Golan Levin: Good morning, everyone. It is Friday of Art && Code: Homemade. My name is Golan Levin, professor of art at Carnegie Mellon University and director of the Art && Code festival, and it’s my pleasure to welcome you this morning to the Friday morning session of Art && Code. We’re going to have three presenters this morning at 10:00 AM, 10:30, and 11:00 AM. They are Max Bittker, LaJuné McMillian, and hannah perner-wilson.

First up is Max Bittker, who is a teacher, artist, and software developer interested in tool-sharing as a creative practice. His practice combines an appreciation for the limitations of digital materials with patience and care for human needs. Max Bittker.

Max Bittker: Hey. Good morning. Thanks for having me. I’m really excited to be…I guess at the Art && Code festival. My name’s Max. Thank you for the introduction.

I guess that I wanted to preface my talk a little bit with the place that I’m coming from, which is I think that I’m somebody who has been making making simulations and games for a long time, and that’s been a way that I’ve tried to understand the world. And it’s been something that I’ve gotten a lot of joy from? But I’ve always had a little bit of like, a monkey’s paw thing happen when it’s hard for me to share that joy with other people because on one hand computers in the first place just are so frustrating. Trying to create art with them and express yourself, you all can imagine the things that go wrong. But also I think that naturally when you try to express an idea with a computer it comes across as maybe opaque or doesn’t necessarily invite someone inside.

And so, the ways that in my practice I’ve tried to deal with that have been to I guess like, make not just simulations or games but also to make tools that really put the creative power and the expressive power in the hand of the person who’s playing with them? And additionally I think that I’ve tried to make things that expose the internals of the way that they work. And so computers are by default kind of opaque, and I think that any time a system can put a glass lid on what’s happening inside, or make it audible in some way, is one step that you can take to share and make that less of a single-person experience.

So, I was teaching this fall to a class about designing tools. And I think that my favorite resource that I’ve drawn from and drawn from in my own practice is that there’s this zine by Kate Compton called Casual Creators: Designing Tools for Casual Creativity. And this is a very wonderful and short PDF you should totally download and read. But the premise is kind of that humans do so much creativity for the sake of its own joy and for the sake of communication that can be so fun effortless. But oftentimes creation processes on computers don’t capture that same thing—even if they’re still very powerful and expressive. And so, the zine itself kind of draws some connections between what it thinks that oftentimes things like crafting supplies provide to somebody that Photoshop does not.

And I guess that when I was thinking about this festival and about the concept of craft and being homemade, I was thinking about this zine, and I was thinking about I guess designing creative environments or creative materials and tools for people, and reflecting on what craft is to me. And I think that I see craft as…one thing that I love about it is how closely it is connected to its materials. And so when I think about a crafted object, oftentimes that’s something where the materials that went into it are very exposed and visible, proudly. And because you can see the grain of the wood, or the stitches in the material, it’s also visible to you like the act of—like the process of the creation is very visible in the final result. And not only does that connect you to the process of creation but it also connects you to the person who created it. Because their fingerprints are kind of left exposed. And so to me, that’s one thing about crafted objects that draws my attention to their relationship with materials.

And I guess that when I say material, just for like a syntax disclaimer for the rest of this talk, I’m talking about matter from which…or a thing that another thing is or can be made. This is a house made of wood. And a thing about materials is that they in themselves are oftentimes made of other materials. So it gets a little bit confusing.

And when I say materiality, I guess that I mean the influence on a thing of the materials that compose it. And so this is a skeleton that is composed of pasta and glue. And it’s not just a coincidence. Like, it matters that it’s made pasta and it affected the experience of the person who made it, it affected the shape and the way that it looks, and the way it fits together, and the decisions they made. And it also affects our experience perceiving the pasta skeleton and what we think about it. And so that’s its materiality to me.

