Golan Levin: We’re back. Welcome everyone to the final presentation of our morning session here at Art && Code. We do have two more sessions this afternoon and evening of Saturday. And it’s my terrific pleasure to now introduce Laura Devendorf, who is an artist, researcher, and professor in the ATLAS Institute and the Department of Information Science at the University of Colorado, Boulder, where she directs the Unstable Design Lab. Her work presents alternative understandings of technology that draw heavily from feminist technoscience, trading notions of efficiency for engagement, control for humility, and individualism for cooperation and care. Laura Devendorf.

Laura Devendorf: Thank you, Golan. And thank you to everyone who’s spoken so far, and for the amazing talks and inspiration, and for those who gave me this opportunity to share some things with you.

So hello. I’m Laura. I have something planned for today. I’ve had the benefit of watching other people’s talks and I’ve been liking this idea of something that’s a little closer to a show and tell. And so, part of my research is really rooted in my own experience, and maybe a good way of explaining it— Oh. Hey Frankie. You wanna come sit with me?

There’s a lot of things like tiny people, like this one. [swivels camera down to show her child, who howls]

So yeah. I wanted to share this as very much coming from the home. There’s a program called Artist Residency in Motherhood that was started by an artist named Lenka Clayton, and I’ve always taken that as inspiration in really kind of trying to find ways to make my home part of my research.

Anyway, I’m starting in the kids’ room, so maybe that’s why we’re also being interrupted. This is the room in our house that we call the art room. It’s very messy, just like most of my house. And what I’m going to do is I’m going to show you a few different objects. Some that I find inspirational and some that I’ve made. And the theme for this talk is really about delight. And so it’s about kind of finding delight in objects and the way that objects form us both physically, the way they support us physically, the way our bodies support human and nonhuman bodies. And also what that kind of experience of delight or joy is. And as I’m gonna show you things, I want to sort of emphasize that it’s not just like a no-cost thrill. It comes from struggle, and endurance, and staying with something in labor. And so, the different things I try to build try to mix those two up.

So, the first thing I want to show you is a toy I used to play with as a child. And this is called the Quercetti. It’s an Italian company, I believe. They still make these. And it’s called the Mosaic Machine. And what this object is doing is it has all these colored balls. You tip them noisily up to the top. And then you have to sort of…you sort of select where those balls go by pushing these buttons. And if you don’t want many of the colors, you go over here and you can scan through them.

So I wanted to start with a simple idea, just because it’s sort of showing this like…the joy of organizing. The joy of knowing that every ball has a place. And how in so many aspects of our design and life we’re seeking that kind of certainty. Or that’s what I feel, anyway. I mean, that’s a lot of the reason I love code, is because it kind of offers me that sense of control and that sense of certainty.

The second aspect of this that I’m going to kind of come back to is how it’s not this kind of grand creative gesture like the blank canvas and the paint. It’s really the joy of pressing buttons and doing a kind of operation. And so I’m going to fast-forward now about…let’s see, I was about 8 when I was playing this. I was about 28 when I got my PhD. So I’m gonna fast-forward about twenty years to a project that I did when I was a PhD student at Berkeley. So let me just go ahead and share my screen. There is no sound.

https://vimeo.com/145324024#t=75s

This is a project that I worked on called Being the Machine. And Being the Machine was this idea of being able to sort of create with 3D models, but not having to have a 3D printer create those models for you. So, I’ve always been interested in code and creative coding and computer science. And I really liked learning about computational geometry and making 3D models. But I hated the fact that I had to give my models to a 3D printer to make, and I wanted to make them by hand.

And so I devised this little system, which is just a pan/tilt bracket with a laser pointer on it, that basically draws G‑code. And you follow the G‑code by hand. So you can see here that I’m actually doing that with clay.

And so, over time you can take this wherever you want. I’ve built with pancakes, with balloons, with different…who knows what, Cheez Whiz, glitter, lots of pipe cleaners. And what I liked about this project was thinking about creative action not so much as again this grand blank slate thing, but just the kind of ritual performing of a gesture, of becoming the machine. And then when you sort of take on that role, it ends up heightening different sensory experiences you have. So, the dissertation I wrote was very much about how you learn about the agency of materials when you’re working with them by hand. And how the materials come to form the maker. And that the ideas actually really come from the materials, rather than us having ideas and putting them in the materials.

