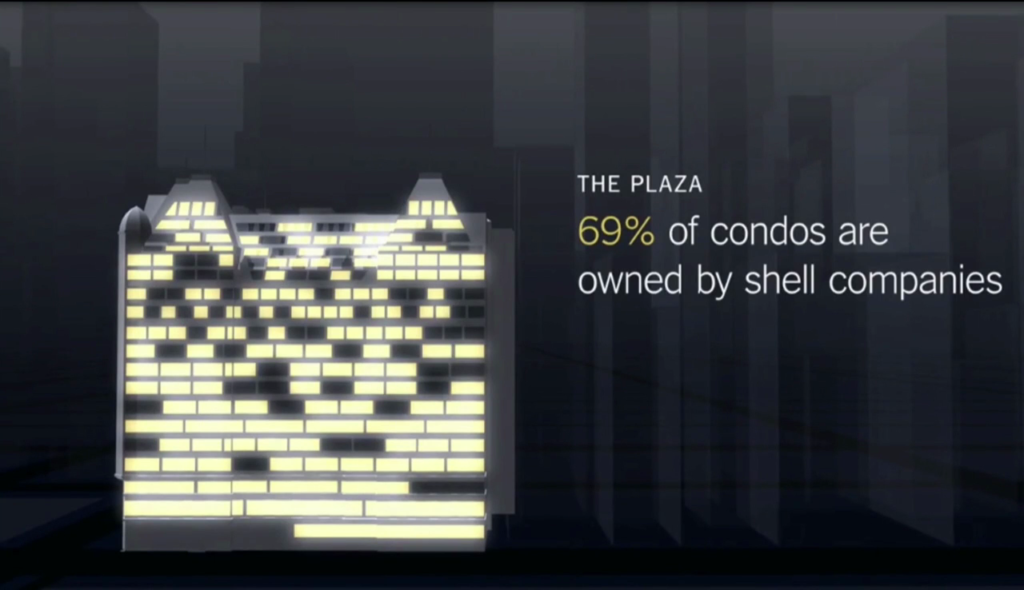

And this is The Plaza. Sixty-nine percent of condos are owned by shell— And so it goes on and on.

Now, that’s not all that is happening in this domain that is concerning me—that worries me a bit. One is the inventing of new housing markets. Which is really a kind of matching market. Which is used by universities if they want to hire specialized people. They go to only some other universities to recruit. But this is a very interesting application of that concept.

So here you have one of these matching markets. And the list goes on. I just have a few here. And the key feature is minimum prices. So, in the case of Monaco, and the main nationalities. What you see here are the main nationalities, and the prices.

In the case of Monaco, $18.9 million, etc. The Financial Times prepared this a few years ago. So there you see it goes on and on. Very interesting to me is that in Shanghai, if you see, the world is buying. Hong Kong, it’s mostly mainland Chinese who are buying. These are the main nationalities, not the only ones. And Dubai has a very international structure that is quite different from others.

