Anne Pasternak: Hello. Welcome, everybody. I am Anne Pasternak. I’m the new Shelby White Leon Levy Director of the Brooklyn Museum. Let’s take a poll for a second. When do I stop saying I’m the new Director? It’s been one year. Is it two years? Votes for 2 years? One year? Oh, that’s so unkind. How about five years?

Well, I’m really excited that you’re all here with us to celebrate two exceptional shows by three exceptional artists. Of course Marilyn Minter’s retrospective, and Jeremy Deller’s project, his collaboration with Iggy Pop.

So, momentarily we’re going to hear from Jeremy and Iggy. And I just wanted to share with you a little bit of background about this project. When Jeremy told me before I arrived at the museum he had a great idea, I didn’t even know the idea. I just said, “Let’s do it.” I swear to God. I’m not supposed to tell anybody that, but it is true. Other artists in the room, do not listen to that.

I had the pleasure of working with Jeremy when I was the Director of Creative Time on a project called “It Is What It Is: Conversations About Iraq”. Some of you may have known of that project. You may have seen the installation at the New Museum. But it was basically an RV that traveled around the country with a US soldier who had done three tours in Iraq, Jeremy, and an Iraqi soldier who had served in the Iraqi military. And at a time of war, talking about the people that we were at war with.

You also probably know, or many of you probably know, about Jeremy’s legendary project The Battle of Orgreave, which changed my view of what art could be and what an artist could do. And perhaps you read this summer about the beautiful, haunting performative memorial that Jeremy orchestrated to honor the lives of the British who served in World War I, as it made international headlines.

If you know Jeremy’s work, you know why I make it a point just to say yes to him, and make it a point to see him whenever I can. So that time about fourteen months ago, Jeremy shared with me a dream. He told me that Iggy Pop was a huge influence in his life. Not only because he’s an icon for punk and rock music. But he’s given us all countless moments of joy and profound inspiration, while he has also been an icon for liberating the idea of male sexuality and identity into a more fluid identity and courageous, bold, direct ways.

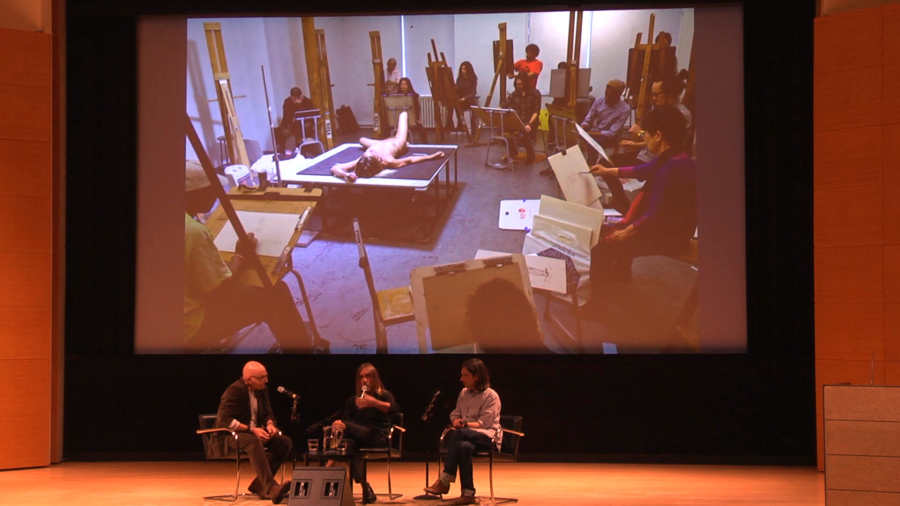

So with Jeremy’s dream in mind, last December I met with Iggy. And in March, Iggy bravely posed for twenty-two artists who gathered at the New York Academy of Art, and Iggy was the unannounced model. The artists ranged in ages from 18 to 80. And their drawings are accompanied by sculptures from the permanent collection of the Brooklyn Museum that were selected by Jeremy to take a look at cultures from around the globe over millennia and how they approach the idea of masculinity.

I want to recognize and ask the artists who are with us who participated in the life study class to please stand so we can applaud you. [applause] On behalf of the museum and Iggy and Jeremy, we’re really grateful for your participation in this project.

Now, Iggy needs no introduction. He is a singer, a songwriter, and actor who began performing in the 1960s. And in 1967 he formed the legendary band The Stooges, which was inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame just six years ago, and it significantly influenced the trajectory of music as we know it today.

Iggy’s concerts are also legendary. They are so high-energy, so intensely strenuous he defines giving it one’s all. In March, Iggy marked the release of his seventeenth album, Post Pop Depression, to critical acclaim, and he has taken a break from his world tour to be with us today.

I also want to recognize in the audience Jim Jarmusch who has just released his new documentary on Iggy. Congratulations. Sorry to call you out. Couldn’t resist.

I also want to thank a few friends for helping to make this project a reality. There was generous support for the exhibition by our friends Mike Wilkins and Sheila Duignan, the FUNd, Shane Akeroyd, Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons, Kathleen and Henry Elsesser, Cristina Enriquez-Bocobo, Gavin Brown’s Enterprise, and Charlotte Feng Ford. Thank you very much to our donors for joining us on this journey.

I hope that you all check out the book that accompanies this exhibition. It’s published by HENI Publishing. And I also want to thank our awesome stuff at the Brooklyn Museum that pulled off this project in record speed. I want to recognize Alicia Boone and my public programmings team. Alicia, where did you go? I want to thank Emily Annis in Exhibitions, and most of all the projects curator who dove in with me on this wild ride, our director of exhibitions Sharon Matt Atkins. Sharon, thank you very much.

Now I’m ready to begin, and I just want to say that this conversation tonight is going to be moderated by a dear friend, my friend Tom Healy. And if any of you have seen our new Brooklyn Talks series over recent months, then you already know Tom because he’s not only a great poet, he’s a really surprising, unexpected, brilliant moderator. And when he looks at the world, whether it’s through his writing or through these interviews, he too is seeing very deeply. So, welcome to the stage Tom Healy, Iggy Pop, and Jeremy Deller.

Iggy Pop: Hey.

Tom Healy: Welcome.

Pop: Hey.

Healy: Hey, Jeremy.

Jeremy Deller: Hello. Good evening.

Healy: Iggy, thanks for being here. So, there’s this amazing scene, a funny scene, in Cry-Baby where you’re siting in a kind of giant bucket—

Pop: Beefcake, yeah.

Healy: And you say, “Oop, you caught me my birthday suit, butt naked”

Pop: That was in a book of stills from the 50s in John Waters’ collection, a much beefier guy than me doing that.

Healy: So here you are, though. Caught—

Pop: Oh, in my birthday suit again.

Healy: In your birthday suit.

Pop: Well, I think everyone needs to feel comfortable at least once in their birthday suit before they check out. So…it’s my time.