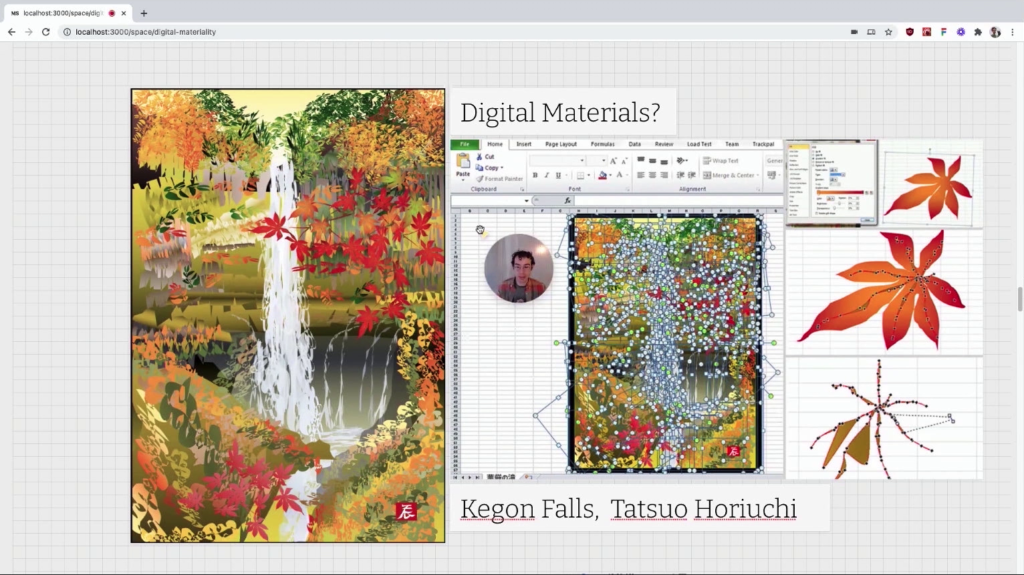

And similarly, I think that in the world of digital art, digital things are made of digital materials, and they have a digital materiality. And so this is a painting that is made inside of Microsoft Excel, actually, using the line tools. And it has properties that are connected to the fact that it’s in Microsoft Excel. It’s not just an implementation detail.

So, quickly I wanted to go through like five ways—and this was just my attempt to maybe list out different ways that a material supports a creative process. And so, starting off with maybe obvious is that a material gives you your properties that you exist in the world with. And so, if you want to make something that has mass or volume or tensile strength, or a color, there’s no way to do that besides through adopting those properties from a material and then combining them in a different way. And so I guess that I didn’t want to leave this one out, because it’s basically like, materials let you make anything at all but I also don’t exactly know what to say about it?

And I guess to move on to this one which is maybe the corollary, is that not only do they provide physical properties, but materials also impose their own limits and constraints. And so, this can be a frustrating thing, obviously. But it also I guess is part of the process of mastering a material, or learning to work with it is learning to appreciate its constraints and its limits. And how learning anything from that zine that I mentioned and Kate Compton’s work it’s that like— And also this is just I think a well-known thing in the world, is that nothing can help you feel creative like a constraint and a limitation. And so, if you ask someone to make an artwork about anything, they won’t know where to start, but the more constraints and boxes and limitations you put them in, it’s like exerting pressure on one part of your brain and an idea pops out somewhere else. And so, physical materials have tons of constraints, and that makes them pleasurable and easy to be creative with.

And it’s not just about I think knowing where to start an idea, but I think that the constraints and limitations of the physical material…like for instance these are Perler beads. They’re these little plastic beads that you can melt together to make little little 2D artworks and stick them to windows. And they have a minimum resolution of like how big a single bead is. And once you’ve assembled them together, you can’t make anything more detailed, and you’re done. Like it’s a stopping point. And so, I think that materials’ limitations give you both creativity to start ideas, and it kind of tells you when to stop because they have a maximum resolution or capacity to be worked with. And so for instance this is a pottery wheel. And clay, when it’s been manipulated for a long time it starts to lose its strength and get floppy and fall apart. And so it means that if you are throwing pottery, you have to stop at a certain point. And that makes the creative process much more pleasurable because otherwise…it’s a hard part of making artwork.