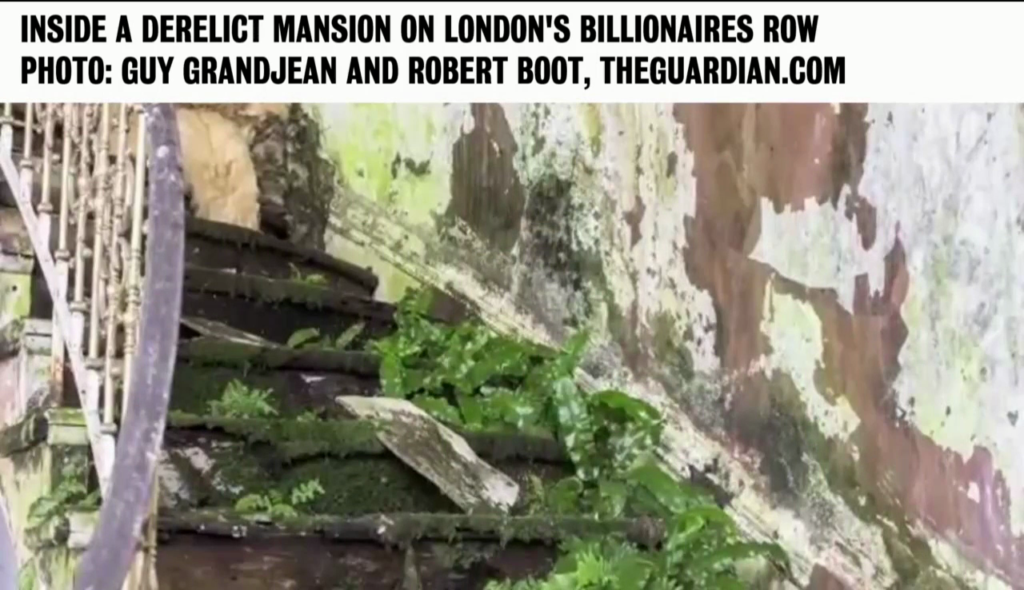

Now, a Guardian photographer got access to some of these properties, and I’m just showing you two images. Some of these properties—this is London—have not been inhabited for years.

Here’s another one. It takes quite a bit of time for that much moss to grow.

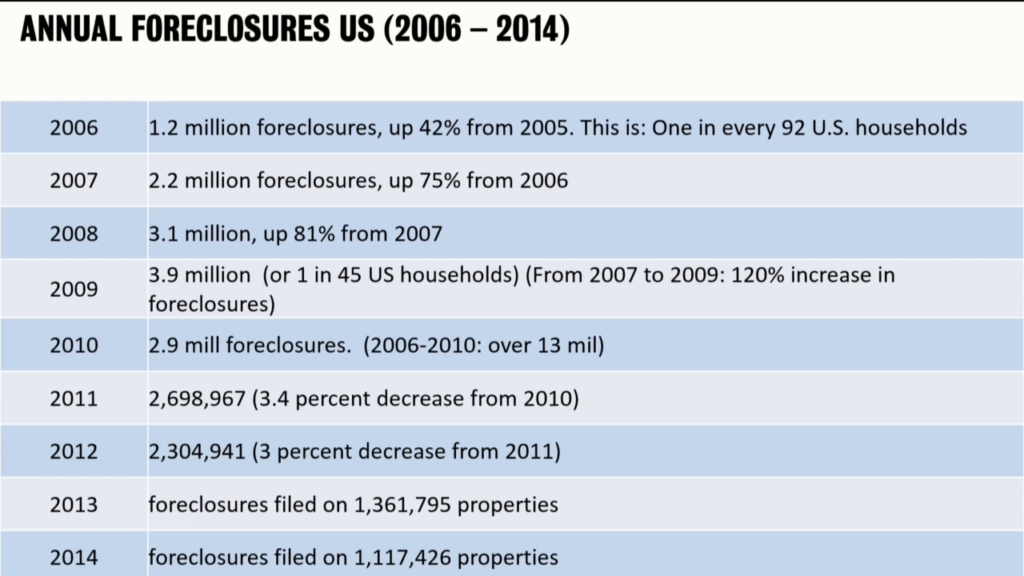

Now, juxtaposing (and again this the case of the United States), we have millions of households that have been thrown out of their homes. Which also generates more empty urban space. This is a list of foreclosures. The data come from the central bank. When Bernanke, the head of the Fed in New York— When he stepped down, he made a big speech about all the good things. And then he said two things that were intractable. One concerned finance. Dark pools in finance; I won’t talk about that. The other one concerned this.

He said and by the end of 2014… It’s always 2014 that comes up, so don’t get too confused. So, by the end of 2014, he said, fourteen million households will have lost their homes. So, this is a very serious kind of situation.