Healy: So Jeremy, talk about this, because you asked Iggy about this easily a decade ago? And he said…

Deller: It was about ten years ago I approached him through someone. And the idea was explained. And you were intrigued, but you weren’t quite totally convinced. And I think he came round to the idea. Because I approached Iggy ten years later, and then it was like, “Yes, I’ll do it.” Very quickly he agreed.

Healy: So one of the interviews when you said you’d changed your mind, you said something really profound to me that… You used a metaphor of having weight.

Pop: No, I didn’t have the weight yet. That’s what I felt.

Healy: Could you talk about that a little?

Pop: Well… Look, I use my body, as a lot of people do that work in public, as a kind of object of commerce, frankly. When I go out and do a gig, somebody has to pay for the presence. And that’s a certain gig. When you’re still pushing a hype like that, you lack cultural weight until you get to the end of that story where everybody knows you really don’t have to anymore except for an interior reason. I wasn’t there in 2006. It was just starting to rain good things on me, but it hadn’t taken its course.

So there was that. And there was also, I was in the middle of finishing the job with my original group, The Stooges, that I had failed to complete in the 60s and 70s. And I picked that up later in life, largely through the instinct that I wasn’t going to respect myself and other people weren’t going to respect me unless I finished the first job before I went on and did what I’m now doing, which is I’m finishing the job on me.

So, that wasn’t done yet, either. In that case, it was helpful that I kept at it and kept at it. Nothing would stop me. Even when Ron passed away, I went ahead and continued the group with James, the second, Mach II guitarist. And eventually it helped us in the real world to get the support of an institution like the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. And it helped put the group in a less sordid light for the general public. [audience laughter] That’s important.

And also, every story needs an arc. If you’ve already been sordid, you don’t want to continue. “Ah, great. And more sordid from these guys…” you know. No, you need an arc. So, when you’ve been so bad, there’s only one way to go. You’ve gotta be good. And you know, the Hall of Fame is a family institution.

One of my other considerations when— [audience laughter] Hey. That’s what it is. So, hi. Welcome to the family, alright? I’m in the family now. So are The Stooges, and that’s a good thing.

When it was Gavin Brown, the gallerist, who wrote me originally about Jeremy’s idea. And he also has proposed that it would— He sort of spun it, as a gallerist will. He said, “And then we’ll give the drawings to the Smithsonian.” And I thought, “Am I George Washington quite yet?” I don’t think I qualify, you know.

But I investigated a little. He sent me a beautiful book that Jeremy collaborated on called Folk Archive. Alan Lane, was he your—

Deller: Alan Kane.

Pop: Alan Kane was his collaborator. It’s a wonderful book that treats quirky English folk people and folk customs. Things like a small village it has a monkeys’ tea party once a year. They advertise “monkeys tea party tonight!” you know. And they set out these little table for the monkeys. But they did it with the right blend of humor, casualness, and seriousness. A great book. So I liked that—

Healy: And respect.

Pop: Yeah. I liked that. But when I investigated a little farther, I realized they were going to offer the drawings also to the Smithsonian. And I thought, “Well those bastards will probably turn me down.” So another big part of it was when it came up again, I met Anne Pasternak. She reached out when she was in Miami. And this was somebody… She’s a pistol, you know.

Healy: [laughs] She is.

Pop: She had a good energy, and she was definite about what she wanted to do. And I thought, “Well, Brooklyn… Yeah, I belong in Brooklyn,” you know. I lived in Bensonhurst for a year when I was very poor. Because I couldn’t afford Manhattan anymore. And I used the B train. I lived on 86th Street near 20th Avenue in a ground-floor unheated flat. And it was a great experience. I did the album Zombie Birdhouse at that time.

The phrase the “zombie birdhouse was my way— I was a little angry— [Audience laughter; Iggy laughs.] And it was my way of describing how people live in Manhattan, basically, in these… Everybody gets a little cage in a very large stack of dwellings, and you do what you’re told like a zombie and keep going, you know.

So anyway, finally I said, “Alright. Let’s do it.” Also, you know, Jeremy keeps doing fine arts. I thought well, this is a good person to associate with.

Healy: Right.

Deller: Thank you.

Pop: Yeah.

Healy: What were you going to say, Jeremy?

Deller: Nothing, I was just saying thank you.

Healy: So, I have a hunch that I wanted try out with you that one of the things you have said about working with the artists who are here… Let’s give another round of applause to all the artists who are in the show. [audience and panelists applaud] One of the things that you say in an interview is how this is an exchange that you’re ready for, and the whole sense of posing for other artists. And what struck me is…I’m trying to think what that is. And it occurred to me that a real power of why this work is not simply that here’s the body of a celebrity. But it’s the balance between its exchange because they have this rigor and discipline and work, and you just talked about it about a job, and you have the same approach to artmaking. It’s not all about spontaneity and imagination, it’s also as a drawing class of anything teaches about art. It’s about discipline and technique and rigor, which is…your whole career shows that, too. And that kind of gets lost sometimes in a celebrity bubble. But that aspect of your personality and your career show up, I think, in this show.

Pop: I think that I can tell you, at least for me, I’ve been photographed many many many many times. And as the equipment gets more sophisticated it feels more and more like an assault. I mean somebody’s… There’s something mean about it that I don’t like. And I avoid it more and more. Some guy’s got— [makes lout mechanical sound] It’s a motor drive. He’s got this little clicker. And it’s incumbent on you to kind of stand up to that.

But in this situation, everybody was busy. They were as busy as I was. Because here’s this naked man in front of you, and if you don’t feel anything, or if you can’t draw at all, or if you don’t—okay, get down and do the work now because the dude’s gonna leave, then you have nothing. So there, they were—each one of them, you could feel was totally engaged with his or her self.

My biggest concern going in was…jeez, I… Just like you know, “I wanted to make a good first impression.” It’s a human exchange. So I was concerned with how will we meet each other before we start. Or at first I thought maybe I’m supposed to walk in, and I was like, “Okay, how’s my walkon. Do I walk in with a big cape on and then fling it off.” How do I roll this?

And then it was Jeremy who suggested, “Well why don’t we all just meet up first, clothed, in an adjacent room?” And that was wonderful. It was like a nice day in the high school I never went to. That’s what it was like. And everybody was…we had a good time for about fifteen minutes meeting each other. And then it was like, ah! And I think they felt, hopefully, like I wasn’t some kinda dick. And that’s the way I felt about them, too. Then everything could proceed, I think.

Deller: Yeah, I think it was important there was a sort of mutual respect between you and the the drawers.

Pop: Yeah.

Deller: And it just kind of broke the ice, I think. Because I think there’s probably a lot of expectation between them and you. And so it was just a relaxing thing, I thought.

Healy: Now, if I’m right, as many as like a third of the people until they were told the night before that it’s Iggy Pop, when they were told, about a third didn’t know who you were.

Pop: Well, people don’t, you know. I’m not that big a deal. [audience laughter]

Deller: Yes, but that’s interesting as well. I think it’s good that you have people who are drawing you for your body and who you are, not for any idea of you. [crosstalk] So I think that was important.

