Golan Levin: Hello, everyone. And welcome back to Art && Code: Homemade, digital tools and crafty approaches. I’m thrilled to welcome you now to the session with Irene Alvarado, who is a designer and developer at Google Creative Lab, where she explores how emerging technologies will shape new creative tools. She’s also a lecturer at NYU’s Interactive Telecommunications Program. Irene Alvarado.

Irene Alvarado: Hi, everyone. Very excited to be here. I’m gonna talk today about a behind-the-scenes story of a particular tool called Teachable Machine.

So as Golan said, I work at a really small team inside of Google. I mean, we’re less than 100 people, which is small for Google size. And some of us in the Lab, the work that we do includes creating what we call experiments to showcase and make more accessible some of the machine learning research that’s going on at Google. And a lot of this work shows up in a site called Experiments with Google. And time and time again we’re sort of blown by what happens when you lower the barrier for experimentation and access to information and tools. And so today I want to tell you about one particular project, and especially the approach that we took to creating it. So why am I speaking at a homemade event when I work at a huge corporation? I think you’ll see that my team tends to operate in a way that’s pretty scrappy, experimental, collaborative. And this particular project happens to be a tool that other people have used to create a lot of homemade projects.

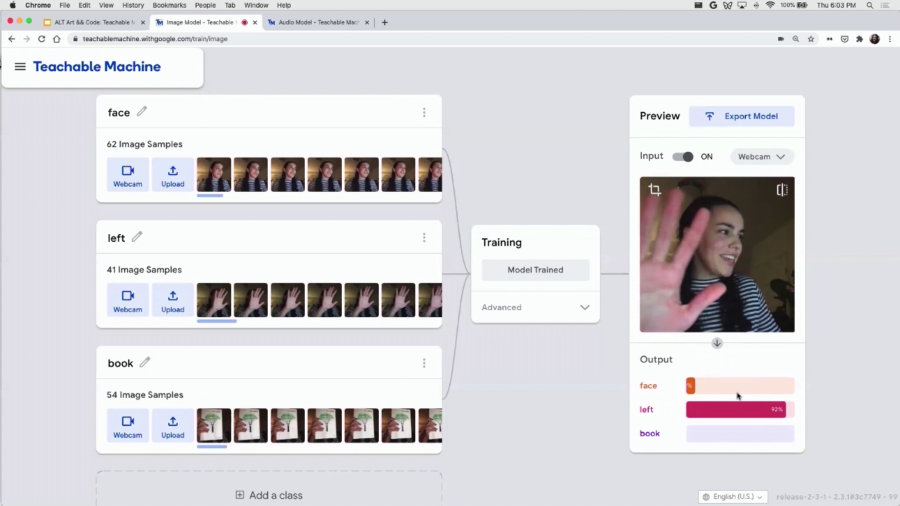

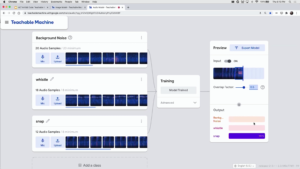

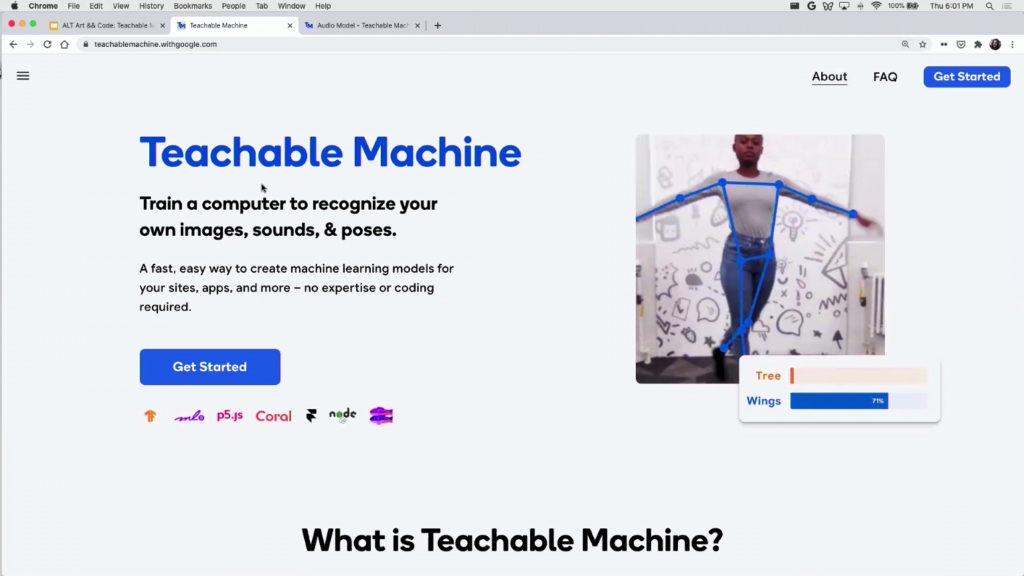

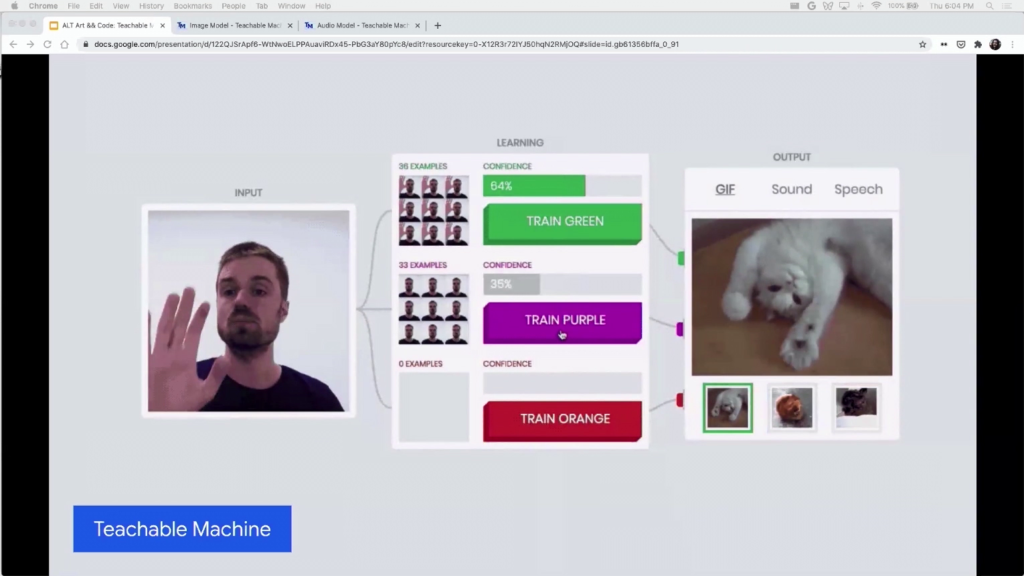