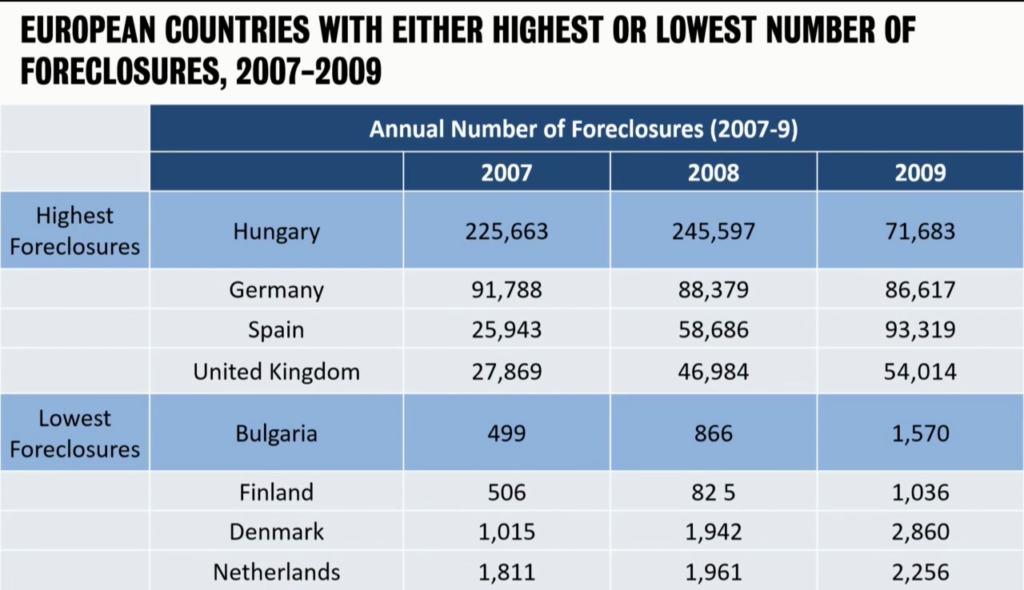

It’s happening in Europe, too. Germany, over a million— The list goes on after 2009, over a million households. A household can be one, two, three people. In the case of the United States we’re talking about millions, thirty million minimum. And again, in its materiality, this is an invisible story.

So why does this all matter? And here I want to come back to this notion of the city. So I started out saying the city’s a complex but incomplete system. If you have massive projects, massive densities, you are losing urbanity. You are losing cityness. You’re adding density which, you know, for some is enough to have a city. But there is more. In a way, the large cities especially are one of the few places where those without power get to make a history. They get to make a culture. They get to make an economy.

They are also today’s frontier zone, I think. I think of a frontier zone as a zone where actors from very different worlds can have an encounter. If you think of low-wage workers, or low-income families, it’s in cities where they actually can have an encounter with power, with wealth, etc. And out of that comes learning. Out of that can come oppositionality. And I think that we need to protect the cityness of cities. And I think, as I said already, more and more build[ing] stuff is not necessarily city. It’s not necessarily urban.

And one property, one capacity that cities have is that— And it’s very partial, it’s very momentary. That at various times of the day, the city reduces us all, or makes us all (in a more positive sense) urban subjects. Not religious, not class, not ethnic. No, urban. And these are very precious moments of the day. But they enable that. There are very few spaces that allow that.

Now, if you think of large, complex, corporate setups, that does not enable that. The poor, the low-income worker, can go in there and clean. But when he’s done, he goes out. In the city, on the other hand, you have a lot of neighborhoods that are poor, where real lives can take place. Where local economies are made. Where little local cultures can thrive. So in that sense, the history that we are witnessing, that is happening, I think is very disturbing to me.

I want to juxtapose to that the fact of land grabs in the Global South. When you take the broader map of the buying up of what once may have been a mix of public and private and it all becomes private, both in rural areas and in urban areas, you begin to think about a larger category that has to do with life space. How do we secure futures that enable many many people to keep on living in cities that are real cities? Thank you very much.

Further Reference

Urban Age: Shaping Cities, La Biennale di Venezia, 2016 web site