Kai Bosworth: …the panel that we have put together today, which is called Liberatory Ecotechnologies, Cyborg Ecologies and the Green New Deal. And unfortunately we’ve had some technical difficulties connecting the audio for Holly Jean Buck and so unfortunately given time constraints and everything it’ll just have to be a slightly-abbreviated panel with the three of us. That said, I’m still thrilled to be bringing together some really interesting and compelling folks who’re working through questions of technology and infrastructure as they relate to the question of a Green New Deal.

So I had a longer spiel as way of introduction but I’m just gonna bypass that and just say quite briefly that our intention in organizing this panel was to get out of the kind of strict binary between technology yes versus technology no, which is a bit of a fallacy we think and instead to begin to think about what are the kinds of provisional ways in which different groups of people can come together collectively to make decisions about our common future. And that’s really what we hopefully talk about when we mean democracy. Although that word I’m not so fond of these days. But if we do want to build a socially just, perhaps ecosocialist or communist future as part of a Green New Deal it will have to actually involve people coming together and making decisions about the forms of technologies, and the relationships between technologies and social formations that may exist.

So, just to talk very briefly about who’s going to be on the panel, then. So I’ll give my own spiel. I’m not going to spend too much time introducing myself just to say that my name is Kai Bosworth. I’m a professor of International Studies at the School of World Studies at Virginia Commonwealth University. And then following me will be Sasha Costanza-Chock, and then Sophie Lewis. And each of us are going to present some interesting and hopefully provocative thoughts on the role of technology and how we should think about technology in a Green New Deal, and then we’ll have some time for discussion and questions at the end. I’ve suggested to our panelists that ten minutes will be the amount of time that we’ll spend talking, so this will go by like that. So, without further ado, then, I’ll continue my own talk.

So, the way in which technology and infrastructure in particular has figured in how Americans have imagined the world has primarily been in a sort of modernist lens, right. And by that I simply mean that technology seems to really embody Enlightenment principles and materialize them. We think of innovation and progress often as driving history. And technological objects like the famous even renewable energy systems like dams seem to fit into our understanding of the sublime experience, not only of nature but of our own intellect, and one in which we are almost side-players to the sort of evolution of technological forms.

David Nye has called this American Technological Sublime, more recently Brian Larkin in an oft-cited and read work has called it “the unbearable modernity of infrastructure.”

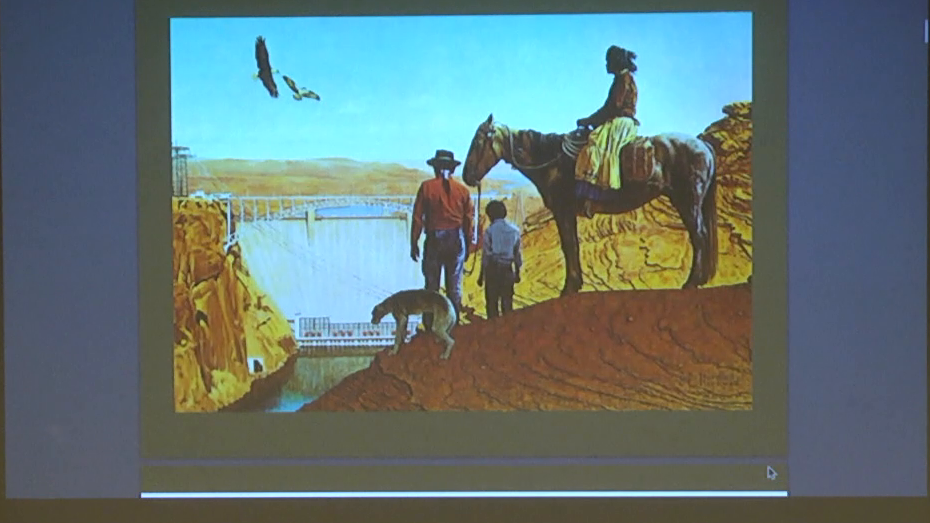

And we can see this in a number of different aesthetic forms as well, as in this Norman Rockwell painting, of course, the unbearable modernity of technology has a flipside in its coloniality, wherein indigenous peoples are figured as somehow on a different developmental path, teleologically, and can only be seen to be receding in the wake of technological forms.