So to begin with, let me just talk about what it is. It’s a no-code tool to create machine learning models. So you know, that’s a mouthful. So I think I’m just gonna give you a demo.

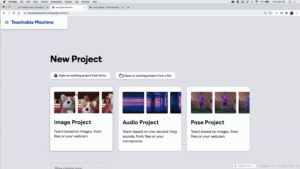

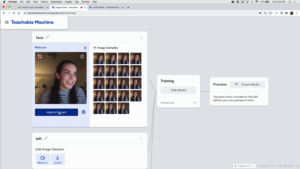

So, this is sort of the home page for the tool. It’s called Teachable Machine. And I can create different types of what we call “models” in machine learning. It’s basically a type of program. The computer has learned to do something. And there’s different types. I can choose to create an image, an audio, a pose one… I’m just gonna go for image, it’s the easiest one. And I’m just gonna give you a demo so you see how it works.

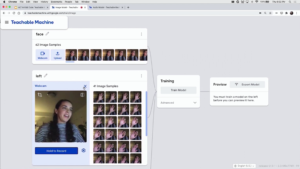

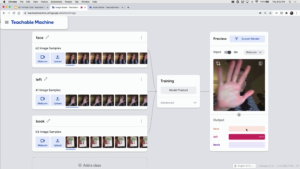

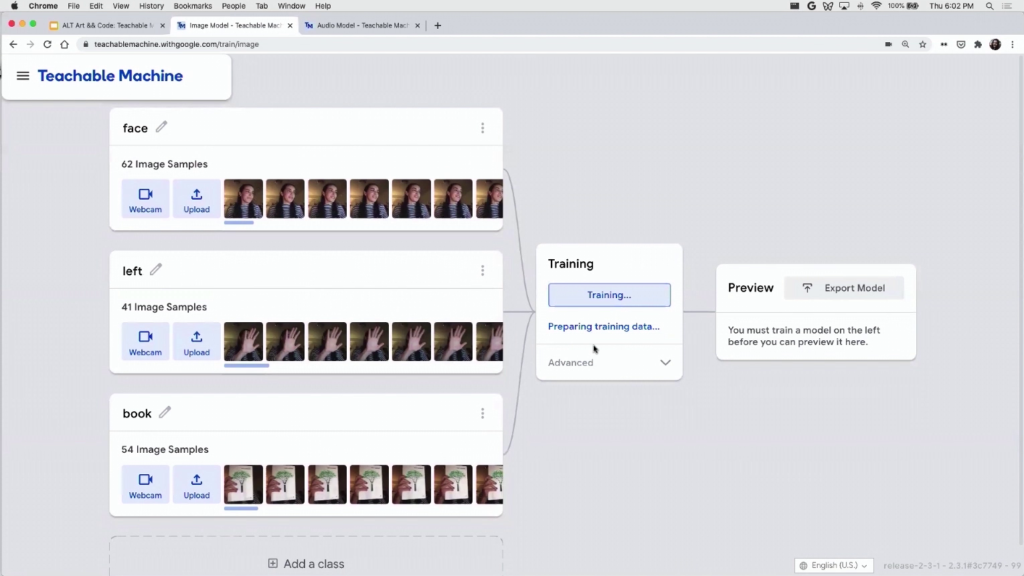

I have this section here where I can create some categories. So I’m going to create three categories. I could call this “face” or something like that. And I’m gonna give the computer some examples of my face. So I’m going to do something like this, give the computer some examples of my face.

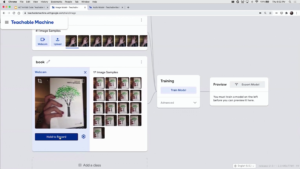

Then I’m gonna give the computer some examples of my left hand. And then I’ll give the computer some examples of a book. It happens to be a book that I like.

And then I’m gonna go to this middle section to sort of train a model. And right now it’s taking a while because all this is happening in my browser. so, the tool is very very private. All of the data is staying in my browser through a library called TensorFlow.js. So one of the main points here was to showcase that you can create these models in a really private way.