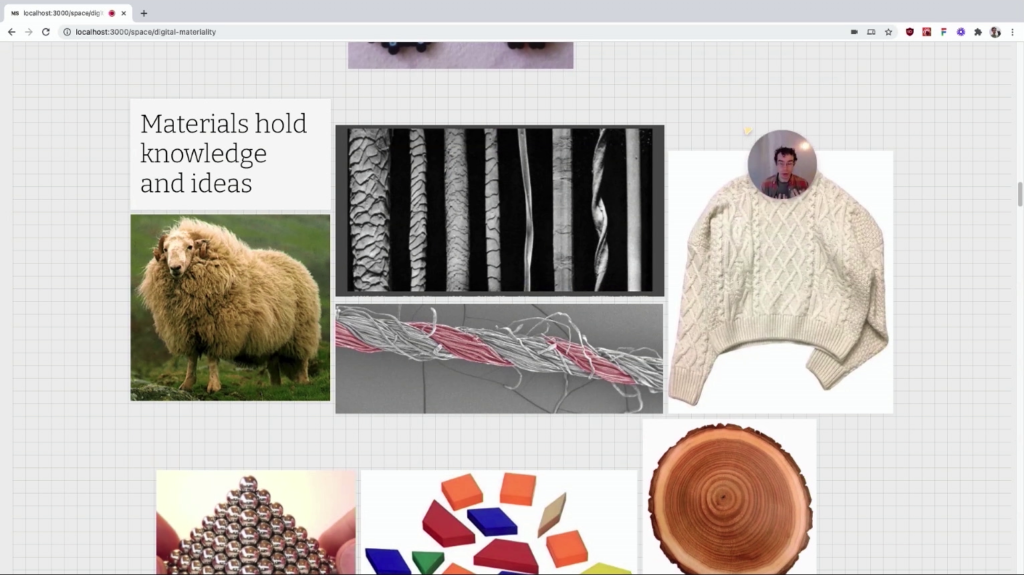

So I talked about the constraints, limitations. I think that maybe a little bit more esoterically, I think the materials hold their own knowledge and their own ideas. Especially it’s really evident I think if you look at natural materials. And so if you look at wood, or you look at wool, these exist as part of a living being and they fulfill a need for that being—keeping the sheep warm, keeping the sheep dry, as well as many other needs. And when you appropriate them into a piece of artwork or something, you’re taking on all those ideas and knowledge, and they benefit you—or they can work against you as well. But the wool holds information, I think. And I would say this even applies not only to natural materials but materials created by other people, and materials created by the natural world. They all kind of hold ideas.

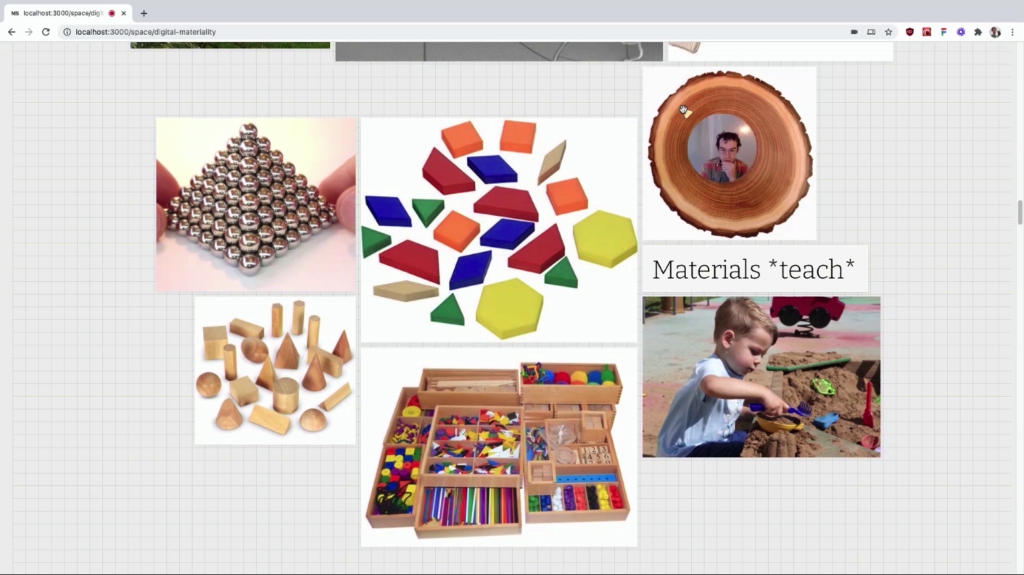

And those ideas influence… Like they don’t just influence I think the thing that you make with them. I think that the ideas also end up in your own head and they teach you. If you look at the world of like Montessori learning, or just the way that children naturally learn about the world and my personal favorite way to learn? It has to do with manipulating materials and using your own senses and your own…like, making theories about them, and you can learn so much about the world in this way. So I think that the ideas that can be expressed here are not just about oh yeah, color and shape, and understanding how to use your hands, but more complex conceptual things like a material can teach you about angles and repetition and tiling. And it’s not the same as reading a book where information is being kind of given to you in a rote way, but you’re creating the information on your own, with the aid of the materials that are given to you. And so someone did provide you with materials that they though would be helpful to you, and that’s I think the best thing that a learning environment can do. But you’re doing the teaching yourself with the material and the learning. And it’s not just for kids.