So. I’m gonna keep this playing for a little bit while I walk us downstairs, where we’re going to continue the rest of the talk. Actually, maybe I’ll stop sharing so you can see a little bit more of my studio/work space. Which, you know…is also my house.

So. We’re the children’s art room. We’re walking through the hallway. We’re saying hello to my husband August. Hello.

I actually got the old 3D printing system out. So maybe while we’re going down you can look at the simple little pan/tilt bracket. I believe all the instructions are still on Instructables. Costs about…I don’t know, twenty dollars to make this? Although when you work at Autodesk you have the sort of insane privilege of really intense 3D printers. So there might need to be some kind of finagling to get it to work on different printers. But luckily they also just sell pan/tilt brackets.

Okay. So, we are getting set up in my basement.

So. We’ve headed downstairs and now we are in the place that’s been my studio for the past year. And this has become my new sort of mechanical muse. It is a hand loom. And it’s called a Baby Wolf. It’s a floor loom. And what I really love about this is that it’s kind of taking so many of those ideas that were in that original toy and in Being the Machine, and it already exists in a machine, which is a loom.

So a loom is actually just lots of threads that’re threaded perpendicularly. And the way you thread them through the different frames determines the pattern. And so what you actually do is do something kind of like assembly programming, where you wire up your pattern into these different frames, and then you use these foot pedals down here… Let’s see if I can get it closer to the foot pedals—hello, feet pedals—that’re down here. And that actually lifts up the frames and allows you to throw the different patterns through.

So, weaving has been so interesting because it’s like you get to program. And you do get to program in a lot of different ways. But then, you get to have all the discretion of like, which G‑code instruction you execute at any given time. And you get to play with all these different materials, which is really really fun.

So some of the materials that I’ve been using that are my favorites are materials like this. Which is actually just paper. It’s kind of like a wax paper. It’s really crunchy, so that when you weave something with it it’s not just about having something wearable so much as a whole sensory—it makes sound, it has a feel against your body.

And in weaving there’s all these kind of cool different structures. So I’ll show you this one. You’re not even just weaving flat sheets, right. It’s not all about dishcloths. But what I’m finding really interesting is there’s this… I don’t know, before written history people have been weaving. And there’s thousands and thousands of years of knowledge in the different structures for weaving, many of which aren’t just flat, they’re multilayered.

So in this example you can see here I’ve woven three layers at once. And so I can actually pull them back layer by layer and I can create these really integrated systems. And some of the systems I’m making as part of my research are essentially just multilayered circuit boards. So they’re kind of like woven circuit boards.

So in this example I just showed you, this is a 2D position sensor.

So, on the bottom layer there is a really conductive copper yarn. Actually it’s the same yarn hannah showed in her talk the other day. Then the middle layer is this kind of separating mesh. And then the top layer is just one continuous strand of resistive yarn.

So in that sense you kind of weave it all at once, and then afterwards you do a little sewing and mending. And it all comes together. And what’s really kind of fun is that then I can also just weave in things like the voltage dividers, and the power and ground rails and things like that.

One of the things that I may be most excited about about weaving is that this entire circuit didn’t use any adhesives. And so, this is an entirely disassemblable structure. So some of the research I’m doing with my graduate student Shanel Wu is really thinking about how we can use design software to build in disassembly and the ability to mend, from design time. So instead of being like “Oh, wouldn’t that be a nice thing to offer,” really building that in as a core functionality.

So, now you have been exposed to my love of looms and my love of weaving. And I have lots of other things in here. But now I’m actually gonna shift over and talk about the second facet of weaving that I’ve also really loved.

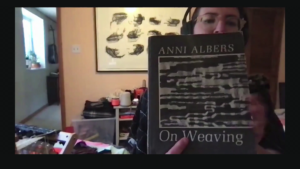

So I sort of compiled a whole bunch of books. This one’s not about weaving. Let me get to the ones that I want to show you. So. Weaving also combines my love for control and programming. Because to make any woven structure, you use something that’s called a draft.