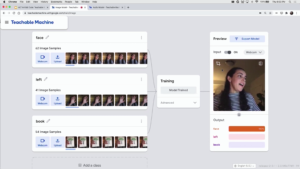

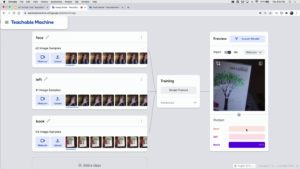

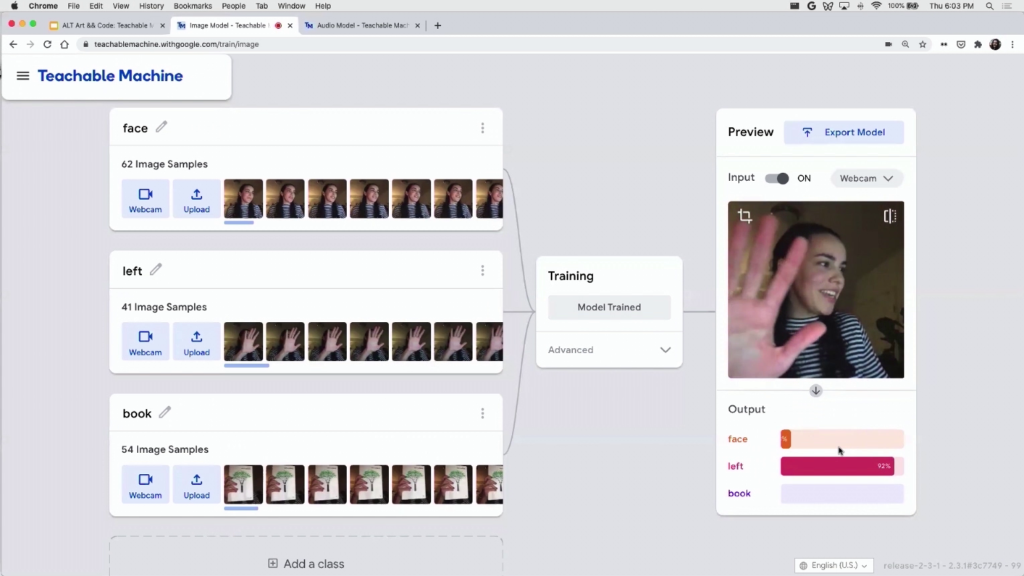

And so now the model’s trained. It’s pretty fast. And now I can try it out. I can see that it can detect my face. Let’s see, it can detect the book. And it can detect my hand.

And some interesting stuff happens. When I’m half in/half out, you see that the model’s trying to figure out okay, is it my face, is it my left hand… You can sort of learn things about these models like the fact that they’re probabilistic.

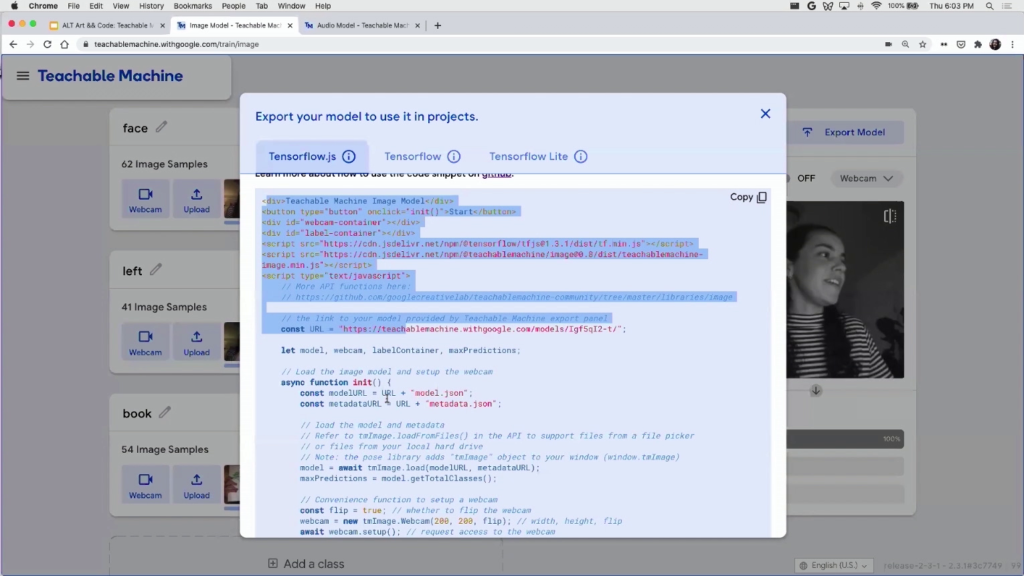

And you know, so far maybe not so special. I think what really unlocked the tool for a lot of people is that you can export your model. So I can upload this to the Web, and then if you know how to code you can sort of take this code and then essentially take the model outside of our tool and put it anywhere you want. And then you can build whatever you want with it, a game, another app, whatever you want.

We also have sort of other conversions, right. So you can create a model and not just have it on the Web. You can put it on mobile. You can put it in Unity, in Processing, in other formats and other types of platforms.

And just a little note here, of course this is not just myself. I worked on this project with a lot of very talented colleagues of mine. Some of them are here. And I’m gonna showcase a lot of work from other people in this talk so as much as possible I’m going to give credit to them. And then at the end I’ll show a little document with all the links, in case you don’t capture them.

