Golan Levin: And we’re back. Welcome back, everyone. It’s Friday night of Art && Code and we’re having our final presentation. We will be hearing a presentation by Virginia San Fratello, who works collaboratively with Ronald Rael. The two of them create artifacts that are deeply influenced by craft traditions and contemporary technologies. Wired magazine has written of their innovations “while others busy themselves trying to prove that it’s possible to 3D print a house, Rael and San Fratello are occupied with trying to design one that people would actually want to live in.” They are founding partners of the Oakland-based make-tank Emerging Objects, and they speculate about the social agency of architecture in their studio Rael San Fratello. Please, this is Virginia San Fratello. Thank you so much.

Virginia San Fratello: Thank you Golan for that introduction. I’m super excited to be here tonight to have the opportunity to share a project that Ronald and I have been working on for the last two years. It’s called Mud Frontiers.

And it’s called Mud Frontiers for two reasons. One, because we are quite literally building with mud. And two because we’re working at the frontier of technology, using robotics and 3D printing. But also because we’re working at the historical frontier between the United States and Mexico. So we’re here in this photograph, and here in my studio now, at this frontier in the San Luis Valley which spans central/southern Colorado and northern New Mexico. So this is I think the highest alpine desert in North America. So it’s a very extreme and very beautiful landscape.

It’s also a region where locals have been building with mud for thousands of years. So about forty miles to the south of us is the Taos pueblo, which you can see here in this photograph. This is a building that has been made of mud, adobe bricks, and mud-plaster. It’s the oldest continuously-occupied building in the United States. And until recently, maybe about a hundred years ago I would say, mud was the most prevalent building material on the planet. And it has more recently been replaced by cement.

So, we’re looking at mud frontiers and thinking about Mobility, Ubiquity, and Democracy.

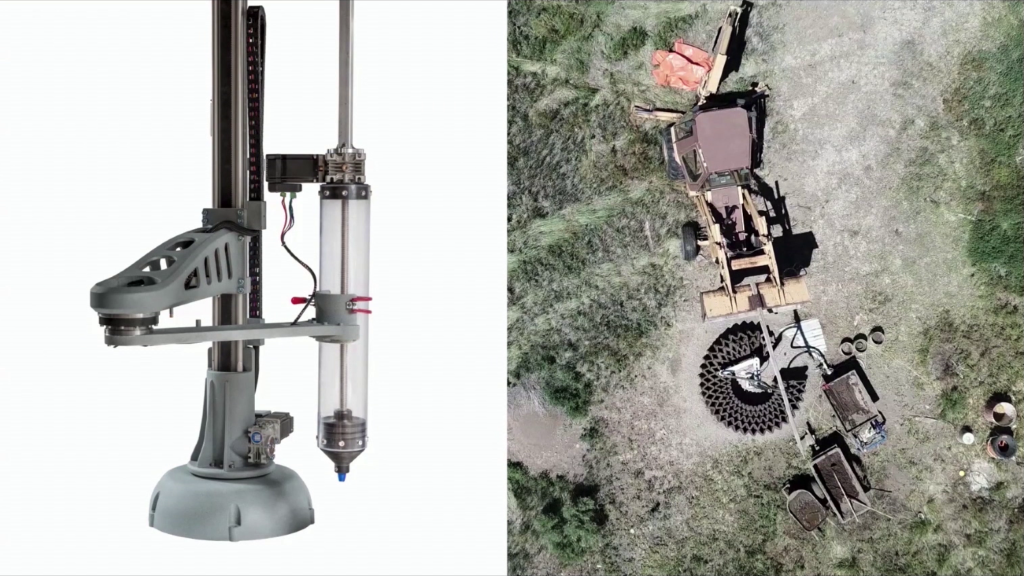

So, mobility. We have developed a mobile robotic setup. So on the left here you can see the robot arm that we use. It’s very small. One person can carry it. It’s very lightweight. In this case you see we have a tube attached as the end effector and we can use this to extrude materials like mud or clay, or…really any kind of paste can be pushed through this.

