Golan Levin: And we’re back. Welcome back, everyone, to our second talk of the morning of Art && Code: Homemade. And it’s my terrific pleasure to introduce Lee Wilkins, who is an artist, cyborg, and researcher, and community organizer interested in technological curiosities and the creation of whimsical robots. Lee is a doctoral student at the University of Toronto, and teaches wearable technology, physical computing, and new media arts and design at OCAD University and Ryerson University. They’re also co-executive director at Little Dada, a group of creative technologists for social change, and community manager for hackaday.io. Folks, Lee Wilkins.

Lee Wilkins: Thank you so much, Golan. I am so excited to be here. And this is a particularly really interesting format as well because I feel like all of these talks feel really intimate because I’m just sitting in my home as opposed to sitting in this conference environment. So I feel like listening to everything before me I’ve taken a lot of it very much to heart more than I would’ve otherwise. So, thank you so much for putting all this together, Bill and Golan and the whole team.

So, just quickly about myself. I feel like I generally wear a lot of hats. I’m not really sure exactly who I am or what I do but I think I’m all of these different things. I tend to sort of bounce, really, back and forth between these different identities. You know, at some point I really heavily identified as an e‑textile practitioner, but I think you’ll see in my work it’s strayed quite a bit from that.

I do a lot of community organization. I really love getting people excited about making weird technology. I also have a day job in experimental hosiery manufacturing, which is largely unrelated to anything I’m gonna talk about here but, we all have day jobs.

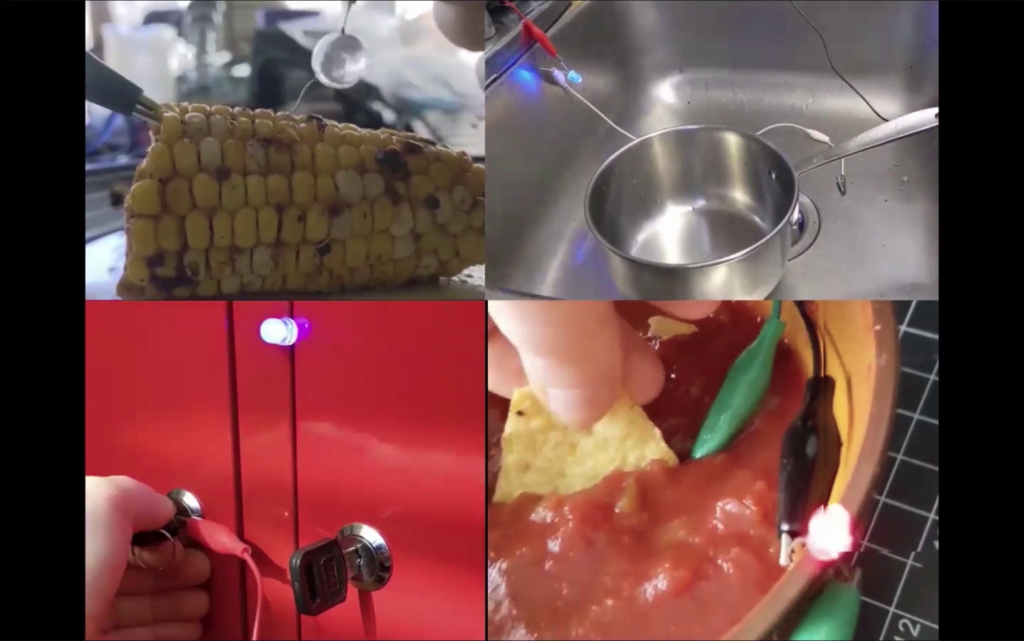

The stuff that I’m really interested in, you know, is stuff like this. This is a project that I was working on throughout quarantine. So it sort of explores the environment around us. And it’s also something I’m really thinking about a lot as we go into this next semester of teaching and teaching online. Thinking about how people can explore the spaces around them and make technology out of something that we normally wouldn’t have thought of as technology. I feel like it’s an idea I’ve kind of been peddling for a long time, but one of for me the interesting things about being confined to my own space is I’m forced to reconsider it again and again in all of these different kinds of ways.