So, I want to emphasize that a lot of our projects have really humble origins. You know, it’s just one person prototyping or sort of hacking away at an idea, even though it might seem like we’re a really big company or a really big team.

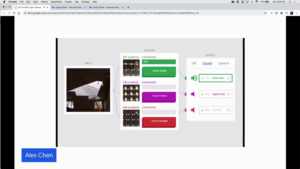

And just to show you how that’s true, you know, origin of this project was actually a really small experiment that looked like this. The interface sort of looks the same, but it was really simplified. Like you had this sort of three-panel view, and you couldn’t really add too much data. It was a really really simple project. But moreso than that, even though it was technically very sophisticated I think our ideas at the time were very…we were kind of exploring really fun use cases. And just to show you how much that’s true, I’ll show you a project that one of the originators of this idea, Alex Chen, tried out with his kid.

So you can see he’s basically creating these paper mâché figurines with his kid, and so he’s training a model that then triggers a bunch of sounds. So it was really kind of fun at the time just trying a lot of different things out.

And then we started hearing from a lot of teachers all over the world who are using this as a tool to talk about machine learning in the classroom, or talk about sort of the basics of data to kids. And then we finally heard even from some folks in policy. So Hal Abelson is a CS professor at MIT, and he was using the tool to conduct sort of hands-on workshops with policymakers.

So, we had a hunch that maybe this silly experiment could become something more but really didn’t know how to transform this into an actual tool. We also don’t know necessarily what the best use cases would be. This is where the project took a really really interesting turn, because essentially we met the perfect collaborator to push us into making it a tool.

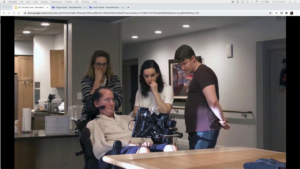

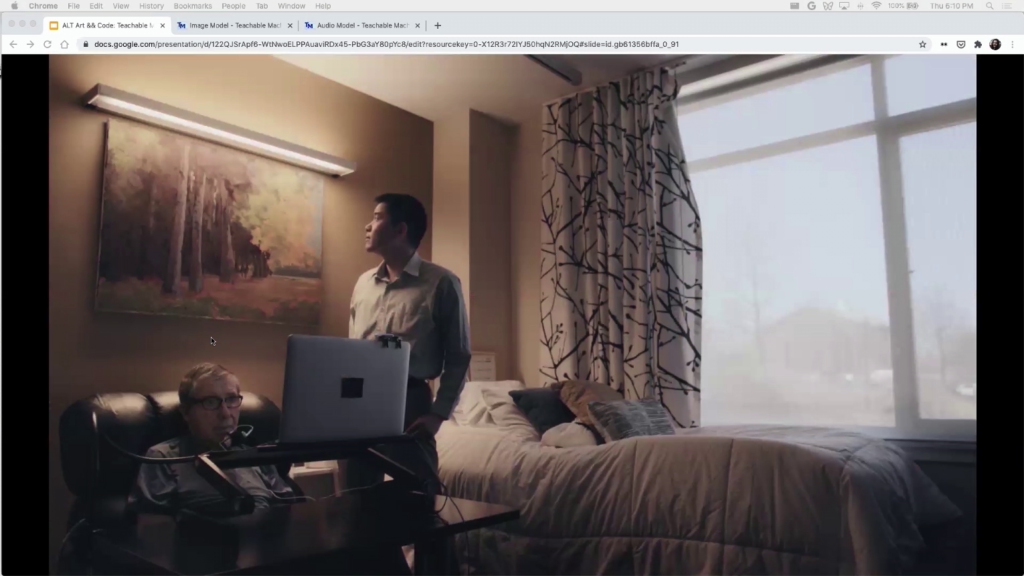

And that person, his name is Steve Saling. He was introduced to us by another team at Google who had been working with him. And Steve is this amazing person. He used to be a landscape architect and he got ALS, which is Lou Gehrig’s disease. And he sort of set out to completely reimagine how people with this condition get care and he created this space that…everything is API-fied. So he’s able to order the elevator with his computer, or turn on the TV with his computer. It’s really amazing. And so he actually found the original Teachable Machine, and someone else sort of was using it with him. And we basically got introduced to him and the question was well you know, can we figure out if this could be useful to him and in what way. And how do we just get to know Steve and what he might want.