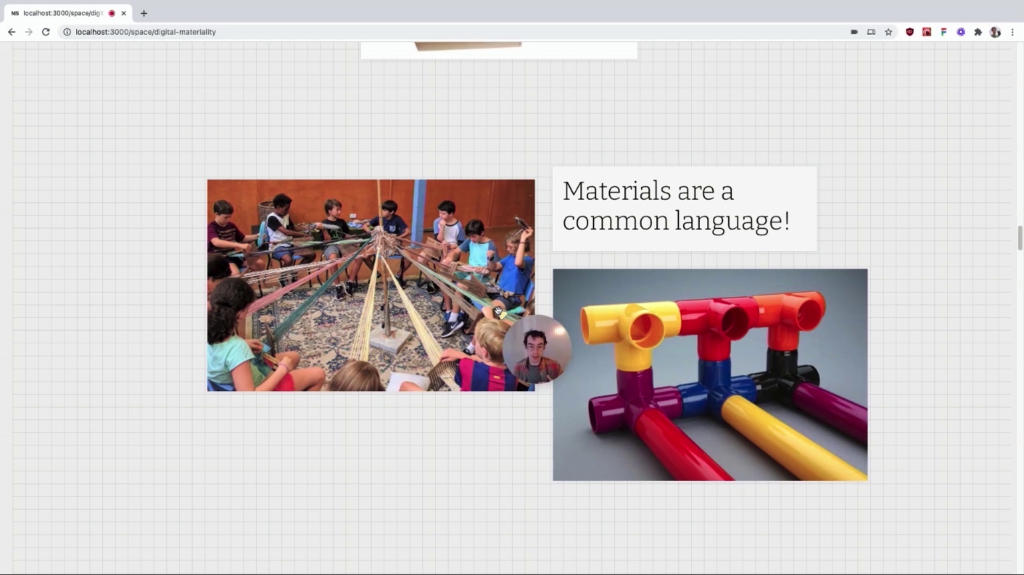

So moving on, I think that another thing materials accomplish is that they’re this common language? So the same way that I can have kind of a conversation with the world through a material, then this material is shared with someone else, they’re working with the same material, they have their own relationship. And now we kind of have a proxy relationship with each other because we both have a relationship with weaving or something, or with fiber, or with Lego.

And so this isn’t just like a social amazing thing that happens, but I think it’s also very pragmatic and practical, where if there’s a common material that has known ways that it behaves and compatibilities, like let’s say plumbing fittings, I could repair plumbing with different pieces that was installed by somebody who I never met thirty years ago, because they fit together in a certain way. It’s a physical language.

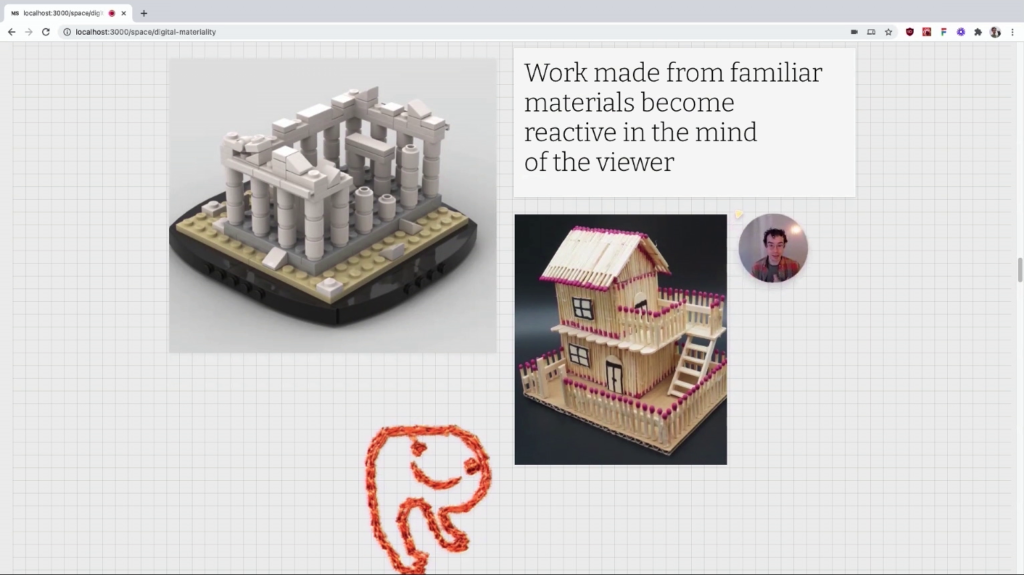

And I think that particularly when it comes to these familiar, everyday materials that people have relationships with, they take on this interactivity and this amazing…I don’t know, like mental reactivity? And so for instance this is just an image an Acropolis made of Lego, but if you have a relationship with Lego and you use them and touch them and you have experience in your mind, this image kind of becomes reactive, where you can imagine what it would be like to touch it and rearrange it, and maybe what it would feel like to put it in your mouth, or how it would break, or how it—what else you could make with these pieces. And this is I think something… The effects can be really strong. I think that’s it’s best with these common, everyday materials. Like this is a house made of matchsticks. And if you have a relationship with matchsticks and you’ve touched them before, you can kind of imagine would it would feel like to touch this house, and then also when you see something like this you can see in your mind’s eye what would happen. And so because this house is made of a material that you have a relationship with, you would have the extra depth of interactivity… And I call it interactivity with the artwork.