But really what my work is concerned about is the body and technology. And through watching a lot of the folks present this weekend I feel like I’m definitely on the same brainwave as a lot of folks here. You know, they’re often thought of as very different things. Technology is thought of in these sort of rigid forms and devices, and the body is like this organic other type deal. So, I’m really about exploring the tension between those things.

This is a project I worked on for the last couple of years called Voids. And it’s actually just a very simple sort of light trick. A lot of my projects you’ll see use really simple technology to try to maximize those kinds of results. And this project is kind of… I mean, to be really honest I really like the idea of putting your head in stuff. I think that’s a really fun thing to do. A lot of my work in the past few years has really been revolving around your head and your face and all of the things that you can do with it.

So basically what happens here is when one set of lights is on, the person whose head is inside one of the trapezoids can see the other person, but the other person can only see a reflection of themselves. And then it sort of switches back and forth. So while you’re watching someone else, they don’t know they’re being watched and they’re watching themselves. And yeah, it’s just a really simple kind of light trick. It uses the same reflective coatings that are on buildings on windows. So there’s no real magic here, but I was super fascinated by the material and also the fact that it’s kind of this everyday material that we really don’t kind of think about. We sort of just take these buildings almost for granted. And I really like the way it kind of changes your perception of space and sort of throws it back and forth. So it’s almost like a conversation between these two different people in terms of perspective and it sort of being constantly thrown back and forth.

So this type of work has sort of led me to this big question about what is a body, and where do the boundaries of your body end. And this is where I’m doing my PhD research and I could spend a long time talking to you guys about materialist theory. But I’m not gonna do that here, I just want to show you guys some cool art.

But, basically one thing I’ve been thinking about a lot is just like, what do we consider to be our body, and what have we kind of agreed upon? Are we thinking about the microbes that are all over us? Are we thinking about what happens if we get cut and bleed. Like, where things start to and stop becoming your body?