Pop: Yeah.

Healy: Right What was the biggest surprise? Because you’ve thought about this for a decade, Jeremy, and then here it is. It’s happened.

Deller: Well, the biggest surprise was that it happened. And also that once it started, the atmosphere was like being in an exam room or a library. It was very studious. Quite intense, I felt. And everyone was really working hard. It was silent, as well. There was no sound at all. It was really very intense.

Healy: For four hours.

Deller: Yeah, four hours. We had breaks, obviously. But it was just very silent, very serious. And everyone took it seriously.

Healy: And could you talk about that time? You haven’t posed for that length of time before, have you?

Pop: I’ve done…horrible photo sessions and music videos, where it goes on and on oh my God. They used to… Much longer, but not as focused or productive, frankly.

Healy: So one of things I was really fascinated by, because you’re told to hold poses for lengths of time and such. And the curator said, “Well Iggy got these because once he knew the amount of time, he had a song in his head that matched that time.” You could know alright, the pose is going to be up now.

Pop: Yeah. I was concerned… I’m not the greatest person at sitting still. And I knew I was going to have to sit still for twenty minutes, nude, seated, you know, with a bunch of people concentrating on the what I was going to be able to give them. And I didn’t want to be thinking… Have thoughts going through my mind like, “I wonder if it’s two minutes or if it’s actually seventeen minutes.” And I didn’t want to— What is the… God. There’s a great guy who does spoken word records. And he has one about time, a guy that wakes up in the middle of the night. What’s his name? He’s like, “What time is it?” I don’t know what time—”

Anyway, I didn’t want to be thinking about that. So I know, for instance, the recorded version of “I Wanna Be Your Dog” takes 3 minutes and 22 seconds or whatever. So all I had to do is I could be sitting here like this. You wouldn’t hear it. But in my head it’s like [mouths the opening notes and riff of the song]

Healy: Now I get it. Now I get it.

Pop: And you just do the whole thing. And you do the verses and the chorus. At the end I’d sing the guitar lead to myself. I know them by now, you know. And I was just sort of okay, we got a three-and-a-half-minute song, then a six-minute song… And finally at one point I said, “Is it time?” and then bong! the bell rings

Deller: Yeah, that’s true. Within a second. He got it within a second.

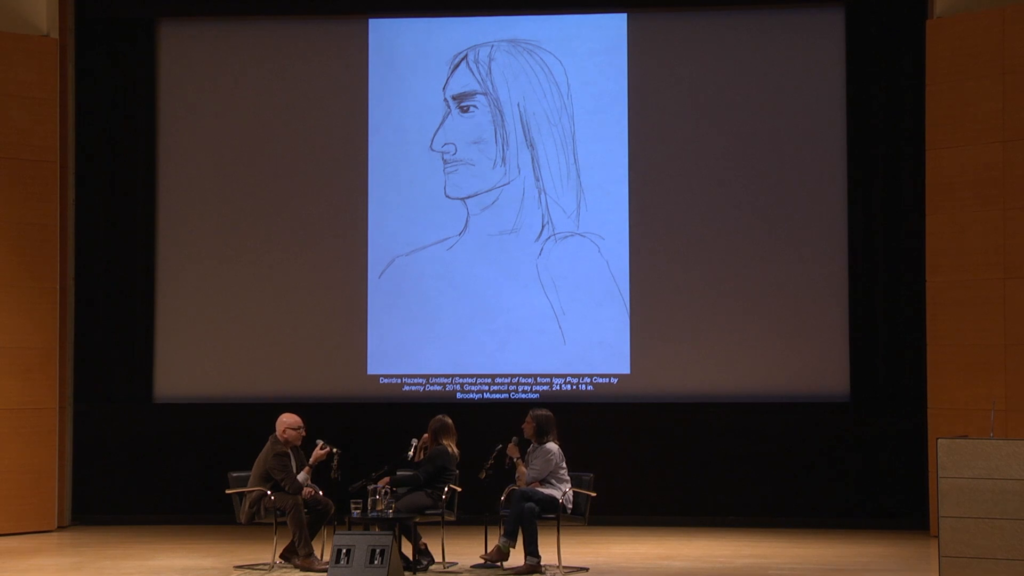

Pop: I wanted to see how close. So that was a good way, I thought, to get through it without breaking concentration because I thought I owed them concentration for some reason. I mean, one thing I noticed in the drawings, that every person… I’ve seen a lot of figure drawings before, and they tend to concentrate on the bod. But every artist gave me a face.

Healy: Yes.

Pop: They all gave me a face. Bless you for that, you know. Thank you know.

Image: Brooklyn Museum

Healy: So, we have a few images here. So this is—

Pop: That was me too damn lazy to go to my room between the takes. I said I’ll just lay down here. I’m nude now, what the hell? And he liked it, so he said, “Let’s draw that.”

Healy: So, who chooses the poses, Jeremy? How does that—

Pop: He did.

Deller: Well, Michael and I— [crosstalk]

Pop: With Mike I think, yeah.

Deller: Michael ran the class. I knew I wanted a variety. And we had to have a long pose that was seated, really. And something that looked quite heroic, I felt, holding something like a sort of a mythological figure, almost or a warrior.

Healy: Right.

Deller: But we needed a variety. I wanted to get lots of— To begin with I wanted like four quick poses so I knew I had some drawings for the show. Because [if] everything else went wrong or you wanted to leave I just thought at least we’d have something quickly. So we had a lot of drawings quickly—so we got like songs, like doing songs quickly. Almost like hit singles, almost. And then we had the long sort of concerto or sonata, whatever. We have the long piece, and that’s where all the very detailed works came from, the seated ones.

Healy: And Iggy, do you have to just let you go through all of it, or do you feel like, “No this pose is gonna suck. This is not gonna work.”

Pop: That wasn’t my place. So what I tend to before I do any—before I work with anybody, I try to think very carefully about okay, I’ll go over here but I won’t over there because that’s their turf. And also while I might be busy interfering with Jeremy, I might be blowing a responsibility of my own, I’ve learned from experience. So no, I just… You know, the seated pose. I mean, that’s tough because you know…—

Healy: Why is that?

Pop: I’m thinking, “Well. You know…here’s my penis just hanging…hanging over the side of a box, you know.” And you know, it it emphasizes your middle girth and the whole thing, and oh my god, you know. But, that’s okay. That’s okay. There’s always…

Healy: I think it’s more than okay. These drawings are beautiful and it—

Pop: Well, yeah. There’s always room for a surprise in my life. I don’t know how that works, but I just get a lot of good ideas and input from others [motions toward Jeremy] that I would not be able to get on my own steam.

Deller: Wow, thank you.