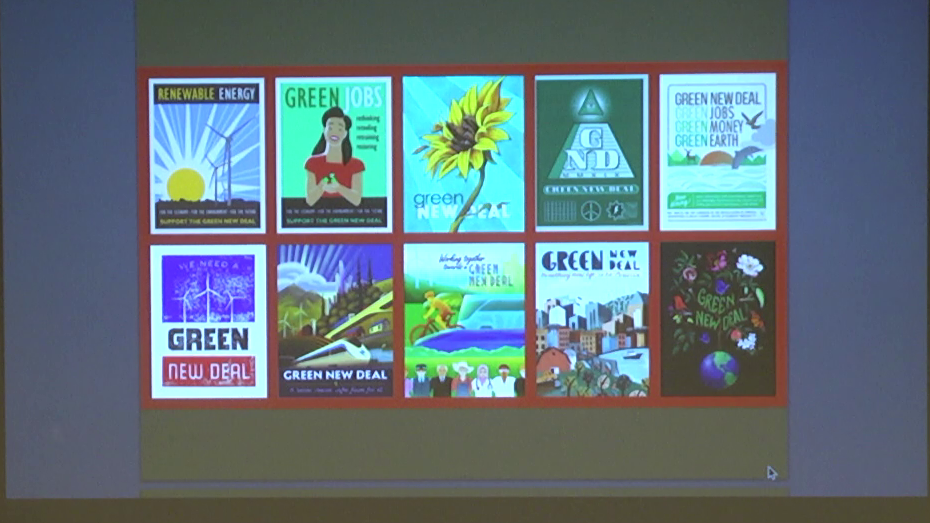

Of course critics of the Green New Deal have also pointed out the manner in which in a kind of classic commodity fetish sort of form, renewable energy hides behind it a whole series of possible forms of exploitation of human and non-human nature. And I think that a lot of critics of the Green New Deal have latched on to this particular narrative of critique of of the sort of modernity of the solutions that are proposed here, especially in its aesthetic form. So I think Malcolm Harris has kind of the classic version of this, in which visualizations of the Green New Deal basically just look like Windows 95 background with solar panels and wind turbines.

And so, we might test whether the artistic representations actually uphold this. I don’t think they do. But really when we imagine you know, wind turbines and landscape oftentimes we do fall back into these [honorizing?] guises.

So my question today, and my provocation, is really whether this modern infrastructural ideal, as Kathryn Furlong calls it, can actually be upheld or seen in actual renewable energy projects and in the kinds of projects that we would hope would be part of a just transition towards a climate future rather than climate apocalypse.

Now, part of the argument from Furlong and others is that really this modern infrastructural ideal is a self-fulfilling prophecy. When you actually look at infrastructure systems from the perspective of the Global South, they’re much more hybrid, precarious, amenable to political and social transformation. And I want to maybe flip this and say hey, if we actually look at the infrastructure systems of renewable energies in North America this might also be the case. That renewable energy might actually figure into certain kinds of decolonial and energy sovereign futures for parts of this part of the world.

And so, I just have three really short provocations about what I’m calling technologies of liberation and existence, and two really quick examples. And then I’ll give way to our other panelists.

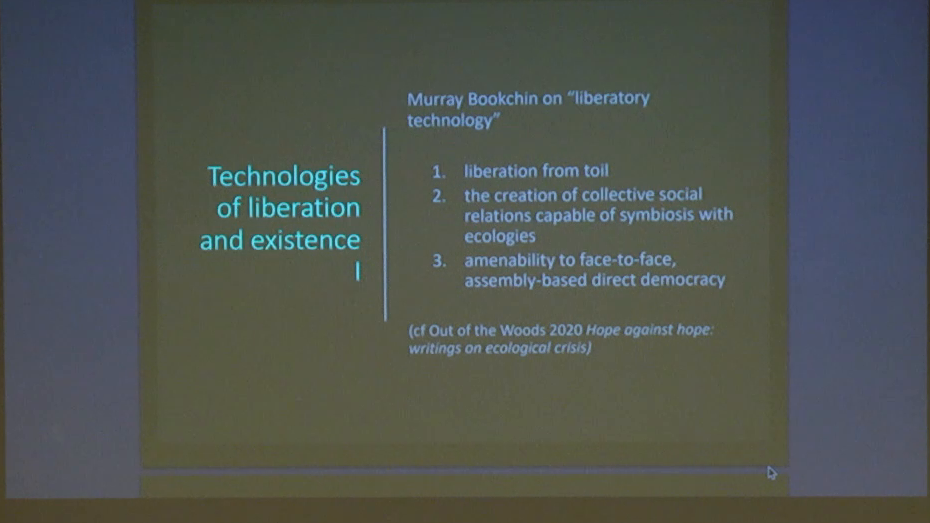

So, first of all there’s this idea where we took the term “liberation technology” really from Murray Bookchin function. And Bookchin is really thinking about the ways in which technologies can contribute not only to liberation from necessity but also from toil, from overwork. But importantly, what often gets lost in discussions of automation and technological change in this sort of framework is also that there are technologies for making decisions about technologies. And these include the creation of collective social relations that can embody in a sort of face-to-face or direct manner how we think about or how we may come to think about what worlds we want to inhabit.