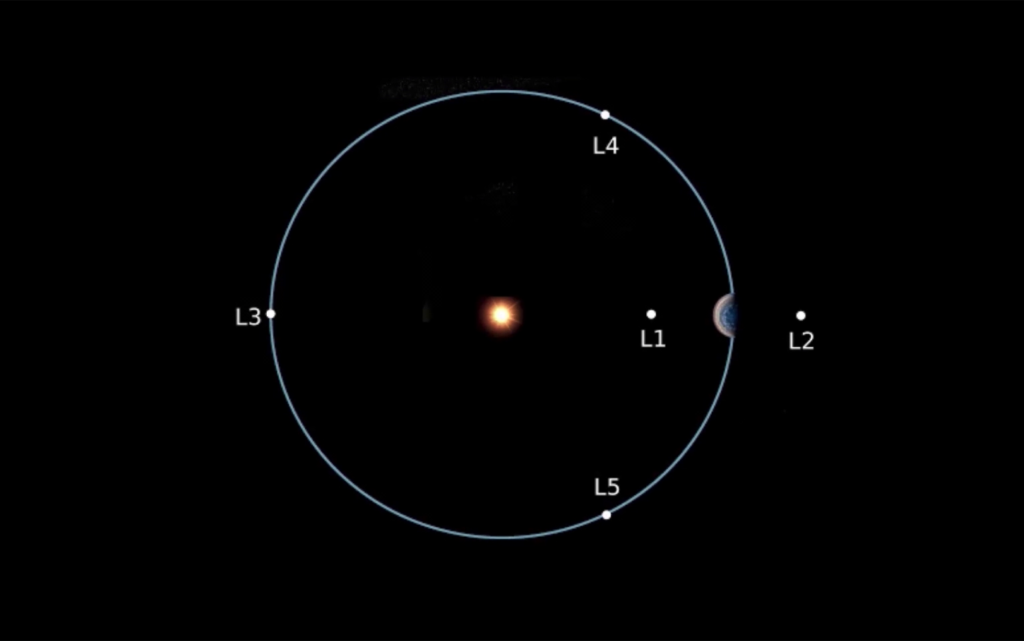

And one area I found that was really interesting or a way of thinking about this is by using space settlements. So space settlements in the last few years have become sort of a central touchpoint to my research. And every time I do a research project, I imagine it in my imaginary space station L4. So, during the 70s—some of you might be already aware of this—there was a really big movement of sort of utopias and imagining all these different environments that we could live in. And the L5 Society was a group of folks who were super enthusiastic about the idea of a space settlement in a point called Lagrange 5.

So what we can see here is sort of a map of the Earth and the sun. And these labeled points are called Lagrange points. And they are basically points of gravitational equilibrium. So if you put an object in between…for example we have L1, which is right between the sun and the Earth, that object will stay in gravitational equilibrium. And it’s the same for all of those points. They each have sort of slightly different effects. But the L5 Society was imagining this space station at Lagrange 5.

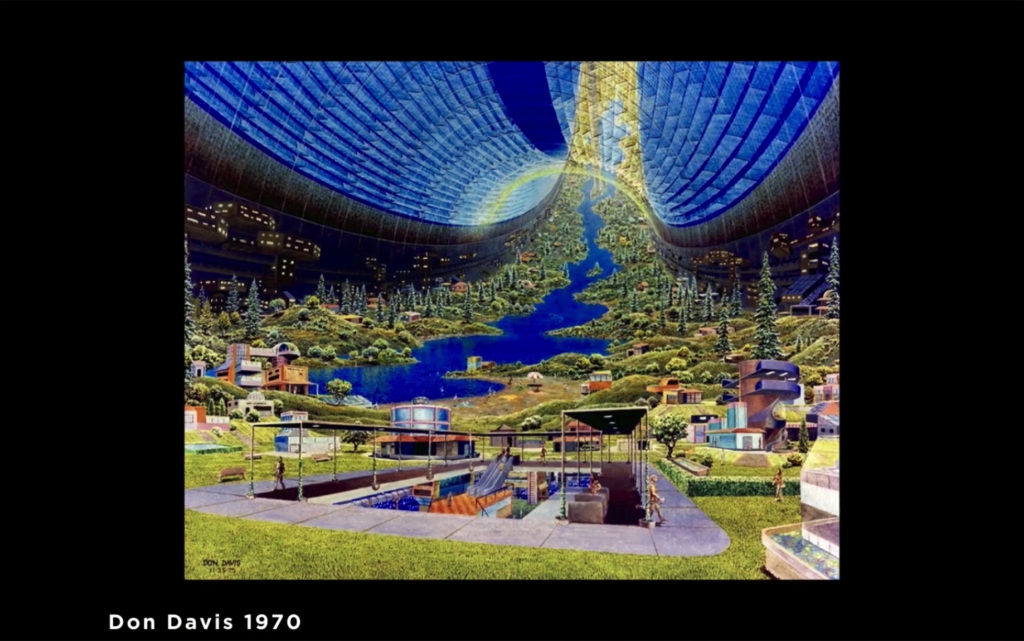

And there’s a whole bunch of really interesting art sort of about what these space stations would look like and what kind of form they would take. So this is Don Davis, and it’s a piece that illustrates the Stanford Torus space station, or space settlement. And what I like to think of this is like status quo space. A lot of these space settlements sort of extrapolate on the way we have technology already and sort of put it into space. And you know, these very, like, normative ideas that we can pretty clearly digest. Like okay, so it’s kinda like Earth but it’s space.