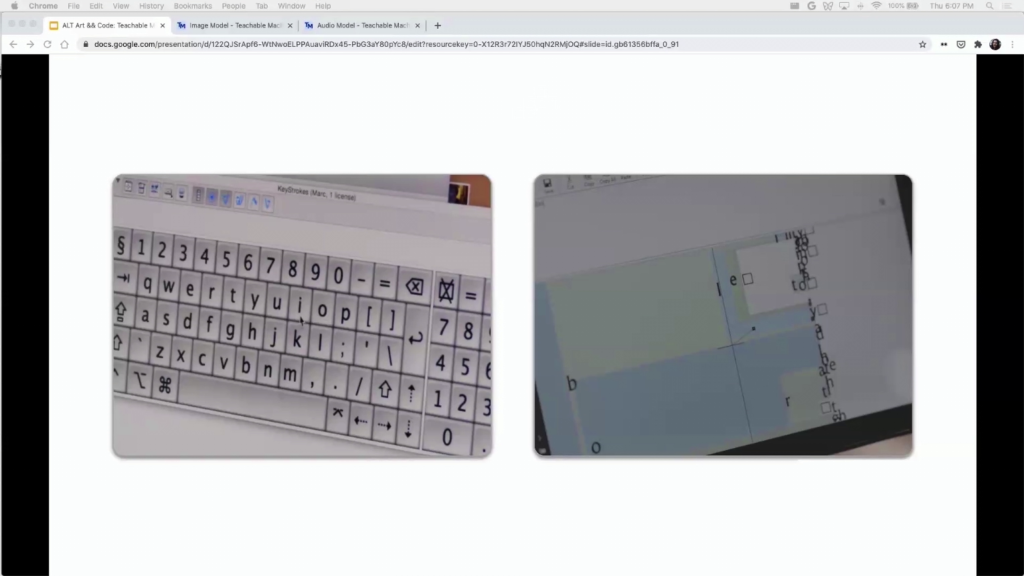

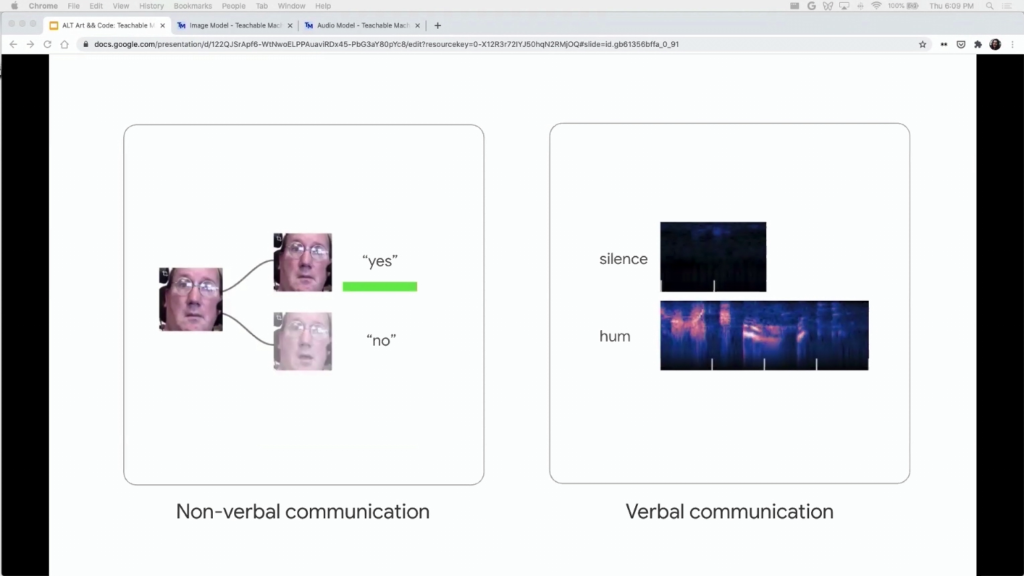

So, a little pause here to say that folks like Steve, they aren’t able to move or in Steve’s case he’s not able to communicate. So he uses something called a gaze tracker, or a head mouse. And he essentially sort of looks at a point on the screen and can sort of press “click” and type a word or a letter. So he’s able to communicate but it’s really really slow.

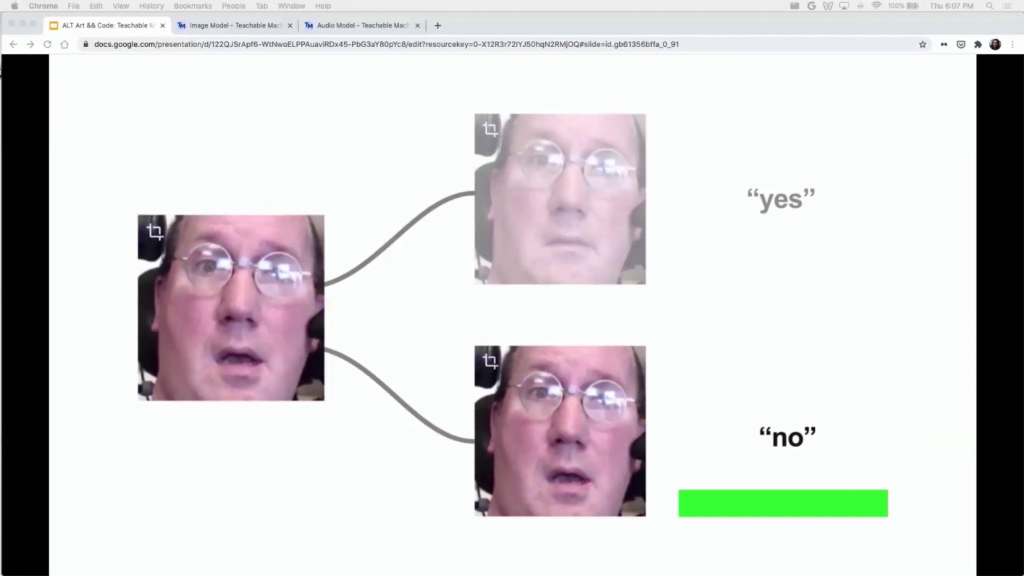

And so the thought was okay, can we use a tool like Teachable Machine to train a computer to detect some facial expressions and then trigger something. And this of course is not new. The thing that was sort of new was not for me to train a model for him, but for him to be able to load the tool on his computer and train it himself. Like sort of put that control on Steve.

And specifically, we basically went down to Boston and worked with him quite a lot. He became sort of the first big user of the tool and we made a lot of decisions by working with Steve and sort of following his advice.