So that was a lot about physical materials. And I think that I kinda mentioned a little bit about digital materials and the idea of something being made of another digital object. And this is again this Japanese Excel artist, Tetsuo. And he actually was a retiree who wanted to start painting and thought that like… I don’t know, in an interview I watched he said that he thought that brushes and paints were too messy. And he already had a computer. And he said he was very stingy and didn’t want to pay for any other software? Which I like that story. He’s like, “Eh, I already have Excel and it’s good enough.”

And the material of Excel really affects not just like…you can see visually there’s certain motifs and textures and shapes that show up because it’s influenced the way that the drawing tools work in the Microsoft tool. But then also I think that yeah, it affects the way that we perceive this artwork as well. And also I think you can imagine, just looking at this image, the chaos of all these little boxes all over the screen selected and what would happen if you were to drag them or drag one of the little green buttons.

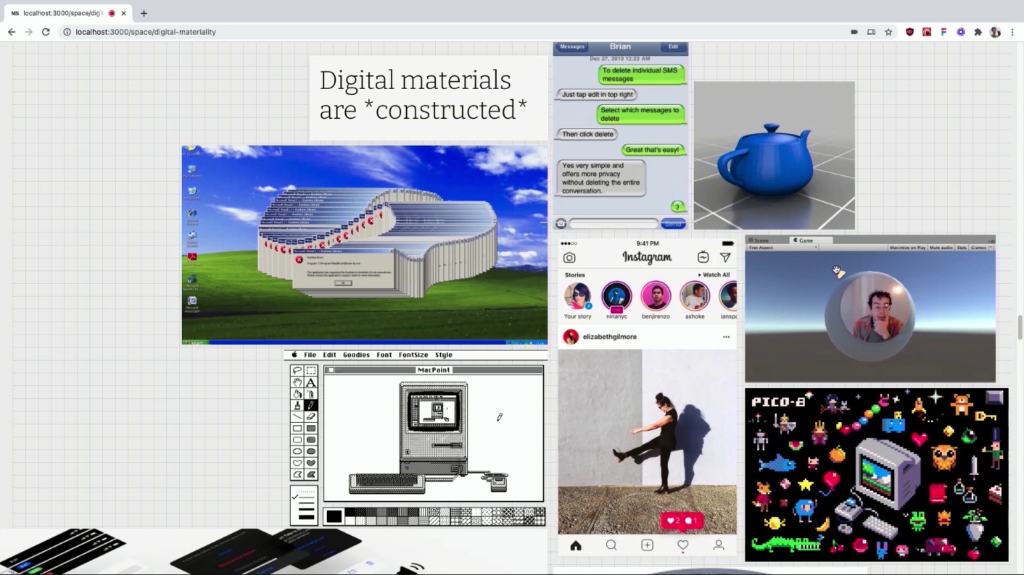

So, I think that another important property of digital materials beyond some of the other properties we talked about before is that digital materials are very much constructed. And so yes, physical materials can be constructed by humans. Like obvious Lego does not occur in the natural world. But in the digital work like, everything is constructed by people and in a relatively short amount of time, and is constructed also by companies. And so it’s a much more constructed landscape? And it means that when you’re working with digital materials, the intentions of a human are very close. Even if they’re hidden, they’re lurking. And they’re strong.

And so, I think that this can be a really beautiful thing? Like some digital materials are really designed with somebody was trying their best to help you create things, or to help themselves create things, then they shared it with everyone else. And maybe they have intentional constraints built in and intentional properties to help you accomplish something. But because they’re constructed by companies and— Like I consider Instagram to be a digital material, the way that it has little pieces you can assemble in different ways to produce different things of posts, and stories, and messages, and notifications. Like all those things can tell many different stories. And it is expressive, but it also has an agenda.