Healy: I read once where you actually said two important things you’d learned were… From Mick Jagger that it was about performance, it was work. Make a performance, you do a performance. And from Jim Morrison, you have to have surprise for there to be…

Pop: I’d say those are both true and also two different traditions. I think James Brown, Tina Turner, any good black church leader, preacher, that you see, they work it with the crowd. The more I think about the best performance I ever saw of Jim Morrison, that was a kind of comedy. There was a lot of comedy in that. And guy had a great sense of humor. He really did. And then he was able to combine that with a beautiful voice and a beautiful presence. And the band… The band was very fine, you know. He wrote well, as well. I thought he was a good writer. Some people didn’t but I think he was. Very good.

But there was comedy in the guy. You know, the first time I saw him, it was a homecoming dance, the University of Michigan, in a field house. So it was you know, the men of Michigan with their dates. And the group came out, they’d had a hit. But they hadn’t coalesced into a slick working band yet. So they play the first riff and it sounds a little weedy. And he’s supposed to come on after about eight bars. He doesn’t come on and he doesn’t come on.

And when he does—the song was “Soul Kitchen.” And when he does come on, instead of singing in his sexy baritone, he sang like this. [mimics a high-pitched voice] Made these gestures sorta like your cat when it’s rolling on its back. And he was dressed up, dressed to the nines in ruffles and leatherette. He had his hair oiled like Hedy Lamarr in Samson and Delilah. I mean, he looked wow. But he was obviously wacked, you know. He was wacked—big pupils but it was beautiful, you know. And the guys in the front got madder and madder, because they took this as a an insult because he couldn’t complete a number. So they tried another number. And another number.

And also it wasn’t at the time their sound. It was smooth on the radio, but as rock music it was revolutionary. Because most rock at the time was supposed to be more lashing and slashing and masculine. This was a not. It’s sensitive stuff. So the crowd started to approach the stage. Things were not going to be pretty and it was a short show.

And the second time I saw them—

Healy: So you were how old then?

Pop: I was…that was nineteen-six—I was 20. I had just— No, I was either—I think I was 19. I think so. And I just felt like, I was trying to get a band together and figure out how to do something creative. And after I left that show I just said if they can do that I have no more excuse. So it was like that, you know.

And the second time I saw them it was in Cobo Arena, a large arena. And they were slick and superb. And had their finger on the button. Well, you know. I remember the little folk mess better, you know. That’s normal.

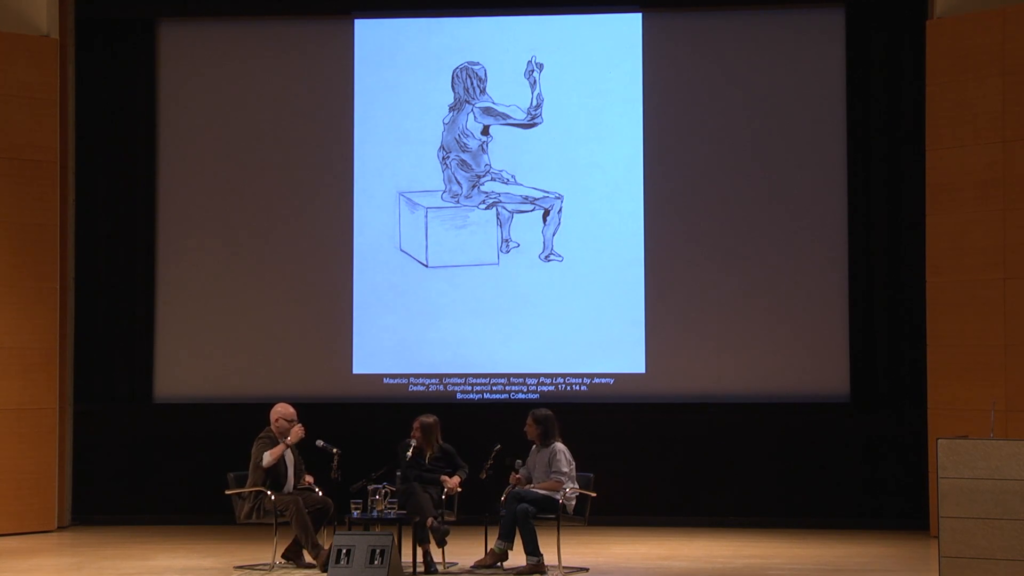

Untitled (Seated Pose) from Iggy Pop Life Class by Jeremy Deller, 2016. Jeremy Deller, Deirdra Hazeley

Healy: So you talked about the face. I love this image because it really looks hewn out of stone.

Deller: I think I said Mount Rushmore in the book.

Pop: May I see—where is Deirdra? Is she here? [waves] Right on, Deirdra.

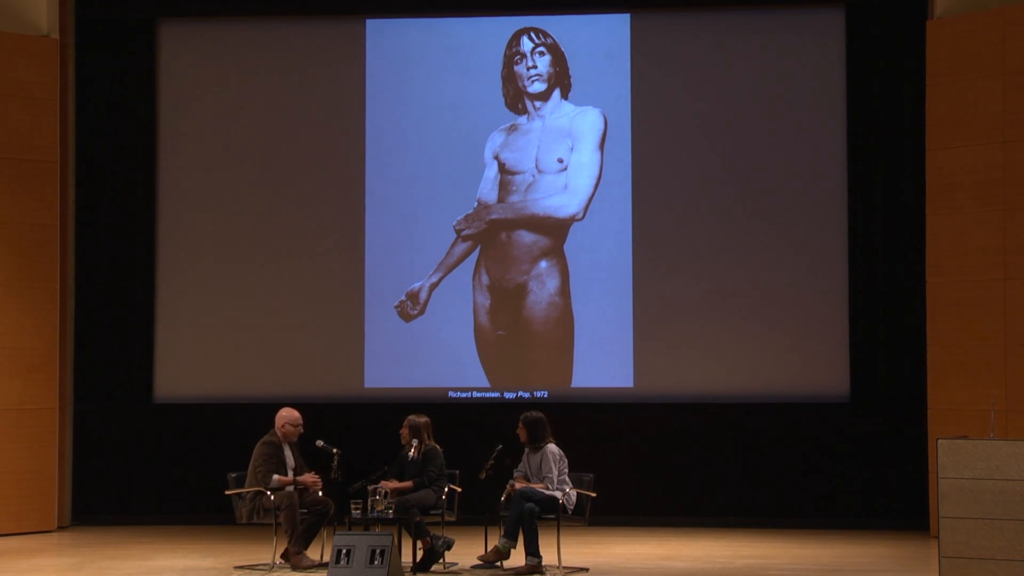

Richard Bernstein, Iggy Pop

Healy: So, you have been posing for a long time. The one image I actually wanted to have was Gerard Malanga, but we can’t use it for… But you speak about that in a really powerful way about…what is at risk in a certain way. And the coldness of that. The kind of theft of that kind of sitting. It struck me that there seem something really harsh about it that probably—

Pop: This one was tougher than the Malanga.

Healy: Okay.