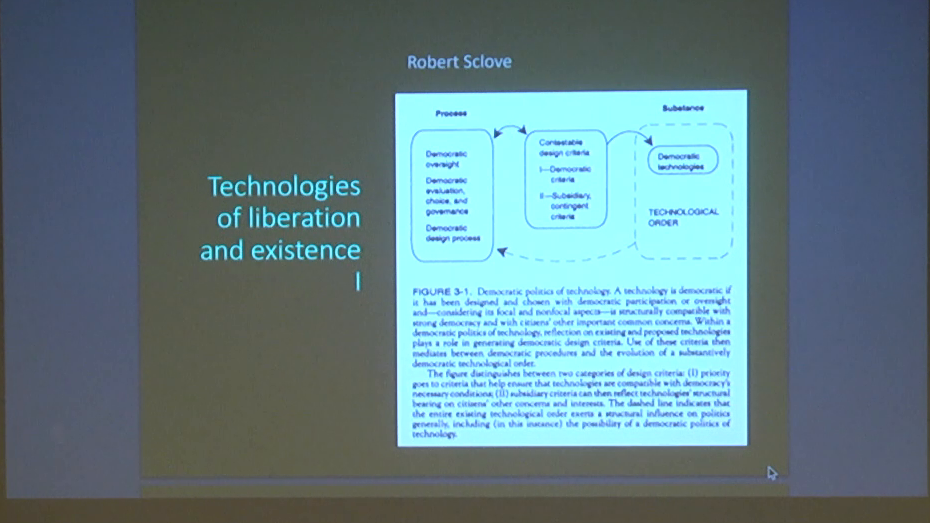

And so following on from Bookchin then, I thinking about someone called Robert Sclove and really a whole series of ridiculous diagrams that I would like to talk about with someone. But I’ll forgo that for a second.

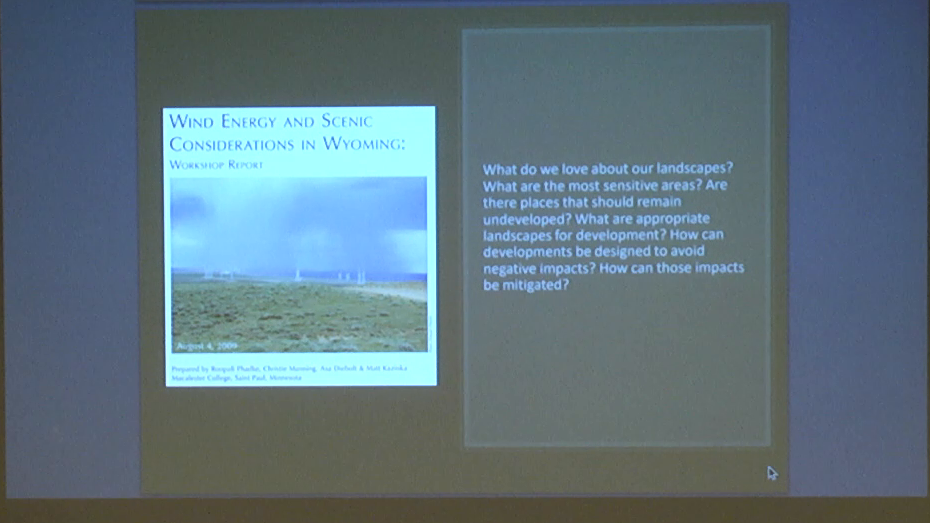

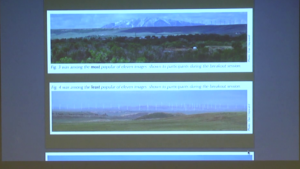

And so one sort of way in which a project I’ve been involved in, or was involved in as a sort of baby social scientist in 2009 was looking at wind energy and scenic considerations in various parts of the United States. There’s actually a lot of opposition in rural America to wind energy. And we were trying to think about hey, what kinds of designs for democracy might we tinker with or experiment with to see if people could create better or more amenable relationships with this new technology that was springing up in places like Wyoming, Minnesota, Wisconsin, and Massachusetts.