In the right photograph you see our fabrication setup here on our ranch in the San Luis Valley. And we’ve taken that tube off and we’ve connected the robot to a continuous flow hopper. So we can continuously push mud through the nozzle, and the robot will move around and print the pattern that we have designed in the computer.

Ubiquity. Of course soil, mud, dirt can be found everywhere. We’re literally using the ground beneath our feet; the mud and the soil from the site where we’re building at our home here. You can see in this photograph we’re mixing the mud with water so that it’s more fluid and goes through the pump more readily. And chopped straw. And that chopped straw gives our structures increased tensile strength, and it also helps wick out the water so the mud will dry a little bit faster after the print.

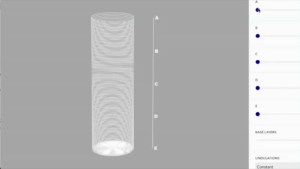

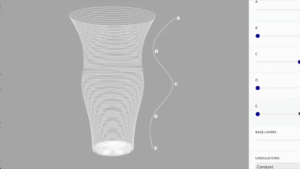

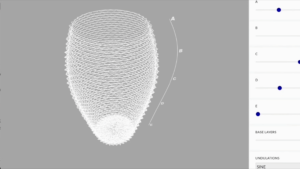

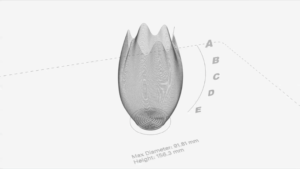

Democracy. We’ve developed an easy-to-use software called Potterware that runs in the cloud. You can see here in this animation it uses sliders, so you don’t have to know how to 3D model anything. You don’t have to know how to slice the G‑code. It’s really intended to be for novice users who need to design things very quickly and very easily. So you can make a form, you can design a texture to go on that form, and the software will automatically slice it for you. And it’s ready to print within minutes.

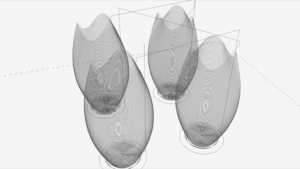

We’re also experimenting with non-planar surfaces and giving users the ability to make multiple prints. And in a more recent iteration which we just released this week—if you go to potterware.com you can play around with the tools and see the newest version—we also allow users to upload a black-and-white image so they can embed that image onto the surface of their 3D print.

So we’re using a slightly more robust version of this for the larger structures, but for now this is available to anyone—to students, to educators, to professionals—if they want to experiment with the software and use it to make their own custom 3D prints.

So over the last two summers we’ve been developing this Mud Frontier project in the San Luis Valley. And we’ve created I think about five different structures. So we have a little village going here which you can see in this photograph.

And we’ve conceived of each structure in a different way, as a way of kind of testing different ideas that we have about how to use this technology with this material. This particular structure is called the Beacon, and it is an exploration in light. We printed one single line here, so the structure is very lightweight. And the crenellation in the wall actually is what gives it the strength. And we’ve used lights to light up the concave and the convex surfaces to highlight the lightness of the structure and the thin surface.

This structure is called the Lookout, and here we were exploring structure actually to see if we could 3D print something out of mud that would be strong enough to support the weight of a body. So we created this staircase, and you can walk up the side of this and stand on top of it.

And in this photograph you can see the robot arm printing this pizzelle-like structure. So it’s a continuous wave that is underneath the stair and the platform. So this is what the interior of that structure looks like. And it’s quite strong.

This is the Kiln. This might be the world’s first 3D-printed kiln. So, this structure actually has an inner and an outer layer. And we dug a pit in the center of it, and we use it to pit-fire the smaller 3D-printed clay pieces that we make. And we use local juniper, which you can see here and the doorway. And this opening faces south so the wind comes in and it creates kind of a vortex in the interior of the kiln. And it gets really hot in there so we’re able to fire our pieces to a pretty high temperature.