Pop: Although the Gerard was mentally tough, this was tough because it was— I think It’s a Richard Bernstein piece, but I think the photo—I think this is Bill King. I think so. And I remember the shoot was like a Vogue shoot. They put you in a white room and it’s a guy whose shot hundreds of people with long necks and whatever they have. And you’re young and you’ve never been to New York City, and so you… You can see I’m kind of trying to stand up to this guy a little bit, you know. With no clothes on.

But I thought it was important somehow to me… I just thought it was important to… I knew I was going to perform for a living, for a vocation. So I thought part of the out was to document what was at the root of it. In other words no boots, no saddle. No hair gel. Whatever it is, you know. So that was why. I did it a couple of times and then left it off until this. I wanted bookends, basically.

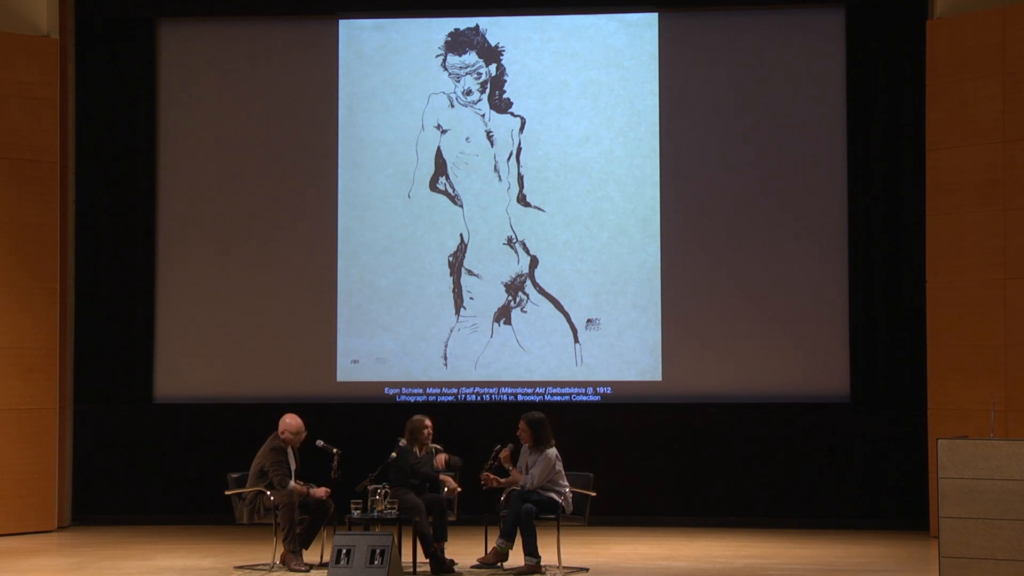

Healy: So Jeremy, talk a little bit about this for people haven’t seen the show yet. There are number of works from the Brooklyn Museum collection that are also in the show, all male nudes. And one of them is this Schiele self-portrait that to my mind looked like Iggy.

Deller: It’s amazing, isn’t it? I mean, I always wanted the exhibition to go to a museum that had an encyclopedic collection. I always wanted the work to be seen in the context of world culture, not just—

Pop: As a gift, you said to me, right?

Deller: As a gift, yeah. As a gift. And it would reside in one of those great American museums that has an encyclopedic collection. Like Philadelphia, Detroit, whatever. And the Smithsonian. But with this, I wanted to do an exhibition the male nude as well, from that collection method. And I thought it was important to show these drawings to show that they do exist in a context, and they’re part of art history. And now these drawings are part of art history as well.

And also when you consider the roots of rock and roll music, it’s not necessarily Western. It comes from other countries. And I just felt it was interesting to look up male nudes that looked at religion, that were sacred and profane at the same time. And that’s again something that was very important to the genesis of rock and roll. So I just wanted them to have a really good home in a really great museum. And had other great objects in, not just 20th century European white art, basically.

Having said, that is 20th century white art. I apologize. But there are others, as you know. But it couldn’t be in the Museum of Modern art. It had to be in somewhere that had a breadth to it. But also the kind of museum you’d go to as a child or as a young person and you’d be absolutely amazed by a Buddhist temple in one room, some Egyptian sculptures, a Renoir, or a Monet, whatever. And you’d go just time travel around the world and around time in the museum like this, like the Brooklyn Museum basically.

Healy: So Iggy, you and I were talking earlier about that. So, when you started drawing and painting yourself and you were in Berlin and you had some time, could you talk about that a little, what that…?

Pop: Yeah, I went— David Bowie took me to a wonderful little museum, it’s called the Brücke. And it was on [?], near the American sector. It was a very, very small space. Maybe the entire museum, it’s not really bigger than this full proscenium. And most of the works were not physically large works. And it was Erich Heckel and Schmidt-Rotluff and the whole German Expressionist bunch.

And I don’t know, it just… I looked at it and you know, I mean it didn’t… They didn’t try at all to be figurative. But you could just see from the color and the slash of the lines and everything, it was like yeah, this is what this feels like when I look at it. And that was wow for me, and there was something a little bit like cartoons about it. Dix is in that museum as well, who actually draws a lot like a cartoon. So it just spoke to me and I sort of paint like that, kind of. Because I can’t draw the way— I don’t have the eye that these wonderful people had. But I have feelings about the things I see or what’s going on inside, you know. So I draw that way.

Deller: We have an Erich Heckel in the exhibition as well.

Healy: Yes.

Deller: I don’t know if it’s one of the slides.

Healy: I’m not sure if it’s…

Deller: You don’t have to go…it’s fine. But I mean, I love that work as well.

[Here several slides are displayed ~35:57–36:25 while they try to find the image, which turns out not to be available]

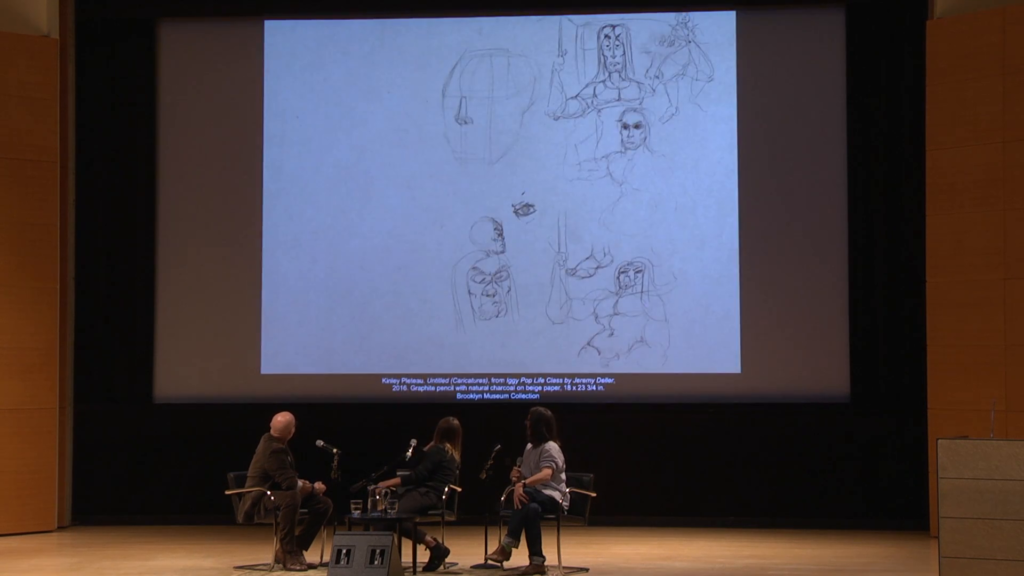

Untitled (Caricatures) from Iggy Pop Life Class by Jeremy Deller, 2016. Jeremy Deller, Kinley Pleteau

Deller: I love this one as well, actually.