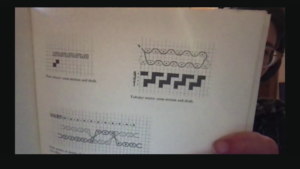

So this is a very famous…if you want to learn to weave, this is kind of like your bible. Or whatever religious text is very meaningful to you. Or not. And Anni Albers has this really beautiful way of drawing the woven structures. And so she draws the drafts, which show basically which yarns go over and under others. But then she also shows you kind of from a cross-sectional view what structure that makes in the fabric. And just this process of even drawing them is really therapeutic. And so that’s actually what I’ve included in the zine. It’s sort of a quick instruction of how to write drafts and how to draw them by hand.

It also means that when you go to thrift stores you can find any number of craft books. So like this one. Some of my other favorites—when you are interested in fiber art you get a lot of spiral-bound books. And I just love this idea that there’s been this thriving community of people. It’s kind of like a zine community but it’s really focused on technique. And they’re all over the place. And they’re very affordable.

This one is about a technique called marbling, and what I love about it is there’s an inscription on the front that says “The best part of learning to marble was finding a friend in you.” And so, I don’t know. There’s a sweetness to finding these things that’ve been owned by other hands, and knowing that you’re kind of carrying on those different techniques.

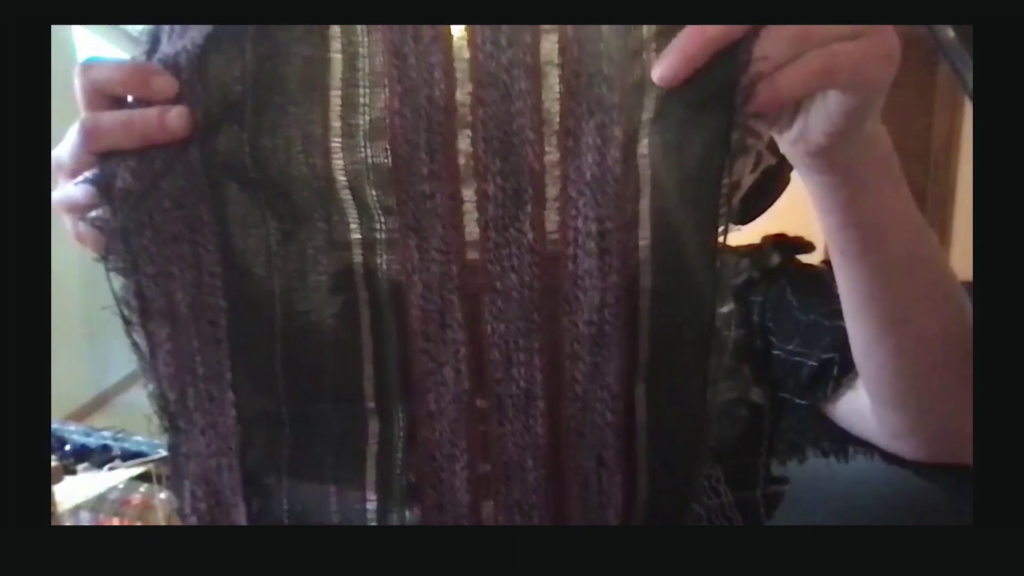