And one of the things that the tool sort of allowed us to explore was this idea of immediacy. So, what were some cases were Steve wanted sort of a really quick reaction, and how could the tool help for this?

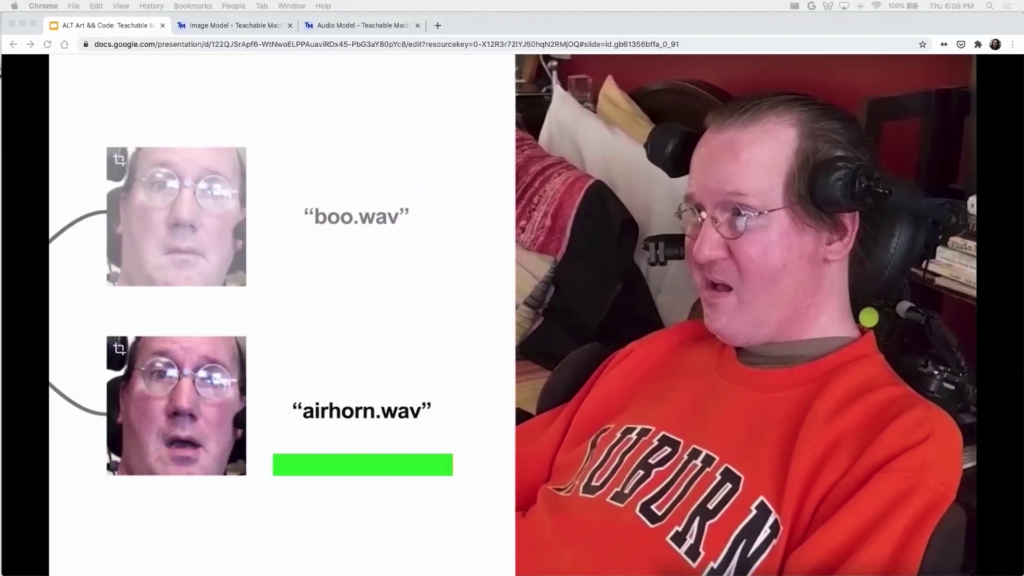

And one use case was he really wanted to watch a basketball game, and he really wanted to be able to cheer or to boo depending on what was happening in the game. And that was something that he was not able to do with his usual tools because you have to be really fast in cheering or booing when something happened. And so, he trained a simple model that basically he could sort of open his mouth and trigger an air horn. So that was one example.

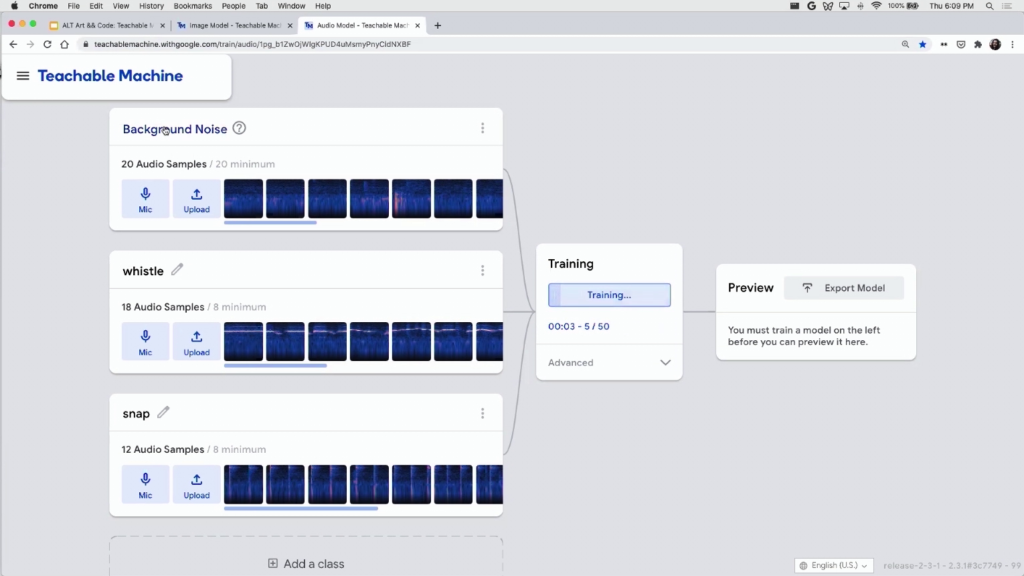

So we kind of immersed ourselves in Steve’s world, and by getting to know him we got to know that maybe other ALS users can find something like this useful. So we started exploring audio. Like, could we have another input modality to be audio to potentially help with people who sort of had limited speech? And that led us to incorporate audio into the tool. So I actually have a little example here that I also want to show, just so you guys see how this works. I’m loading up a project that I had created beforehand from Google drive.

This is some data that I had collected beforehand, some audio data. So there’s three classes. There’s background noise, there’s a whistle, and there’s a snap. And let’s see if it works.

So you can see the whistle works. You can see the snap works. So same thing here. I can kind of export the model to other places.

But the interesting thing here is that the audio model itself actually came from this engineer named Shanqing Cai, and he created that audio model for people like Marc Abraham who also have ALS through exploring with him the same idea, like how can I create models for people like that so that they can trigger things on the computer. So the technology itself also came from this exploration of working with users who have ALS.

And you can’t see what’s happening here but essentially Dr. Abraham has sort of emitted a puff of air, and with that puff of air he’s been able to turn on the light.