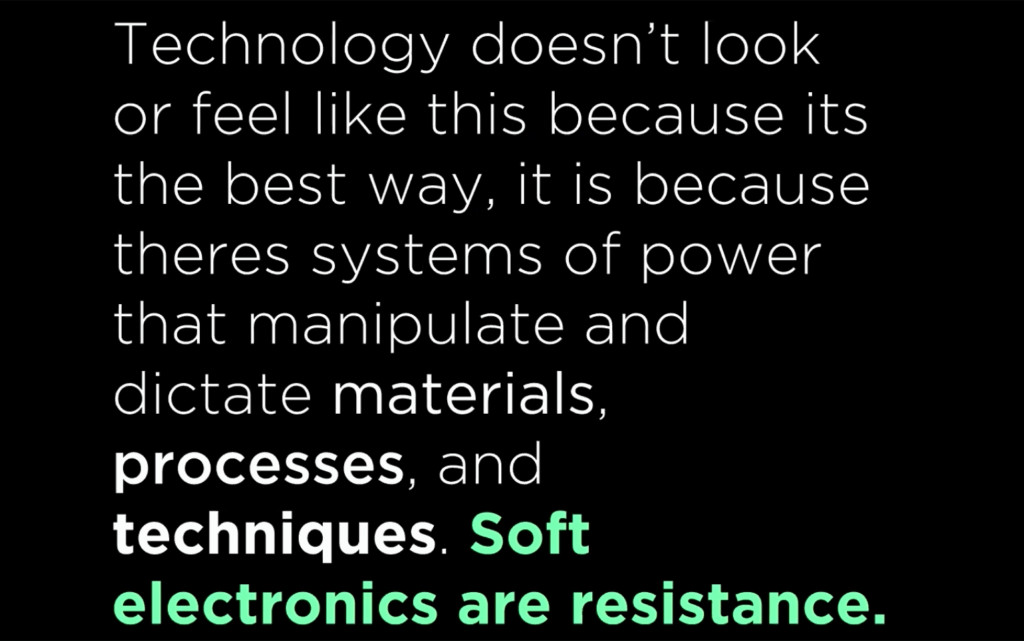

So, I think this idea is super super interesting. But the way I think of technology…you know, the way I’m trying to get people to think of that stuff differently, is that things aren’t always the way they are because that’s the best way. But they’re sort of embedded in these ideas of power and process. And that’s why I like to think of e‑textiles, and soft electronics, and weird electronics as like a way of resistance. I mean resistance in partially a political sense but also in resistance because often these materials…are quite resistive.

So what I started doing I was working with some friends to imagine L4. So L4 is kind of like the equal and opposite point of L5. So, mathematically they’re the same. You could also put a space settlement in L4. But in our L4 society, we are…you know, this like, speculative feminist space station. And we curated—myself and Hillary Predko, and also Sagan Yee—we curated work from a bunch of different folks to imagine what life would be like on L4. So this is a zine that you can read online and have a look at what these different folks contributed. But also it’s just sort of like— I try to present all of my current work as though they’re operating in this station that is sort of opposite this normative idea of space stations. So, it’s like at an equal and opposite kind of floating point. And what would those technologies look like, and what would those technologies kind of feel like.

I’m really interested in the idea of space stations because it inherently means blurring the boundaries between us and our technology. We’re breathing in the synthesized air, we are existing in this environment where everything has to be kind of curated. So it’s really like, so viscerally about bodies? that yeah, I’m totally fascinated by these ideas.

So, in order to start bringing these two things closer I’ve sort of divided up some work I’ve been doing into three sort of touchstones. The first one I’m gonna talk about is bringing the human to technology. So, taking what we classify as like human feelings or human ideas and putting them onto this like cold idea of technology. So, this is something that I think has been you know…it exists in a commercial sense. Of course none of the things I’m going to show you have quite the market value that we might want but yeah.

The first one I’m gonna show you is this idea of what it would look like if a server room got married. So thinking of these two very disjointed kind of ideas and sort of smashing them together. So this is a piece that I worked on with my collaborator Hillary Predko, and it’s a drone dress. It sort of takes these ideas of like drones, and servers, and hard technology and sort of pairs it with high fashion. So, this was a part of Make Fashion 2018. It’s a runaway piece, so existing in a very high-fashion environment. But basically there’s this drone that sort of follows the model down the runway. And her garment is made out of Ethernet cables and there’s industrial fans on her hips. And you know, it creates this actually quite elegant output. And we sort of selected the most bro-iest of technologies like drones and Ethernet cables and sort of smashed them together in a sort of high-fashion wedding dress. So yeah, that’s sort of part of this exploration that I’m going for.