And this one we call the Hearth. So this was another study in structure, but in a different way than the Lookout. So in this example, this particular form has an inner and an outer layer, so an inner coil of mud and an outer coil of mud, and those two layers are tied together by these thin pieces of juniper. So as we print, as the robot prints, then we come behind the robot by hand and lay down those juniper sticks. And those juniper sticks tie the inner and the outer layer together to make it stronger. It also creates this beautiful kind of furry aesthetic which I really like about it.

And then on the interior we have a hearth, which is also printed out of the mud, and a bench where people can sit around the fire and gather in this protected interior space.

And more recently we’ve worked on a project that we call the Casa Covida, which is a house for cohabitation in the time of COVID. And in this project we’ve extended the logic. So instead of just printing one form at a time, we’re now able to print multiple consecutive forms through the creation of this fourth rail which is this wooden element you see, which allows us to move the robot on the horizontal axis.

So instead of printing… I think we can print about sixteen to eighteen inches high at a time, and then we have to stop and let it dry. So instead of waiting for four or five hours for that to dry, we can just move the robot and start printing again, print another eighteen inches, move the robot horizontally again, print another eighteen inches, let it dry.

And our fabrication setup is really dependent on climate and weather. We can print sixteen or eighteen inches and if it’s a sunny, windy day like you see in this photograph here, we can wait two or three hours for the mud to dry, and then we can start printing on top of it. But if it’s a cloudy day, maybe just a little bit rainy, we might have to wait twelve or eighteen hours before we can print again. So we’re really dependent on the climate, and we have to work very closely and tangentially with the weather.

So we’ve created these three rooms that are adjacent to each other in the Casa Covida.

And the room you see here is the entrance. It has a hearth and seating.

This room we’re in now will be a room for bathing. And the room we started in, where the camera was, will be a room for sleeping.

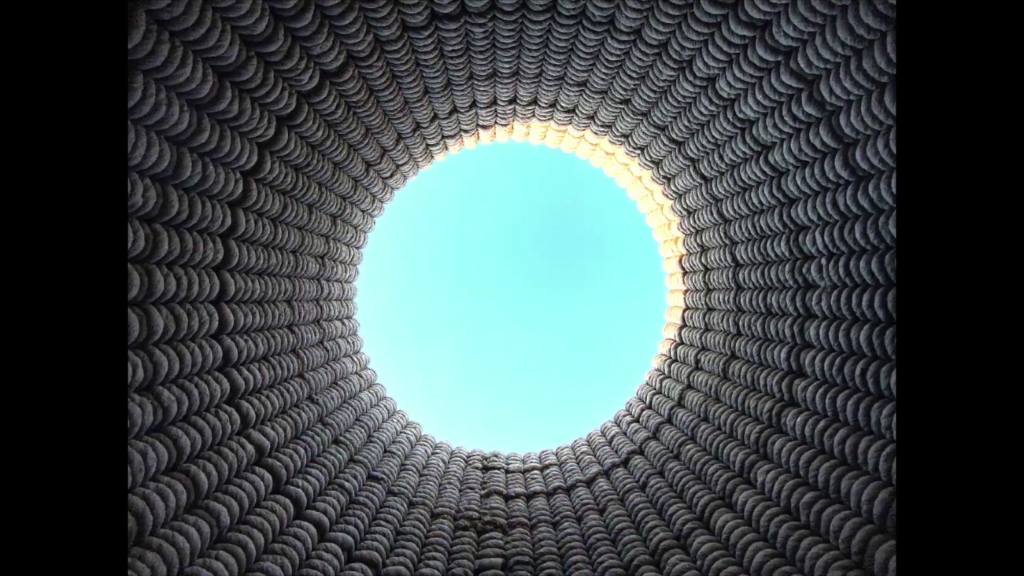

And in this video you can see how we are using the robot to create two layers. And this is because as the walls come up they create a frustrum, or a truncated dome-type shape with an oculus at the top. And as that outer wall leans in, it’s supported by the inner wall. And the frequency of that inner wall is twice what the outer wall is, so that those waves will touch and support each other as they continue up.