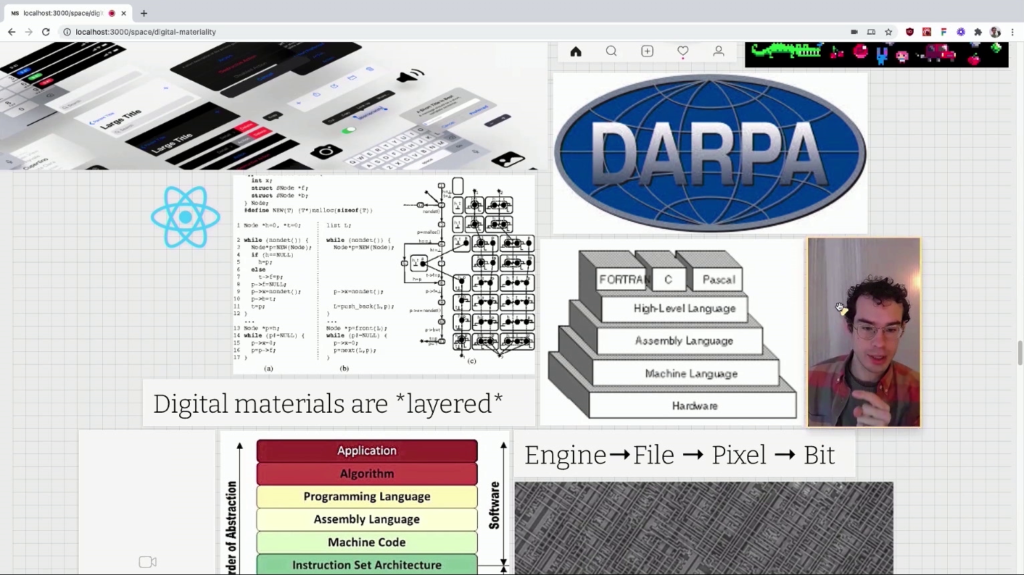

And so I think that in the world of digital materials, you are swallowing more of the environment around you and it’s worth being conscious of it, because… I think that digital materials themselves have a tendency to present as neutral, and to obscure that relationship that someone designed them with intentions besides your own. And so I think that one of the way that computing materials do obscure that relationship and that intention is the way that they are so deeply layered. And that’s the second property of digital materials that I think is worth adding on to the other things I mentioned before.