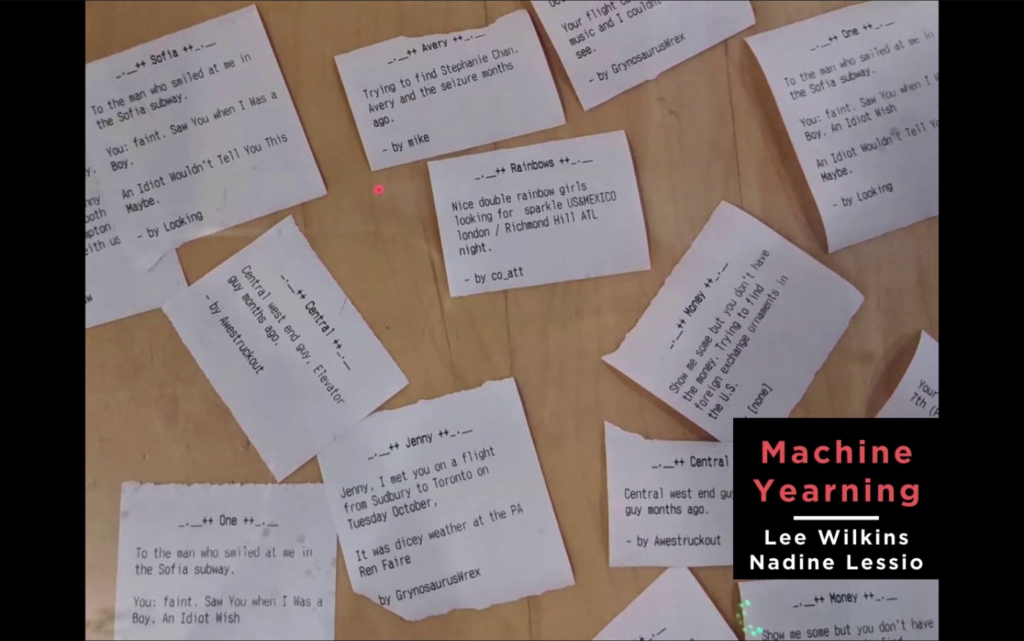

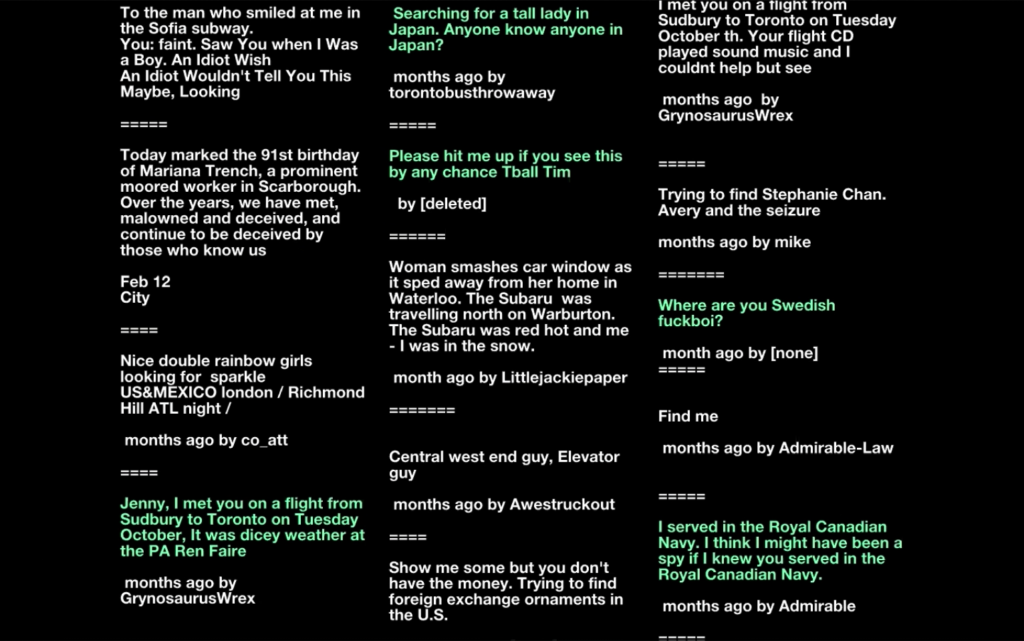

This is another project that I worked on actually just as the last thing I did before the pandemic hit. This is called Machine Yearning. So it’s a pretty basic machine learning project. And it’s just sort of about ways we can see the machine kind of reaching back to us.

So basically it is a whole bunch of personal ads. And we took them from local Toronto ads, because we made this in Toronto. And we sort of put them through a machine learning algorithm and tried to have it spit out what the machine really wants and tried to pull that sense of desire. I’ve highlighted some of my favorites here. I really really like them because it kind of takes all of these different types of yearning and puts them together like the machine is really fighting to try to find what it wants, or trying to find that similarity. But yeah, it prints them out on little printer receipts, which again feels like this very formal way of presenting this idea of yearning.

So yeah, that’s sort of like the ways I’ve been trying to make the technology more human. But then bringing the technology over to the human side I think is another interesting thing that I’ve been kind of exploring. Like I was really thinking about what hannah perner-wilson said yesterday about the idea of falling in and out of love with e‑textiles. Definitely can identify with that. I feel like… Yeah, things have changed. So when I was thinking about my e‑textile practice, I was thinking well what is it about the practice that I really find interesting. And I think what I really find interesting is the idea of finding affordances using the body and also like being physically very flexible and pliable and trying to make technology into these organic kind of forms.

So this is a couple of experiments I was working on sort of using my face as the platform of the interface. So, they’re all super basic. They’re all just switches that’re made with conductive tape. And they sort of use the elements that already exist, of course on my face or things that I’m already doing, to create these small elements of interaction. So, with this I’m sort of trying to imagine what it would look like as a full-body interface that you don’t really have to think about your interaction with technology, you don’t really have to think about engaging with it. It sort of comes about as a result of your existence within the world, right. So what does this look like when the technology starts to become part of us? We don’t have to think about like pressing this button. We can just sort of interact with our bodies in this way.

So of course all of these are just you know, some tape, some alligator clips, and some LEDs. But what I really want to do with this is prompt ways we can think about engaging with the body and using it to control other things or engage with things in another way.

And then the third kind of deal is creating this like, blurring the boundary a little bit more deliberately. So once we’re at that point, how can we start to almost forget when…you know, forget that one is the other. And I’ve taken a couple of stabs at this over a lot of different types of projects. And I don’t think I’ve quite seamlessly merged the human and the machine yet but…you know, working towards it.