In addition to extending the…I guess the reach of the robot horizontally, we’ve done it vertically as well. So the robot arm itself is only about six feet tall. So we built this plywood box so we could lift the robot up and print to heights for example twelve feet tall, which is what this particular structure is. And the robot has wifi. So you can see my partner Ronald there using his smartphone to drive the robot. So it’s very very mobile and easy to use.

Another innovation in the Casa Covida is the use of lintels. So if you look closely in the photograph you can see a black piece of wood. It’s a piece of beetle kill pine from the beetle kill-infested woods here surrounding us in the San Juan Mountains that we’ve charred black and then we’ve printed on top of it. So this allows us to create openings in the walls.

And here, the very last layer. Each dome has an oculus on top, which allows for beautiful framed views of the sky.

And this is the current state of the Casa Covida. This is the entry where we have the hearth, with a fire in it. And we’ve developed custom textiles for the benches. You can see the door to the exterior.

And the kind of beautiful, textured services that’re created by these sine waves on the interior wall. This is the room for bathing. The bathtub is made out of a water tank that the ranchers used to water their cattle with here in the valley. And it’s surrounded by polished river rocks.

And of course this beautiful view to the sky through the oculus.

And then the room for sleeping is clad with these local sheepskin pelts and custom textiles.

On the eve of Smithsonian Magazine’s fortieth anniversary, they made forty predictions for the future. And number one on that list was that sophisticated buildings of the future would be made out of mud. And it’s our aim through this research to make that prediction come true.

So, in addition to the work that we’re doing out in the field, we’re also developing smaller objects for the interior of the Casa Covida. So using the 3D printer which you can see here behind me, we’re also printing objects that we can cook with.

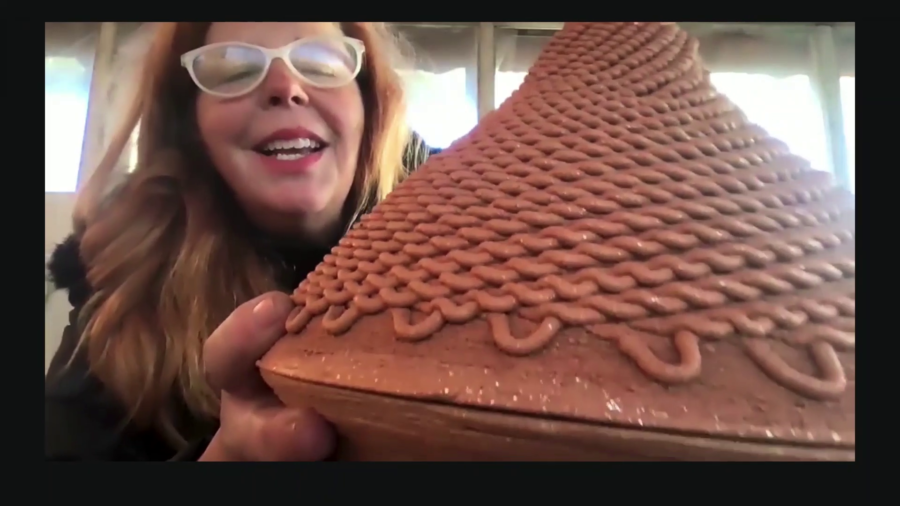

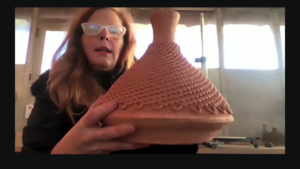

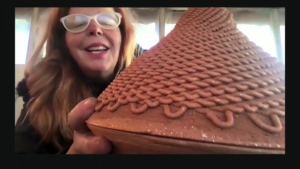

So we have here a tagine. This. So this tagine is printed out of micaceous clay from New Mexico. And the clay is incredibly beautiful when it’s fired in a kiln. It turns this orange color and it has these little flecks of mica in it—I don’t know if you can see it on the screen or not. The mica of course makes it a beautiful, sparkly object. But they also do something else. They absorb the thermal shock that the pot receives when you put it on a fire or on a stove. So we’ve been making these and actually cooking in them. A friend of ours is a local rancher and we buy a sheep from him every year so we’ve been making lamb stew in the tagine.