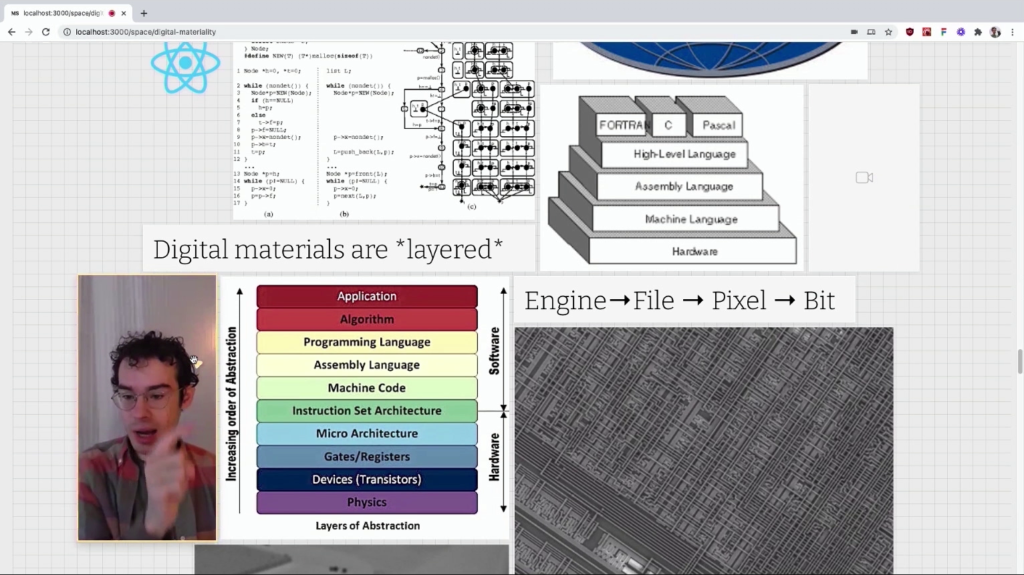

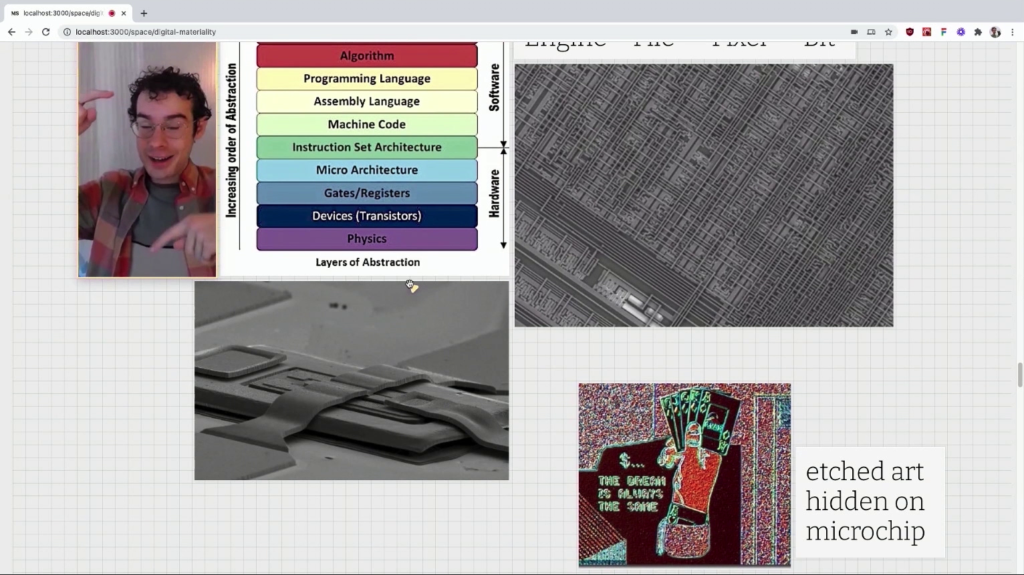

And so when I say “layered,” I mean that all materials are kind of made of other materials. Like I said wood is made of cellulose, is made of carbon, is made of atoms. Like the physical word has this hierarchy of materials being composed of other materials, but in the digital world those layers are very…there’s a lot of them, and they are very opaque. And so anything you make on a computer is going through many layers of—even just like, the programming language and then the machine code or the operating system, and the the hardware.

But in reality it can be a lot—you know, there’s many layers, and they’re kinda like history, or sediment. And it’s all very opaque to actually understand like where did this assumption or where did this idea come from? If I have a problem with the way computers work, was that idea encoded way down here [points at the “micro architecture” section of an illustration of layers of abstraction in a computer system] like in the 70s? And can I change it still? Like can I swap this out? Uh…it’s hard. And so there are many layers and it’s kind of opaque but it’s not like, infinitely layered. It does bottom out somewhere, and it can be understood. And so I think that maybe computers kind of sometimes don’t want you to ask these questions or don’t want you to look down here. But just because it’s opaque doesn’t mean its not knowable.

And so I think that I kind of mentioned like oh yes, maybe you’re making something in the material of a game engine. And that game engine is assembled out of files. And maybe those files are just an image file and so the pieces of the image file are little pixels. And the pixes are made of bits. And the bits are then themselves made of registers in different hardware, and that hardware is made of transistors, and those transistors are made of silicon. And so at the bottom, when all the layers go through, you connect back to the physical world, and I think that it’s worth considering that they’re not really completely separate worlds.

This is some artwork that was etched a couple nanometers wide onto some microchip in the 80s. I think it’s cool.