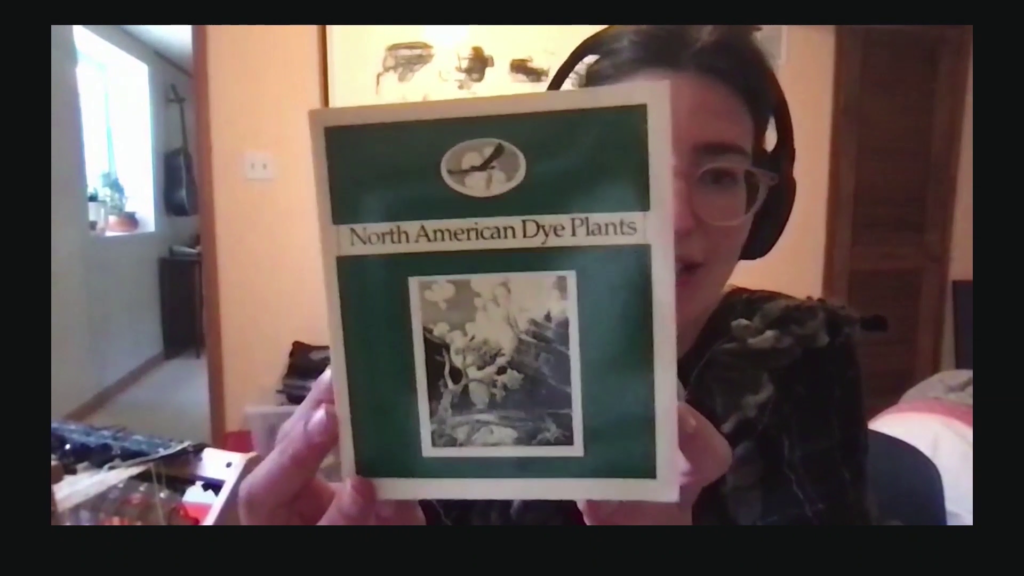

The other thing I like about weaving as it becomes a natural exploration. So, all these plants around us, I didn’t realize that milkweed that grows in my neighborhood can actually be sourced for fiber. And I can spin it and I can weave with it. I can also go on a hike and look for different plant species that I can use for dyeing. And some of these dyes have really interesting properties. One, they’re natural dyes and so they’re not these kind of chemical dyes that we use in most of our garments, and where a huge amount of the pollution comes from in textile manufacturing is the dye process. So that’s kind of cool to find these alternatives. Turmeric so far is maybe the most interesting and yellow stainy dye that I really love.

Alright. So. I’m going to show you now a second little screen share. And this is kind of the obligatory “I am a professor and I’m working on a project and I really really really want people to use it.” And so, I’m going to show you…let’s see. Wherever it is. I’m gonna close out of that video… Oh boy. The power of technology.

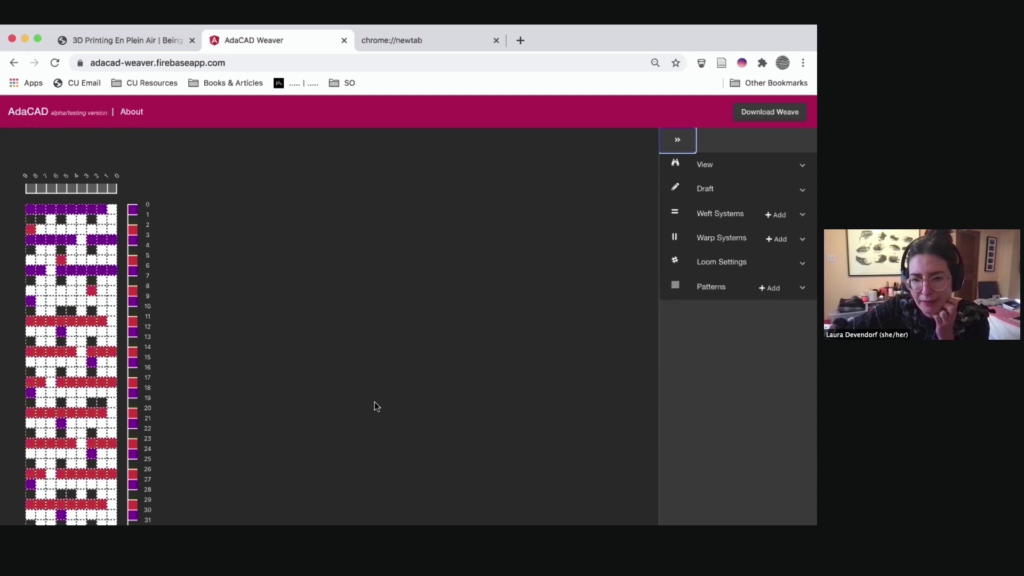

Okay. Well, I’ll give you an intro to what it is as I’m looking it up. But basically what we’ve been doing is we’ve been building open source tools for weavers. And so we actually have a deployed software. It’s open source. It’s on Github. And it’s also just free for anyone to use. And it’s called AdaCAD.