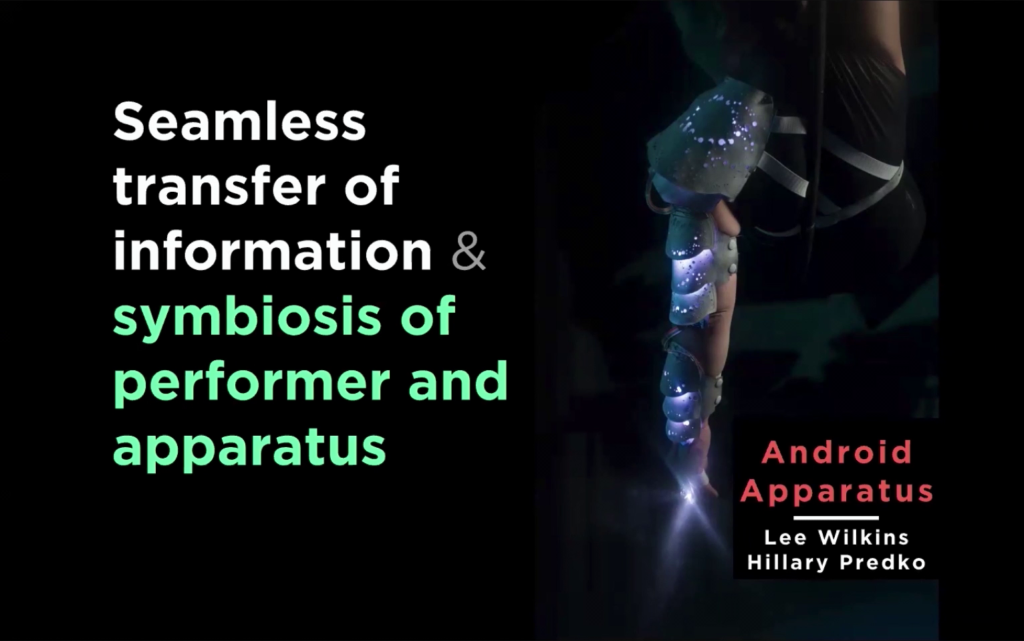

So this is a piece called Android Apparatus, and it’s sort of about the symbiosis of a performer and apparatus. So how these two objects you can be fully intertwined together and create a reciprocal interaction.

So, this is a circus performer piece, and basically the wearer is on a lyra, so it’s a suspended hoop, and she does a performance. The piece is designed— We put a bunch of sensors all over the artist and we had her do this specific dancing. And we used that data that we got to create this garment. So we looked at what areas of her body in this dance she uses to touch the hoop. We looked at how he’s physically moving, how many times she spun around. And we used that to physically design the garment. So the patterns on it are the data from the dance, and the location of everything is based on exactly how she’s moving. And as she moves it changes the lights on the garment. So we’re trying to sort of create this thing where in order for the garment to exist in its full beauty, it requires to be used in this very specific way. And in order for the performance to exist in its full beauty it requires the use of the garment. So it’s creating this almost symbiosis.

This is another piece that I worked on at Dinacon last year. And it is about collaborative sensing. So, it’s a sensor that can hear bat noises. So, normally we can’t really hear them with our human years. We aren’t capable of receiving that high frequency. So basically one person has a sensor on their hand, and they are able to point it in various directions and try to find these noises of the bat. And the other person has a transducer on their head. So, a transducer’s a bone-conducting sensor so only they can hear the output. But these two people…you know, individually they can’t hear the bat, but when they touch hands they complete their circuit. So they have to sort of walk together through the jungle and find these bats and listen together and it creates like a collaborative kind of experience.

So in this sort of way we’re sort of blurring what it is to have this singular experience and it becomes this group experience of walking together and being together. And… Yeah, so that’s what I’m kind of trying to do here, is figure out how we can—if we can expand the sense of one sort of engagement.

So I thought I’d take a couple minutes to talk about my next steps. I have been really thinking about what else I could do to create this blurring of environments and blurring of interactions. And again, during quarantine I’ve become very very interested in this idea of fishtanks, mostly for a hobby. You can see my fishtank over here. And I’ve been really thinking about what that’s almost like for the fish. They’re almost like creating a space station for the fish to exist. I’m really into the idea of like filterless tanks that are really self-sustaining. So I was sort of thinking about how I could have the fish experience this idea of L4, or this idea of the space station.

So what I’m gonna do next is I’m in the process of building a shrimp space station. It’s going to be a wearable garment that allows the shrimp to experience the outside and are almost going to be… It’s going to be like a wearable device, that I’ll have to take shrimp out so they can get their UV light and be happy in their environment. But also it provides this fully-sustaining system for them to live. So yeah, that’s what I’m really excited about next. I’m really excited to try to make some wearable shrimp space stations.

So that’s about it. That’s kind of all I have to talk about. I’m happy to take questions. If you want to get a hold of me you can find me at @Leeborg_. And yeah, thank you so much.