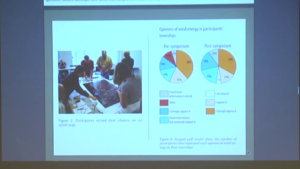

So we ran these design kind of seminars or workshops which brought together different folks in the industry, citizens, in institutions to is sort of collectively think about what kinds of energy systems they would like to see, and what kinds of landscapes they value, and how the mitigation of the effects of these energy systems might be achieved.

So we looked at images, and thinking about various kinds of speculative forms. What kinds of versions people like or don’t like. And also the terms that they would use to describe the landscapes. So the aesthetic terms that might be connected to those values.

And what’s interesting then is this is not just democracy as a gauge of one’s pre-existing interests, but also it transforms people, right. And hopefully it transforms them in a way where it’s demystifying, where they can break through that sort of commodity fetish ideological version. But in fact we’re also discovering that in other cases people become more amenable to wind energy, generally, but more opposed to it after doing a workshop on it in their local community. That their values are sort of reinforced. So, one example of how one can think about infrastructure development not in a sort of overwhelming modernizing sort of guise.

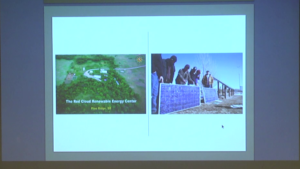

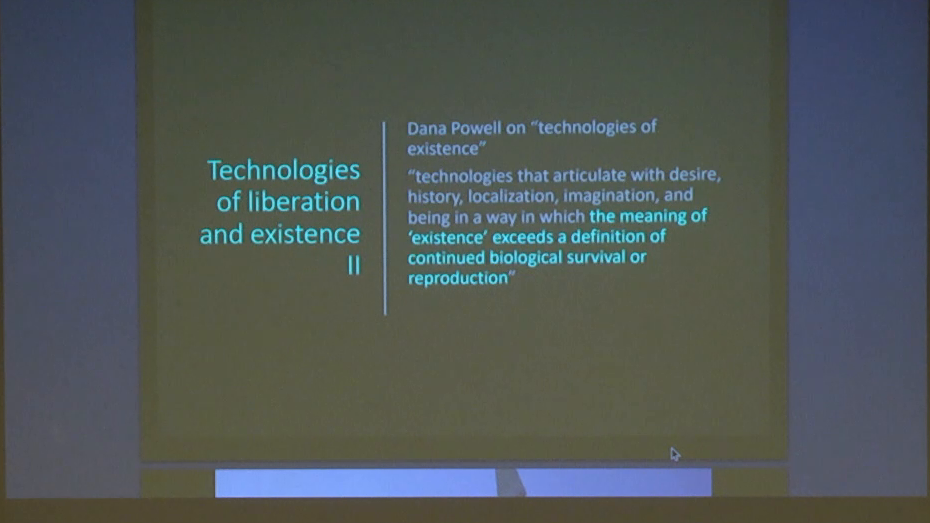

Another one that I’ve been thinking a lot about is renewable energy development on the Lakota Nation in South Dakota where I’m from. Dana Powell has called these renewable energy projects technologies of existence, where they’re not just about survival and reproduction but about liberation in some kind of way.

So let’s take a look at the KILI wind turbine, which powers the KILI radio station on the Pine Ridge res. And what’s interesting about it is it’s not the kind of like, pure white sort of uninteresting version of wind power. It’s a rehabbed, refabbed old one from the 1980s California boom. It’s painted. It powers a radio station, which also now has rehabbed solar panels.

And what’s interesting about this, then, is it’s not just the technologies themselves but actually the exercise of sovereignty over the technologies through education, training programs. These are our forms of using energy which are contributing to the ongoing existence and liberation of people from an oppressive colonial structure.