So we decided that okay, this could be useful to other people who have ALS, and we decided to essentially open up a beta program for other people to tell us if they had other similar uses. And trying to think about maybe other analogous communities that could find some interest in Teachable Machine.

And that’s how we met the amazing Matt Santamaria and his mom Cathy. And Matt had come to us and told us that he was playing with the tool and she wanted to try to use it for his mom. So he actually created a little photo album that would sort of change photos for his mom and he could load them remotely. But his mom, because she didn’t have really too many motor skills because she had a stroke, she wasn’t able to control the photo album.

So we actually worked with Matt, and you can’t see it here because it’s just an image but we actually worked with Matt to create a little prototype of his mom being able to say “previous” or “next,” and then training an audio model that then was able to change the picture that was being shown on the slideshow. And that was just sort of a one-day hack exploration that we did with Matt.

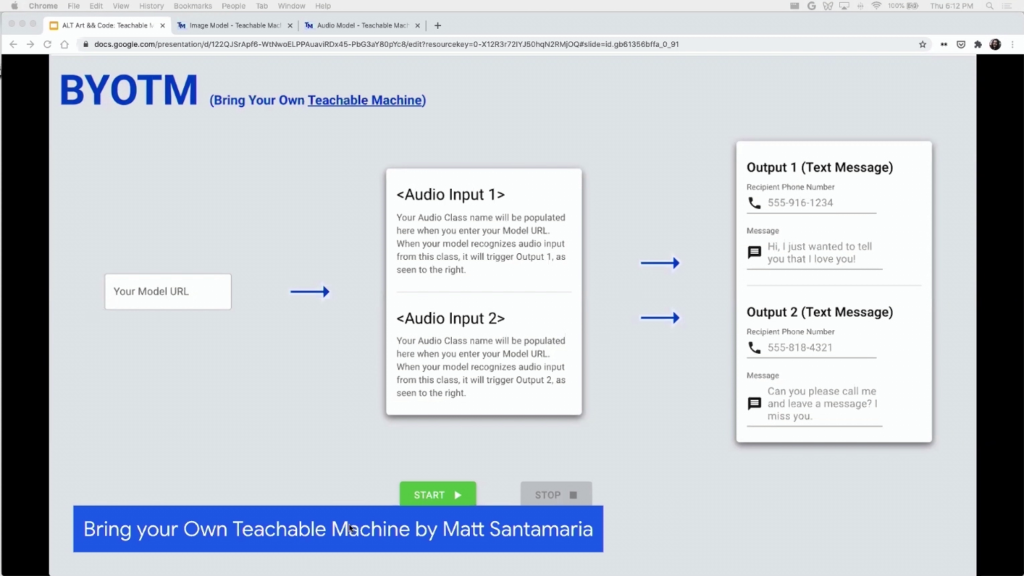

And then ultimately he sort of kept exploring potential uses of Teachable Machine with his mom, and he created this tool called Bring Your Own Teachable Machine, which he open sourced and has shared online. And what it allows you to do is to put any type of audio model and then link that to basically a trigger that sends a text to any phone number. So, pretty cool to see what he did here.

And then finally, just seeing that the tool sort of ended up being useful in a lot of analogous communities, once we launched it publicly we saw a lot of uses outside of accessibility. So I wanted to show you a few of my favorite ones today.

This is a project by researcher Blakeley Paine. She used to study at MIT Media Lab. And she was really interested in exploring how to teach AI ethics to kids. So she open sourced this curriculum. You can find online. And it just has a bunch of exercises, really interesting exercises, that she takes kids through.

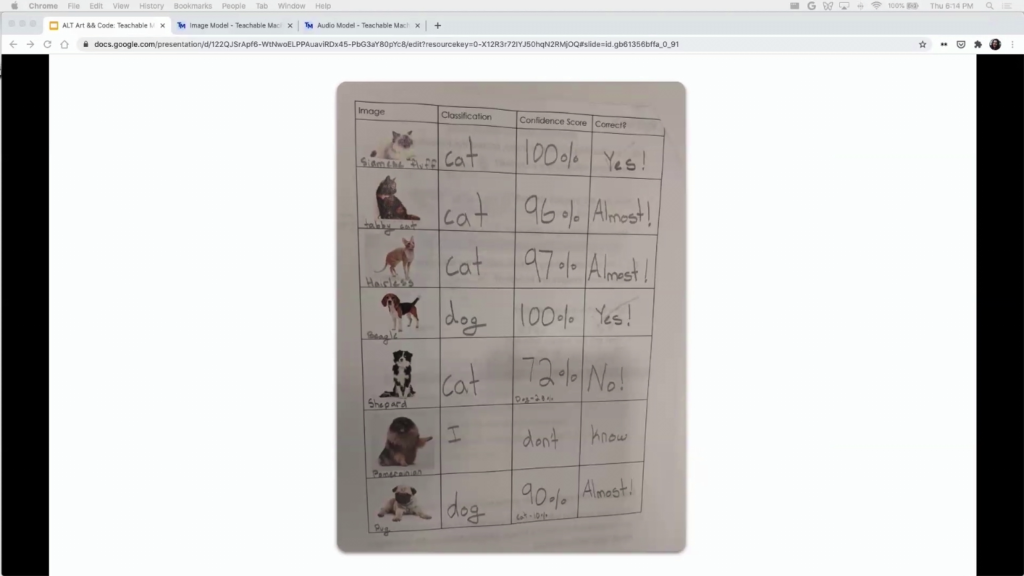

So this one for example explains to them the different parts of a machine learning pipeline. So in this case collecting data, training your model, and then running the model. She sort of gives them different data sets. So you can see here in the picture—it’s little blurry but you can see the kids got forty-two samples of cats, and then seven samples of dogs. And so the idea’s for them to train a model and then see okay, maybe the model’s working really well in some cases, maybe it’s working really poorly in some cases. Why is that? And have a conversation with them about AI ethics and bias and sort of how training a model is related to the type of data that you have.