Healy: Yes, talk about this, because you were talking about cartoons.

Deller: Well Kinley did some drawings, obviously. But then he was doing some little caricatures. And at the end of the class he was going to throw them in the bin. I think we’ll do something with them, and I just said, “Don’t. I want these. These are great, to have this. I love these.” They’re sort of doodles, almost. But I just thought it’s just another of looking at a face and a body, and another way of drawing. And I think he does an animation, so that’s why it has that sort of feel to it, a cartoony feel.

Healy: So when I first saw the works this week, on the wall, it was astonishing to me because they feel so three-dimensional, and they kind of move. Because there’s a beautiful book, but those reproductions are nothing like what this is.

Pop: Yeah, it’s totally different.

Healy: What is that? What happens?

Deller: I don’t know, and I think it’s very hopeful for museums because it means you always will have to go to a museum to see something. You can’t just rely on the Internet or books, even. You have to be in a room with a thing and walk around it or get close to it, and see it next to something else. Being in the presence of an artwork, there’s no replacement for that, despite how clever we are with technology.

Pop: That’s true. If you you see the Velázquez in the Prado, it’s not the same to see it in a little…it’s just not the same.

Untitled (Seated Pose) from Iggy Pop Life Class by Jeremy Deller, 2016. Jeremy Deller, Mauricio Rodriguez

Healy: This is an extraordinary…

Deller: Oh, I love this. Mauricio, yeah.

Healy: What was that like, holding…

Pop: Holding the staff?

Healy: The staff.

Pop: Oh I mean…your thumb starts to throb. There are technical aspects to holding the staff, you know. I didn’t know, I understood— I got it. I understood well, it could be a scepter, it could be a spear… I thought of it mainly as some sort of a spear. Or then I thought well, maybe it’s just a device to make visible some of the infrastructure of the bod. Because that’s what’s supposed to be behind the figures, is the musculature, the tendons and ligaments and organs. So I thought about it briefly, but mainly I did as I was asked. But when they asked me to do that particularly, I thought ohh, yi yi. And I just did it, you know, like you do.

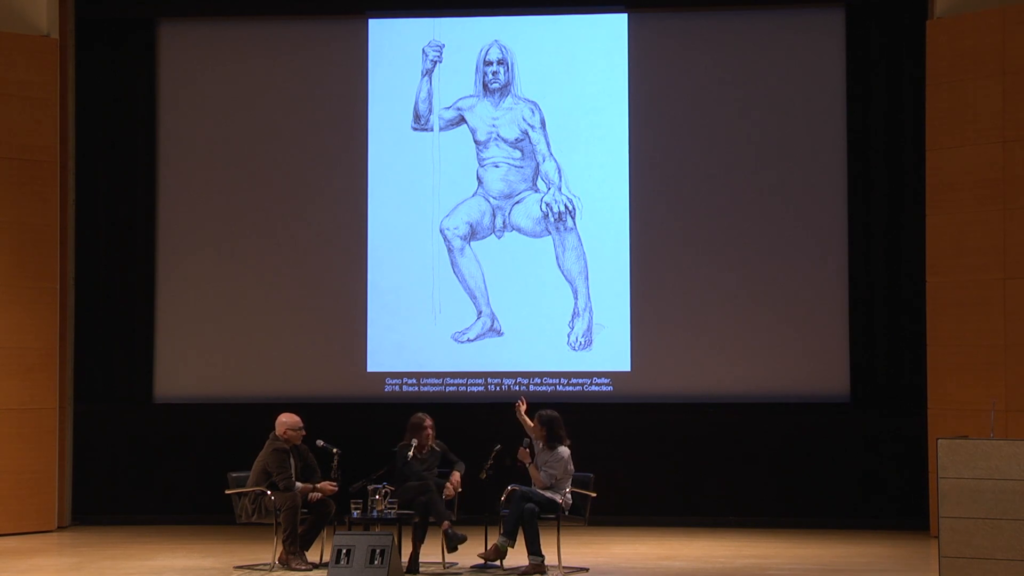

Deller: Well thank you. I did want quite an open pose, I suppose you’d call it. Because you know, it’s kind of a full-frontal pose. Guno’s drawing is somewhere. You might want to… He got kind of the best, if you go back.

Untitled (Seated Pose) from Iggy Pop Life Class by Jeremy Deller, 2016. Jeremy Deller, Guno Park

I mean, obviously that’s kind of the most open pose. And I thought that was important to have that, you know. You needed the arm out.

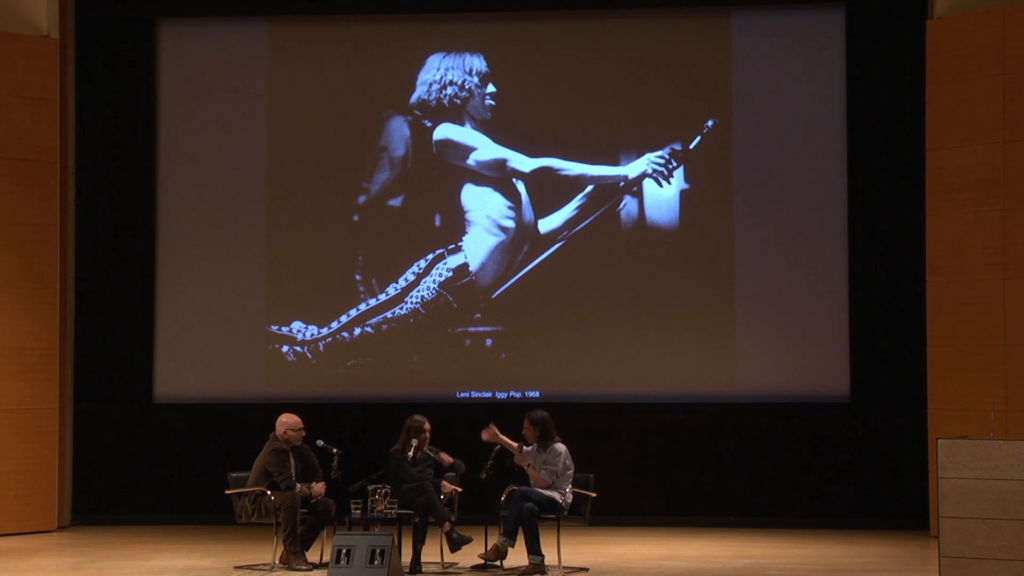

Can you go to the next picture, actually. Is it the Leni Sinclair?