And so AdaCAD actually has some different features of notating drafts that allow you to do things like the design on different layers. It might not be super exciting if you’re not a weaver, but I would encourage people to maybe think of this as a different kind of creative coding community. So, right now I’m sort of replicating basic things weavers do, but you can imagine the sort of generative patterns that would come out. People have been really beautiful patternmaking with Glitch using different kinds of meshing algorithms to actually create woven structures that map to bodies and shapes. So, just putting this out there as something that is kind of fun to contribute to. And on this about page, you can have a link to the different Github repositories and things.

So part of the plan with AdaCAD is…maybe another ulterior motive I have as a professor is to kind of show that craftspeople are engineers. And so I think a lot of the times in my field, we see people with technical skills, traditional technical skills like computer science or electrical engineering, being comfortable sort of taking on the role of craftsperson. But at the same time we’re not very…generous with giving the term “engineer” or “technical” to people who are really from the world of craft. And I think that actually has a lot more to do with social categories and the way that we’ve assigned expertise to certain kinds of demonstratable skills. And to certain forms of knowledge that’re easily explicated. And not to people with that skill in their fingers, or that tacit knowledge. Or that maybe wanna work in a way that’s just…more attentive to the materials, more open to the materials sort of having a say in what’s created and really learning from that deep kind of material process.

So one of the things we’ve started at the university…I run a lab there called the Unstable Design Lab. And one of the things we’ve started is an experimental weaving residency. So I have a call every…let’s see, we’ll have another one I think around summer. And we have someone come in who’s a fiber artist, and we have them collaborate with an engineering team to solve a problem. And so in this residency, we just made this kind of catalog to show the different materials and structures we used.

We actually collaborated between a Finnish weaver named Sandra, who was lovely, and some aerospace engineers to create these headbands that have dry electrode structures on them that can sense muscle activity in the forehead. So this is the idea that if your astronaut is freaking out, it might be useful to know that, and that we could do that through some kind of unobtrusive sensing. So that’s been really fun. And for those of you interested, I’d encourage you to check it out on our web site, which is…I’ve written it down for you… Nope, I wrote it down on a different paper. It’s unstable.design. Here it is.

Okay! So as I close, I wanna show you maybe some of the things I do with weaving. And this kind of brings it full-scale back around to some of the things I talked about with childhood and being a mother.

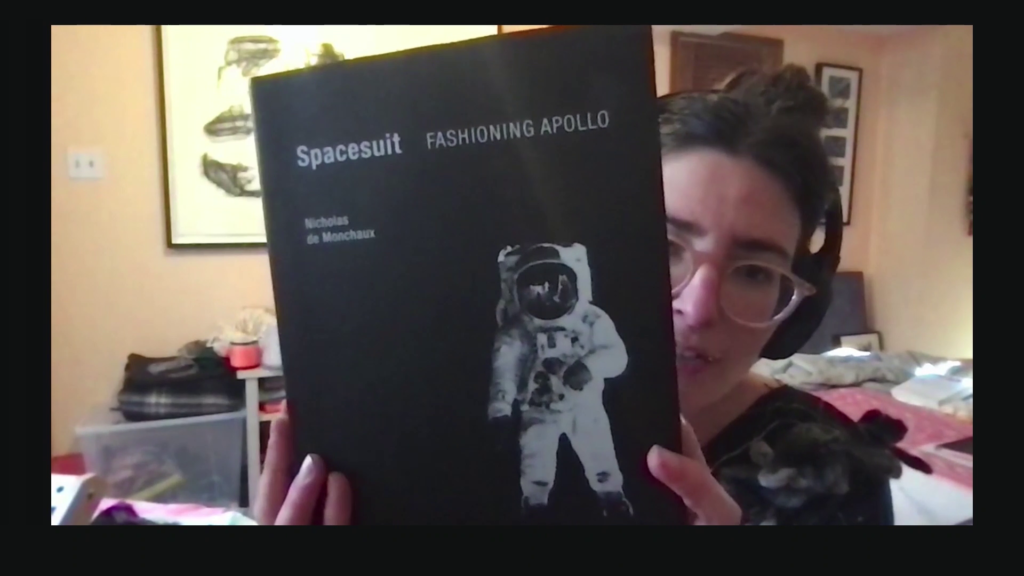

So I was really inspired by this book called Spacesuit by Nicholas de Monchaux. And this book talks about the spacesuit as body architecture. And as something that helps your body adapt to harsh environments or makes your body able to be…to inhabit spaces that it may not be meant for. And in this act of inhabiting…I’m trying to find a good picture…you actually get to see some of the forces it’s protecting you against.