Let me show you another one. This is a bread loaf pan. So this is also 3D printed using the robot. It’s also made out of the local micaceous clay from northern New Mexico. But this one is black because it was pit-fired in the 3D-printed kiln. When we put it in the ground, we smother it with the juniper and with grasses and remove the oxygen from the place where the piece is being fired. And that causes it to turn black.

We’re also printing with another clay which is from New Zealand but it has a history here in this region. There used to be a factory in Pecos, New Mexico where they made dolls and buttons. And this porcelain is called Pecos Porcelain. And the formula was developed here in New Mexico for that particular application. So we’ve been using the Pecos Porcelain to make candlesticks, and this is a soap pail for example, which will go in the Casa Covida by the room for bathing.

And I want to show you just a few more things that we’ve been making to go in the interior to kind of soften it and to make it functional and useful.

So we’re working with a local weaver here. His name is Josh Tafoya. Josh has an interesting story. He was a fashion design student in New York and graduated this past May during the shelter in place. And he had to leave school and come back to New Mexico. And he was sharing with us that he came home and he wasn’t quite sure what he was going to do because he thought he was going to work for a fashion designer in New York. But he discovered in his return home that he came from a family of weavers. And so his aunt gave him her loom and he’s been using the wool from the local churro sheep to weave clothes and textiles. And so we asked him to weave some pillows and blankets for us that take on these graphic motifs inspired in this case by the floor plan of the bathing area within the Casa Covida.

And here in this pillow you can see the floor plan of the entire Casa. So here’s the door, here’s the hearth. This is the room for bathing. And then this is the room for sleeping. So it’s been really lovely and wonderful I think to discover local craftspersons, and for us to also realize there’s this kind of amazing diversity of material with which we can work.

I think the last thing we have to do for the Casa Covida is to make a door. And one of our ideas is to make it out of wood. To use the local beetle-kill pine and to char it black. And we also want to make a cast aluminum handle for it.

So, during this time we got a pet, a cat. And we realized that of course the cat eats a lot. But these cat food cans, these Frisky cans it turns out are 100% aluminum. So we bought a crucible and 3D printed a master, and used those cat food cans to melt them down to make these beautiful aluminum objects from our 3D prints. So the next step in the Casa Covida is to make this hardware, again using a kind of local material. And that’s what’s happening now. That’s where we are. Thank you.

Golan Levin: Thank you Virginia. That was amazing, and such a lovely opportunity to see both the objects you’re working on small and large. So the Discord chat here’s hopping with questions. Everyone’s like “how this,” you know. So if you don’t mind I’ll just dive in with a few questions here.

So I’ll speak as someone who—you know, I’ve worked with 3D printers for a while now. And you just bump them and you know, they get misregistered and they’re pretty finicky, crappy things often. What failures/mishaps have happened working at this large scale, perhaps when nature hasn’t cooperated? And a related question to that is sort of how do you ensure the kind of registration that’s needed from level to level when you’re printing these kinds of things?

Virginia San Fratello: Failure… [laughs]

Levin: Tell us about the failures. Because these things look extraordinary, right.

San Fratello: Yeah I mean. There’s not that much failure, you know. Sometimes the mud is too dry, right. And then it won’t get pumped through the hose, right, it gets stuck. And then we have to clean all the mud out, and we have to clean the auger out. Yeah. And that’s a problem. It takes a lotta time. Suddenly you lose four or five hours because you have to clean everything out, you have to mix the mud, you have to make it more wet. We put dish soap in it, and that helps keep it moving. So that’s kind of a solution to that problem. Yeah. I would say that’s maybe the biggest problem.