Golan Levin: Lee, thank you so much for this incredible presentation. Lots of great comments in the chat. I personally love the idea of mounting things on one’s head as a mode of artistic practice.

Got a bunch of quick questions for you. What’s a new sense you’ve been hankering for personally?

Lee Wilkins: A new sense. Hm. I’m not really too sure. I have a couple of implants. So I have like a magnetic implant. However I feel like it’s not maybe necessarily everything it’s kinda cracked up to be. So I’ve been really interested in kind of exploring other implantable senses or ways to augment that and make it—yeah, like a little bit more of a way of perceiving the world as opposed to just a cool party trick where I can pick up small Canadian change.

Levin: Mm. So this question is more sort of—goes to the philosophy of what you’re doing. I really appreciate how your work spans both sort of performative augmentations of the body that are almost like fashion or you know, for other people to kind of display. That there’s a kind of a public face to it. As well as very private things like you know, putting a magnet in your body and things that aren’t obvious to others and which enhance your own sensorium. Do you feel like— This is the question. Do you feel like you’re prototyping for a future you want to see, or do you feel like these works are set in the present and are asking people to reflect on their current relationships with technology?

Wilkins: Yeah, that’s a great question. Definitely when I situate my work within L4, it’s very future-focused. But I also don’t think you can like, snap your fingers and make a different future, right. We have to critically think about why we think about technology the way we do, and we have to critically think about why you think one thing is technology and another thing is not. Especially like the earlier slides I was showing all the food switches and stuff I made, you know. Like, I’m not necessarily saying that we should always use corn as an interface for things, but I am saying we should think about why we don’t. So…I’m not sure if that answers that but maybe.

Levin: Yeah. Sure we’re saying both, and it makes sense that we have to kind of prototype it to get there.

This is a question from Lea, which is “How do we think about wearable performance garments that move away from reactive or visualization roles and into interactivity or with its own agency? In other words, how do we meld performance to unpredictability?” Thinking about performance garments.

Wilkins: Yeah. Totally. I really—you know, I’ve been thinking so much about agency in like the philosophic sense. So how we can allow objects to interact on their own without any of this like human-type interference. And I’ve been thinking a lot about thermoreactive garments and those types of atmospheric-reactive garments to try to create that sense of agency that these things on us are enacting around us and not because of us. And I think that’s a really interesting idea that has definitely been swirling around in my head.

Levin: And a final question, because we have a moment, which is, you also make zines. And I’m curious if you could talk about how or whether or to what extent that plays into your creative practice. Is it a mode of publication or do you actually see a much more tight material connection in terms of giving things to people?

Wilkins: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I started making— I have a couple of zines—I could drop it in the chat—about about wires, LEDs, and buttons. And these are three things that I feel like are often really overlooked in the electronics world of like “Oh, just connect it with a wire” and there’s so much small knowledge there and very tiny facts that it’s really hard to get a handle on. So I really wanted a way for people to be able to get that information without feeling overwhelmed or like it’s super technical.

So I feel like zines are super…they’re an approachable way. You kinda like, pick one up when you’re waiting for an appointment or waiting at a maker space or whatever. So it gives people this kind of casual way to absorb that detailed information. Like I just keep thinking back to when I was learning electronics and I first stripped a wire that was multistrand. And I was so confused because I thought that all wires were solid core and nobody had ever told me. And it’s just little moments like that that I want people to have an accessible way to understand. So, that’s sort of my motivation behind the zines.

Levin: Got a question from Kate Hartman. And we have basically one minute left, we’ll see if we can throw this one at you. “How do your art practice, community organizing, teaching, and doctoral research interact and intersect with each other? Or do you see them separately?”

Wilkins: Yeah, I feel like it’s always…they’re always swirling together and always influencing each other. So for example like somehow L4 has now made it into my dissertation, but also I’ve run community events with it, so it’s impossible to keep them one out of the other. I feel like they are…yeah, they’re always, always self-influencing. And sometimes that could be helpful but sometimes…[laughs]…sometimes it builds on itself a lot.