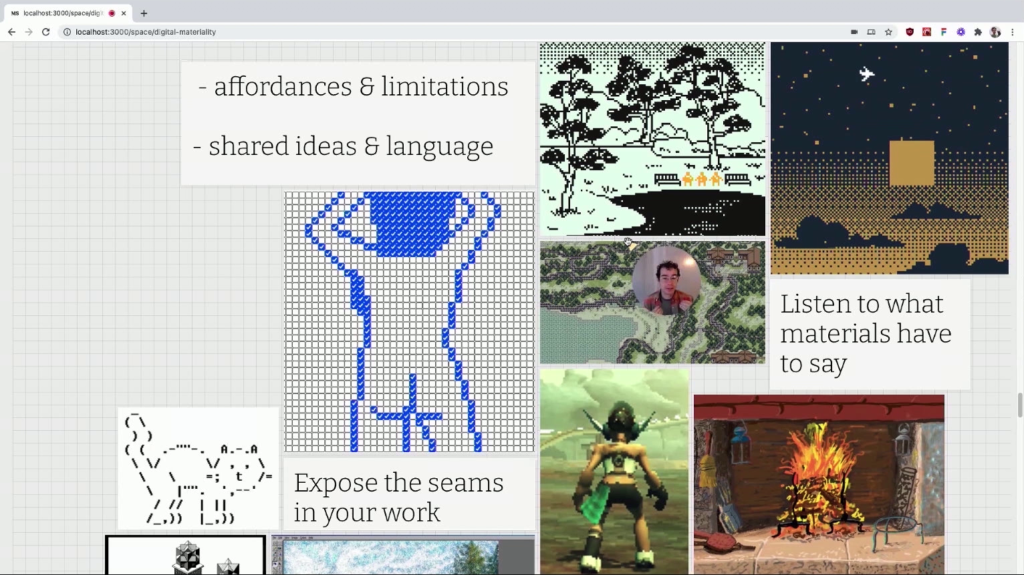

So I mentioned all of these cool properties that a digital material can lend to you artwork. And so they’ve got affordances of letting you build anything at all. They have limitations that kind of tell you when to stop or give you something to push against. They’re shared ideas that are kind of put by the creator into the material and that you can learn from. And that can express themselves in your own work, for better or for worse. And they’re also kind of a language of collaboration, where if you are… I think of like, open source is a community where people oftentimes are…the way that they related to each other is by sharing a material instead of actually talking person-to-person, but that connection can still be really meaningful.

And so I guess that I think that this is kind of like looking at the digital world and perceiving it through this idea of texture, and of what are the materials that compose something, and what are the properties that are coming from the material, and what are the properties that’re coming from the artist, and are those things in harmony, or what’s going on there is a really beautiful thing to do. And I think it’s a way to learn from the world. And I think that if you’re a creator, it’s good to listen to what your materials are telling you. And if they are pushing against a certain idea, or they’re pushing you down a certain path, it’s good to remember that yeah, material does have a say in what happens a little bit. And if it’s not saying what you want it to say, then you can maybe try to use a different material.

Maybe another kind of thing I would want to urge people to do is to expose the materials in your work and leave them visible? And oftentimes this is seen as like, amateur to…you know, you don’t want to use the default skybox in Unity because people will recognize it. But I think that by exposing what materials went into your work, it allows the viewer to experience it on that extra layer and to have a connection to the process, and to you. And so I think it’s a good thing to do.

Another thing is that I think that the power of a familiar material that people have their own relationships to, like for instance Minecraft blocks. If you can work with that material and that texture and express your idea with it, then you gain all of these other experiences that people have and all these other connections people have to the texture of Minecraft, and then maybe your sculpture can be mentally understood in all the extra ways. And I think that this can be subversive to work with familiar materials. It can just help people understand what you’re doing. And I think that this is something that can be really fun and exciting about…I don’t know, like digital mischief a little bit, sometimes.

And I guess finally that materials are constructed, and if you don’t like the materials that you have to work with in the world I think you can rearrange materials and make new ones and either compose new layers on existing ones or try to tell an alternate history of how materials could’ve evolved. And this can just be for yourself, of assembling kind of like a workbench of pieces that you like to use together. But it can also be for other people, and this can help other people create on the terms that they want to. And so I think that people talk about making tools and I think that maybe you should consider making materials that can be combined, with a different worldview.

So, that’s my kind of perspective on what a digital material is. And I really appreciate the chance to talk to you today. And yeah, I hope that’s interesting.

Golan Levin: Max, thank you so much. That’s wonderful. What a beautiful talk. We have maybe one minute for a question, and then we’ll wrap it up.

Who do you feel like your work is for? Who do you want to reach with your work?

And I should just say to everyone, Max’s work is intensely online and I encourage you all to check out— It’s at maxbittker.com, am I right? [Bittker nods] You can all see his many many projects, which are at your fingertips. But I“m curious who you hope or would like to reach with your work.

Max Bittker: Yeah. I mean, I um… When I was growing up, I had Internet access. But I couldn’t download or buy software. And so I spent lots of time playing Flash games and doing all the things you could do on the Internet that are free. And so that’s always the audience that I have in mind, is people who…maybe they have free time, they have an Internet connection, but they’re stuck somewhere or they’re bored or they don’t know about something. And I think that just by—there are so many beautiful things in the world that you won’t know about unless somebody gives you a book or you find it. And I think that just trying to package things that I love into a web site is to me—like that’s who I’m trying to… I’m trying to bring things that I think are cool to people who have a browser, I guess.

Levin: That’s awesome. Terrific, thank you. I’m sure there’s going to be more questions for you over in the Discord. And to those of you who are online, if you are not registered with Art && Code, if you go to artandcode.com/homemade you can register for our conference and that will give you access to the Discord channel where you can have conversations with our speakers and everyone else in the community who’s following along and chatting.

With that we’re going to take a break for a couple of minutes. And then we will pick it up again at 10:30 with LaJuné McMillian. See you all soon. Thanks, everyone. Thanks, Max.