Levin: One person writes, “Such beautiful structures, but your mention of the future of mud construction reminded me of a devastating earthquake in Iran in 2003 that was particularly deadly because the buildings were made of mud,” and I think probably unreinforced or something. “Can you expect to how seismically sound these mud structures are?”

San Fratello: Well we’re not in a seismic zone here. So we’re not having to deal with that issue here, right. But you can have reinforced mud bricks. I think they do have a little bit of cement in them. I think you could— I am not an expert on that so I’m probably not the best person to answer how to make the adobe structures or mud buildings kind of seismically resistant. That is a reason why they’re not built in California anymore, for example.

Levin: Sure. There are more question about like how did you perfect the mud/straw/water mix? Was there a traditional craft recipe, or did you just sort of tinker with it and experiment with it? How much did you have to adapt for extrusion through a…you know, robot.

San Fratello: No, that’s a really good question. And because this is a region where people have been building with mud for so many years, there is a tacit knowledge that has been passed down from generation to generation like where to go to get the best mud, where to go to get the pink mud, right, where to get the brown mud, the red mud. And this is about the right mix, and you can stick you hand in it and feel it. So yeah, it’s like baking a little bit, you know. You work by tasting it, right. Oh, it has the right amount of sugar in it or, oh it has the right amount of straw in it.

So we don’t have an exact formula, again because some days the water evaporates faster than others, so we kinda go by that tacit knowledge and feel.

Levin: The pockets in the walls between the layers look like they would allow for insulation. Have you considered that, and also how a roof might be designed to allow for a comfortable structure in a cooler climate? Which you’re in right now, you’re in a cooler climate.

San Fratello: We’re in a very cold climate right now. It’s exactly freezing right now. As soon as the sun drops it’s gonna go down to about ‑10 tonight.

But yeah, the spaces in between the waves are air pockets, and we have considered that those would provide excellent insulation, especially…you know I showed you that pizzelle structure underneath the stair. Which is probably about two feet wide, and a typical adobe wall might be two brick wide. So pretty close to that. And we would get really good insulation in a place like this, not only because you have the insulative quality of the air but you have the flywheel effect and the thermal mass of the mud.

Levin: There’s many many technical questions. How did you arrive at the wave pattern? But I think you sort of answered that in your talk, where you’re sort of saying the wavy structure gives it a certain strength.

San Fratello: Yeah. The wavy structure is stronger than a straight line, for sure.

Levin: Is there some kind of Holy Grail or really ambitious thing that you’re like, “Shit, I wish we could do that?” Or is the Casa Covida kind of the project which is the current Holy Grail?

San Fratello: No, no. There’s always more. We would really really like to build a bigger robot so we can make bigger rooms. And we would really like to make a functioning house and you know, button it up with a door that closes, and a roof, and have plumbing and electrical in it. And show that this is really a viable way of building for the future.

Levin: So you have this ranch or property. I guess it’s probably littered with buildings. And Madeline asks, “Is there a 3D-printed graveyard of 3D-printed stuff on your ranch?” Are there all these kinda like shanty shack 3D-printed blobs that didn’t work out?

San Fratello: You know, no. Because when they collapse…going back to the failures…sometimes things collapse, right. We recycle it. So we scoop it back up and put it back in the printer. Because it’s hard work, digging and mixing that mud! [laughs]

Levin: You can recycle the mud.

San Fratello: Yeah!

Levin: So you just chop it up and add water.

San Fratello: Yes.

Levin: Whoa…

San Fratello: You know, these structures, they will just melt into the ground. They’ll disappear one day.

Levin: This gives us a lot to think about.

Virginia San Fratello, thank you so much for sharing your work with Ronald Rael. It’s really lovely to see this work, and I hope you get to enjoy the rest of our festival. We’ve got great presentations tomorrow. Thank you so much for sharing this work. It’s really gorgeous and it’s very stimulating. I with you the best of luck in realizing a future full of mud houses.

San Fratello: Thank you so much, Golan.