So, I was just kind of interested in what would this look like if we didn’t create these kind of inhabiting suits for astronauts but for mothers. And really thinking just about my own experience as a mother.

So the first one I created in this series is called the Nipple Poncho, or the Exoskeleton for Sucking. And this makes my body more pleasurable to my children while also protecting me from being sucked on all the time, which is a very real threat as a mother. Threat. I don’t know, what am I saying?

The second is the Exoskeleton for Sedimentation. So this actually has these integrated force-sensing structures. So it actually senses the force of your children on your body over time. And I liked thinking about that in terms of erosion, or the way your body and other bodies form against each other.

Another one in this collection is the Exoskeleton for Screaming. So, in this exoskeleton I go in and I record the sounds of motors. So I walk around, and I have a little interface on here where I can record sound on this little teensy audio chip.

So I record the sounds of motors in binaural. And then I have a breath sensor here. So when I inhale and I reach the top of my inhale, the motor sounds start playing and I scream with them. And if you’ve ever screamed with a motor, it is very satisfying. And also frightening to the people who love you.

And so the last thing is this garment I’m wearing now. So this is actually one whole fabric piece that I wove. It’s about three meters long and I drape it around and wrap it around me. It is one giant PCB. And each one of these sections is a force sensor. And a color change region.

So the idea here is I’m gonna wear this for at least a week. And I’m gonna track where my body encounters force over that week. And then I’m gonna take this garment off, ship it to Hong Kong. It’s gonna be in a gallery. And those kind of interactions are gonna play back on the color change throughout the fabric. In the same way they’re also gonna generate heat. And so there’s kinda this interesting thing about my body heat being transported through space and time.

And I’m trying to find…it’s kind of an interesting wrapping structure. But here’s kind of my main control electronics. And I wove this entirely on a loom. So when Kelly Heaton last night was talking about big PCBs, I could sort of sympathize. And I might suggest weaving. So this only took me about a hundred hours to weave. And now I get to wear it around.

But with that, I am done showing you my show and tell. And yeah, just wanted to tell you a little bit about my practice and life. So thank you.

Golan Levin: Laura, thank you so much for sharing your home and your creative practice with us. That was great. I have a question from the audience, which is someone writes, “I’d love to hear about how you ended up working at this intersection. What was your path to this work, your influences?” What were you doing as a high school student and how did you end up here, at this combination of different types of technology and craft and you know, very old languages and very new ones.

Laura Devendorf: Yeah. Um…I mean growing up I was really interested in patterns and math and design. I had a thriving catalog of leotards that I made. [laughs] I was into gymnastics and so as a little kid I would just design like thousands of leotards.

I went to college for mechanical engineering, and I dropped out in the first semester. I just was having some issues I think emotionally with leaving home and I was so tired of the kind of curriculum where everything was right or wrong. And for the first time in my life I had taken an art class. And I really fell in love with the idea that the world had meaning. And I learned about semiotics. And I just was totally enraptured with this whole idea of things being more…gray.

And so, I basically finished an art degree and I worked at a clothing company as a graphic designer. And they were like a small, sustainable and organic clothing company. And then one day they needed to start a web store and I had taught myself how to do Excel macros… [laughs] And so, started building lots of macros, and then I started writing HTML, and then I started writing PHP. And then I started taking night classes at a community college in computer science.

And then I went back and did a second bachelor’s when I was about 27. And so I was the oldest female undergraduate computer science student. And I just realized I loved being in school. And so…I don’t know, it’s always crossed between the beauty in math and pattern, and the kind of beauty in humans and what we do and how we don’t make sense. I’m always trying to balance those.