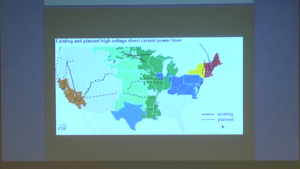

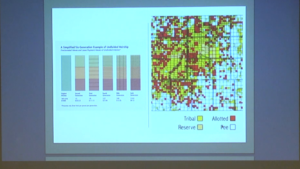

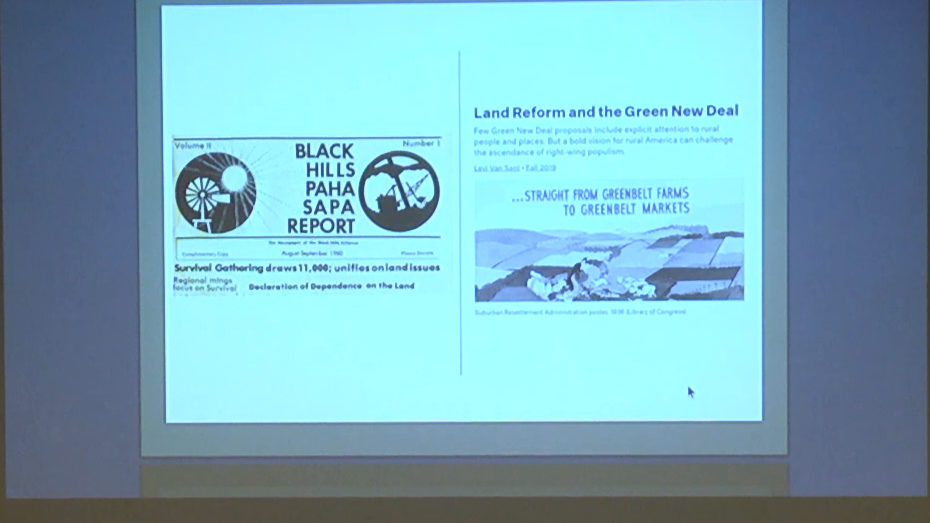

And so, of course are a lot of different ways in which we can think about the distributional or energy or environmental justice concerns of wind energy on Native nations in a settler colonial country like this one. The distributions of environmental goods and bads such as transmission lines are very important. But I also want to highlight issues of land ownership. And if we really want to think about energy democracy in some kind of way, we also have to think about fundamentally transforming the land structures of this country. It’s very very difficult to build renewable energy projects on the res because the private property structure is so fractionated. And so in this way, designing energy democracy or designing a more just future that includes renewable energy technology must actually take into account land reform.

And this is where I get really excited because some of the new conversations that’re appearing, such as from my colleague Levi Van Sant are really thinking about and connecting to long-standing movements, partnerships between Native and non-native people, which seek to decommodify land and build land reform structures that can actually then support and augment the sort of democratic decisionmaking power of multiple different communities at multiple different scales. And so obviously I think that we’ve heard in the first couple of panels many different ways in which this is not going to work if we allow renewable energy to be developed in the same sort of capitalist world system. And I think that these examples show us how alternative forms of ultramodernity or ultramodernizations actually embody then vastly different politics of technology.

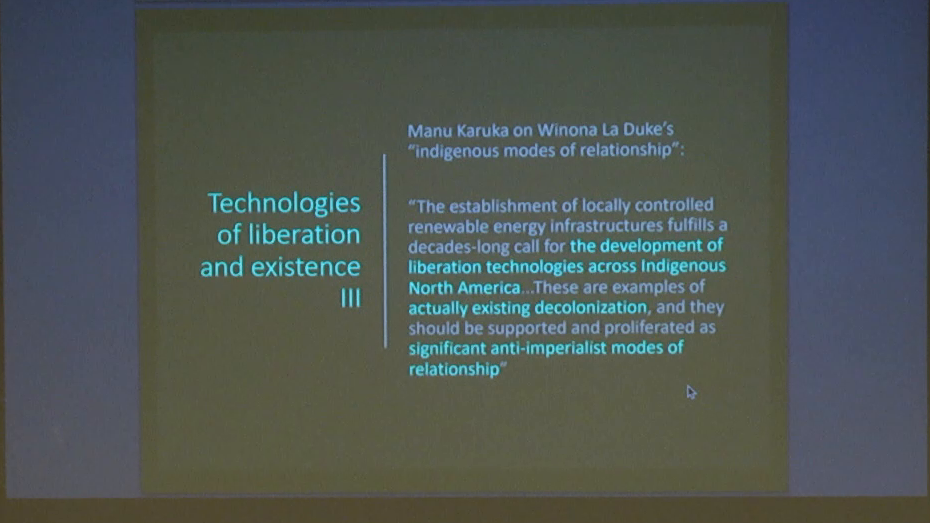

And so I’ll just end right here by thinking through, and the degree to which Manu Kuruka has called these liberation technologies. Actually existing decolonization projects, actually existing anti-imperialist projects, and not simply kind of quaint demonstration sort of things but really the real movement that abolishes the present state of things.

Okay, so I’ll just end there. Thank you all.

Further Reference

Climate Futures II event page