I bought this photograph in a record shop in Detroit for $2.50. It was stuck on a piece of paper—it was a greetings card. And it was signed on the back “Leni Sinclair” about ten years ago.

Pop: She’s a great little artist.

Healy: Yeah. Amazing. And then see this, the tongue. And we were talking about satyrs and wood sprites and all that stuff. And I just thought this is a kind of persona, your stage persona is really in this photograph, ready-made almost.

Healy: I was thinking about this, Iggy, when you were saying every story has an art. Because there it is physically in a performance. The arc of the body, the prow of the ship. There’s surprise gonna happen in this show.

Pop: Well, I used to do that— I liked watching James Brown and also Joe Tex, who’s very unsung. But James Brown used to do this thing where he would throw the mic stand down, twirl, and when he twirled around he’d have it coming back up with a little foot movement, pop pop pop. And I thought well okay, hm. How about if I would dive head-first… I’d try to figure out what’s the length of my own body plus my arms and I’d see if I could dive and catch this mic just before I was gonna hit the deck. And that’s the moment after. Then what I would do… Then I would slither up the thing, and I thought hey…that’s a stage move, you know. Honestly, that’s I was doing.

Healy: And indeed it was.

Pop: Hey! You know.

Healy: Actually, you write and talk so beautifully about this whole range and the experimental nature of a lot of the work you did. I love when you well you know, if you take a vacuum cleaner with your thumb, it makes the sound of [crosstalk] whistling wind.

Pop: You can make make the sound of the whistling wind, yeah.

Healy: And you said well, a Waring blender with some water in it got Niagara Falls.

Pop: What surprised me, I never imagined when I used those things, I was making these sounds to enhance the very simple wah-wah guitar riffs that Ron and Scott were playing on bass and drums. Just very primal, simple [mimics a short section of music], a little funky for white fellas. But I wanted to do something besides sing in a sort of monotone manner, as I did at that time and still kinda do. So I thought well what about some beautiful sounds? And I thought that when I did these things, everyone would concentrate on the sounds, but instead they were like, “That guy’s playing a vacuum cleaner! Oh my god, this is an outrage.” They play a vacuum cleaner. But that’s not a big deal, it was a beautiful sound.

Later, I got rid of the vacuum cleaner and bought an air compressor when I got a little money. Because that was much better, you know. But that was the idea. The Waring blender was…I had failed at… Harry Partch had something called the Cloud-Chamber. And I tried to build one of those with a broomstick handle and some spring water bottles and it crashed one day.

Healy: You actually tried your own Cloud-Chamber, okay.

Pop: Yeah, and I was hitting it with little mallets and it was beautiful, but it was…not sturdy. So I thought well what about if I just buy a Waring blender—an Osterizer I think it was. So for twenty-seven bucks, put a little water in it and mic it up, it might— And it did. It sounded…it was beautiful. You know. To me.

Healy: It was to me. Jeremy, do you agree with me that this elemental thing, of that experimental kind of…the way of making a gesture in Iggy’s performative work is related—it feels like it twins with what the drawing class was? What drawing is.

Deller: Yes. It’s very basic. It’s sort of the bedrock of art history; you know, painting is drawing. Also I think his performances are very I think closely related to a lot of early performance art and body art as well, so there’s an influence there. So there’s a lot of art going on, in a sense. But definitely those performances, and of course early rock and roll as we know it, is the building blocks of everything that’s come since, anything with a guitar. And you were sort of part of that, the second wave of that in a sense. So that’s very important as well. So the elemental and the drumming—you’re right about the drumming, a very funky drumming was something that was very important. So yes, I was interested in him and that role that he’s played musically but also sort of physically.

Healy: And it was important for you with the artists who came that not only did they work with the figure but specifically that they had experience in life drawing. Tell us about that.

Deller: What, how we got the people? How we found the students, or the participants?

Healy: Or what their backgrounds were.

Deller: I wanted a real mix of people. I didn’t want to just use one class from one college. I wanted to use a group of people. Because I knew then I’d get a diverse group of people and sort of ages and backgrounds and so on. And also how long they’d been drawing for. So I wanted to have a group of people that reflected this part the world as well. So that was important. And that happened almost randomly, because we were just looking at work and then you see it when they turn up. It’s like wow, we’ve got people— We didn’t know how old these people were, a lot of them. Or where they were from, or anything.

So for me it’s very important we have a group of Americans looking at another American. And documenting a fellow American I thought was really… So in a way it’s a piece about America in the 20th and 21st century. And that sounds a very grand statement, but for me that was a very important thing, that we had a group of Americans looking at one of their fellow Americans.

Healy: And so, all of your work has really had an experience of community or family or large groups. Was there some dynamic that changed over the time? Did the artists influence one another? Did you feel something that happens…

Deller: I don’t know, you’d have to ask them that. But I think everyone’s so concentrated on their own work—that’s how it seemed. And very very…like I said, a real concentration. But I think you have a group, there must be a dynamic within the group, and that helps everyone. And I think everyone seemed to get on very well with each other, and were very supportive. So the atmosphere was a really great atmosphere. It wasn’t tense at all. Maybe a little bit before, but actually everyone was very happy to be there. And Iggy spoke to people in the breaks—

Healy: Did you peek at their drawings drawings between…

Pop: I didn’t peek, I just went over and looked at them. Yeah, sure. And kinda wanted to, I don’t know, I just wanted to meet people. So it’s just a natural thing, sorta, “Hi.” Like that, you know. I was interested. Yes, I felt really good to be there. And as the thing went on I just felt better and better. And it was like… I don’t know what the load was that I got rid of, but it took a load off my mind. Of some sort. It’s something personal, I don’t really get how that works.

Tom Healy: So we are going to open up to some questions. Here’s a question right here.

Audience 1: Hi, my question is why Iggy Pop?

Jeremy Deller: I can answer questions quite easily. Because I felt there was few bodies in America that have been so public in showing themselves to the American public. I mean, there’s obviously some people that do it for money, and in a sense they’re just… Now on Instagram and so on, just show their body off. But someone who’d used their body and was willing for their body to be seen over a period of time and to change. And also a body that really embodied—no pun intended—the culture that it came from. That really embodied rock music and was symbolic of it. So I felt it was a hugely important body in America. Probably one of the most, if not the most important body in America. And I felt it had to be drawn. And I felt that drawings could do it justice in a way that photographs can’t. And so it wasn’t like, I didn’t have a list of people to have drawn. It was just one person, basically, I wanted.

Audience 2: Thank you for coming tonight. It’s a great project. So I wanted to know if you could talk a bit about your experience posing serenely nude, as opposed to versus your performances where you’re always…you know, high-octane performances where you’re skirting with the idea of nakedness and what what it felt like for you to go from one extreme to another.

Iggy Pop: Yeah. Well, when I’m working or playing live, then I’m a sort of a technician with feeling. There are both aspects going on. And a lot goes into it. There are a lot of considerations every moment. And I’m definitely putting it out. I’m putting it out and I want it back. But I’m on. In this situation, there was none of that. I didn’t think that approach was gonna work for me. I was gonna have to try to… I was going to have to get these people to perform. It was incumbent on… I was going to have to have to try to inspire them? Or trick them? Or do whatever I could do to make them interested enough to perform. And this was something…I just kind of felt it, I didn’t think about it.

And I had to put myself in their hands. Completely. Because sure, everybody— You know, there are reasons we don’t all walk around with no clothes on all the time. And yet there are societies where people do. But not ours. And that’s something to think about right there. So I just tried to drop… I just didn’t think about myself in any way, except that I asked for a spot to look at, and then just tried to sit still. And I was trying to make sure I didn’t have a sorta… I wanted to make sure there was some energy in my mind so that there would be some in my face. And that, I used the the convention of my songs, where I’m comfortable going through my head, so there would be some expression.

So I was afraid otherwise it would be, “Uhhhhhhhhh…” Because that happens to anyone sometimes. You go slack in the wrong—if you’re in the back of a cab for two hours or whatever it is, you know. So that was it. And I felt… I don’t know, I felt cleansed of something when I left. And everybody had a big smile at the end of that session. You know, it wasn’t like “hee hee hee.” It wasn’t like that. It was just everybody…I think everybody had a good session. That’s what I thought. That’s about it. It wasn’t a gig.

Healy: So while the next person comes up with a question, I was asked a question just before we got on stage. It was essentially said this way, “You’re three white dudes on stage. And this is the Year of Yes for the museum, a celebration of the tenth anniversary of the Center for Feminist Art and a look at women in the arts. And so how does this show… How is it part of that?” Jeremy, yeah.

Deller: Oh, you want me to answer that question.

Healy: Yes, go right there.

Pop: Jeremy is the mastermind of this, I’m just the model.

Deller: For me personally, it was never intended to be that. But you know, it’s an exhibition about a body. It’s about a body that sort of in some ways has been under the amount of intense scrutiny that only usually women’s bodies are. And it was quite interesting when we had some comments on social media when we did this, when we released some photographs. And some people were saying, “That’s great,” and some people were saying, “Oh my God. What’s going on? This body…this guy, why are you drawing him?” And in a way you sort of got an idea of what it is for a woman to be examined and sort of be judged on a body of a certain age and a certain way. But I would say really it’s more…it’s a show about a body, and and about the sexuality of that body as well. How it’s been viewed through time. So I can’t exactly answer your question, but I always saw it I suppose as a sort of…there’s another element of kind of an asexual element about it as well, about the body, about the way it’s used.

Pop: I partly had an answer which I think is question more than answer as well. But I think there’s a really brilliant pairing of this show with Marilyn Minter’s terrific exhibition that’s opened down the hall from this. And there will be a number programs with her. She’s an extraordinary artist. I hope she’s here. But part of what seems to happen is that there is a conversation of, what Marilyn does so brilliantly is take control of a number of the tropes and abuses and controls that the male gaze, or even the commercialization of the women’s body from the male gaze, has done to it and made extraordinary art from it. And the art made from you is actually this vulnerability about that male control and turning it over.

Pop: That was the word I would’ve used. I think…someone named Francis, what’s her last name, that wrote the wonderful—

Deller: She’s probably here, and I can’t, it’s Bowles…? There she is.

Pop: Is that you? Hey. She wrote a very perceptive and interesting history of life drawing in the middle of the of the booklet for this thing.

Healy: It’s terrific.

Pop: And I learned that this started out in the Renaissance as a kind of a— Your task was to illustrate beautifully what they thought was the important history of mankind, which was always the religion and the great heroes and blah blah blah. It had to be beautiful, it had to be technically superb. And this, it was always men that were the objects. You could not do it, never never a woman, for a whole lot of reasons. First because women were considered inferior specimens. Because they were fleshy and whatever.

And then that somehow things switched. Much later things switched over, and the idea in France of the boheme and you know, she’s my model but also my lover. And then the male gaze of course and the whole fashion industry of today comes from that. And then she sort of put, “and with this exhibition, in steps Iggy Pop.” So where does that come in?

And I knew that at sixty-nine years old, I was not going to be… This was not going to work if I tried to make myself the object of the male gaze. I did that pretty well when I was twenty-nine years old. This is different, you know.

Healy: I don’t know, I think you’re pretty hot, Iggy.

Pop: Well thank you. So yeah, I think the chick has always been in the vulnerable position. But you know, it’s kind of fun, guys. You should try it.

Audience 3: Hi, Iggy.

Pop: Hi!

Audience 3: Hi. So it’s not really a question, but I’m here representing a Japanese [?] to ask you to come to Japan to have a show as a part of Post Pop Depression. So I collected a thousand petition from Japanese fans. So may I pass here?

Pop: She has a bunch of signatures on a petition?

Healy: Yeah, I guess so.

Pop: Bless you. Thank you.

Audience 3: Please come to Japan.

Pop: Alright. Thank you. Bless you.

Audience 4: Hey, Iggy.

Pop: Hey, man.

Audience 4: Personally I just want to say thanks for all the music because man you made my life so much better.

Pop: Hey, alright.

Audience 4:And I really can never thank you enough for it. I’ve done the live model thing before. Were you cold?

Pop: You do what, you do model things?

Audience 4: I did it twenty years ago.

Pop: You used to be a model.

Audience 4: I did it like twice. And I was really cold. That’s what I remember. So I was just asking, were you cold during your…

Pop: Oh, cold. It was a little cold in there, yeah. They did try to give me a break, I remember. They talked about that due to my you know, well. They give me a break. It wasn’t that bad. Wasn’t that bad. You got the short end of the stick, eh?

Healy: Well we got the long end of the stick. So thank you Iggy, thank you Jeremy.

Anne Pasternak: It was really really cold in them there, so it gives you a sense of how impressive Iggy is.

So I wanted to answer Tom’s question for a second, because all of their answers were great, about how this fits into a year of feminism. As you know at the Brooklyn Museum we’re celebrating the tenth anniversary of the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art. For an entire year we’re devoting the museum to the lens of feminism. But it’s not a feminism of of my generation or my mother’s generation or my grandmother’s generation. It’s a feminism for the future, that takes a look at gender equity, inclusion, and equity at large. It’s a civil rights movement and so everybody fits into this movement. Everybody fits into feminism.

So I want you to know that Marilyn Minter is doing a marathon of interviews here next week. We hope to see you back again. If you haven’t seen the Jeremy Deller/Iggy Pop Life Class exhibition, it’s up on the fifth floor. I urge you to see it. It’s fantastic. And also Marilyn Minter’s show. And I thank you all for joining us tonight, and thank you Jeremy for your brilliant vision, thank you Iggy for all the inspiration, and Tom.

Further Reference

Event and exhibition listings, at the Brooklyn Museum site