Here’s another example of her workshop. She sort of asks kids to label their confidence scores. And you’d be surprised. We were invited to join one of the workshops and these kids sort of establish a pretty good kind of insight into the connection between how the model performs and the type of data that it was given.

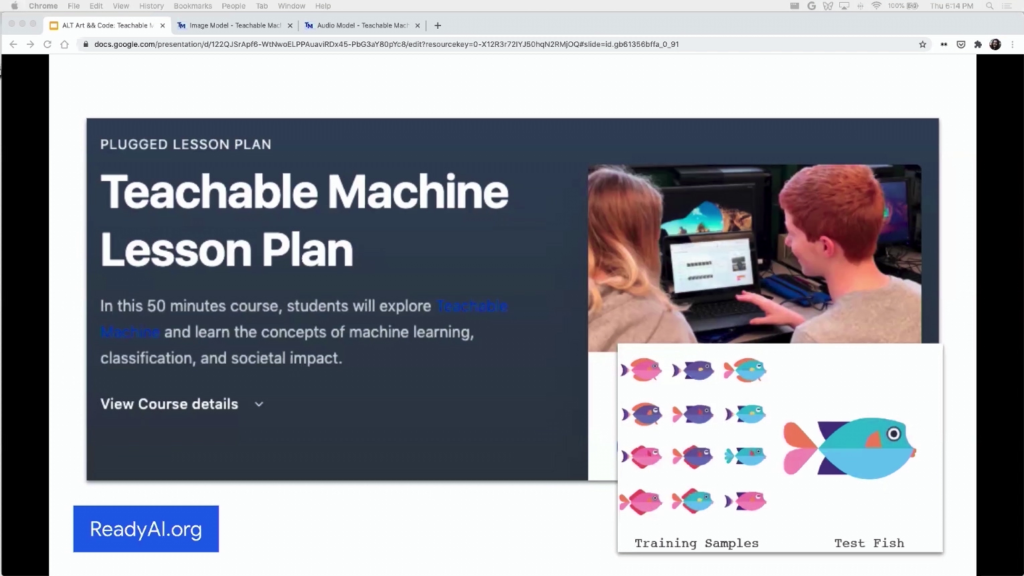

It’s not just Blakeley. There’s other organizations that have created lesson plans. This one is called ReadyAI.org. And again, they kind of use these simple training samples. In a lot of school you can’t use your webcam. So a lot of them sort of have to upload picture files or photo files in order to use the tool. And that was a use case that we found out through education, that we have to sort of enable not having a webcam.

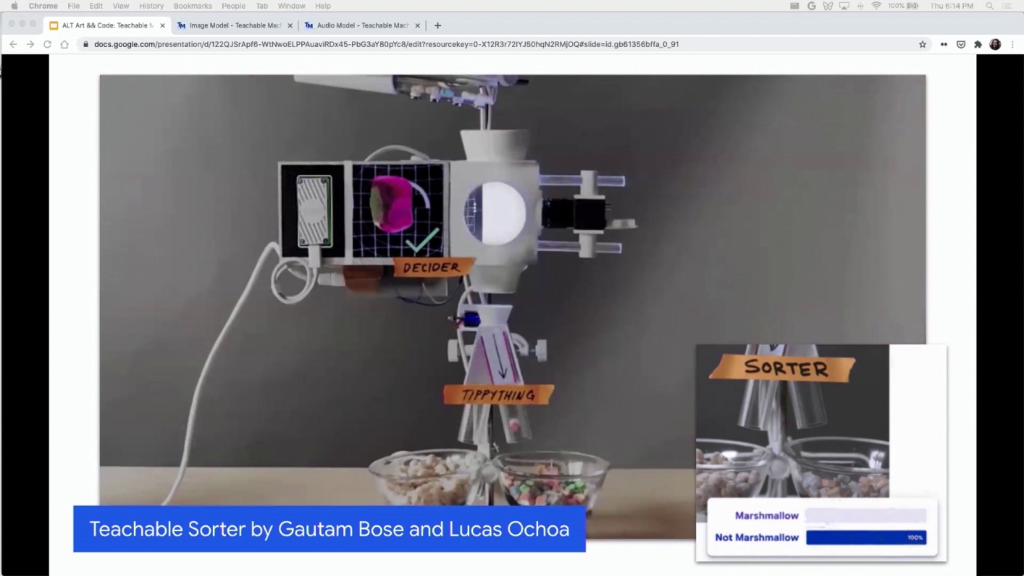

Sorting Marshmallows with AI: Using Coral + Teachable Machine [an excerpt of this video plays muted as Alvarado describes the project]

And then more in the realm of hardware, there’s a project called Teachable Sorter, created by these amazing designer/technologists Gautam Bose and Lucas Ochoa. And what it is is this very sort of powerful sorter. So, it uses this accelerated hardware board; it’s kind of like a Raspberry Pi. And they essentially train a model in the browser and then they export it to this hardware. And they both were super super helpful in sort of creating that conversion between web and this little hardware device.

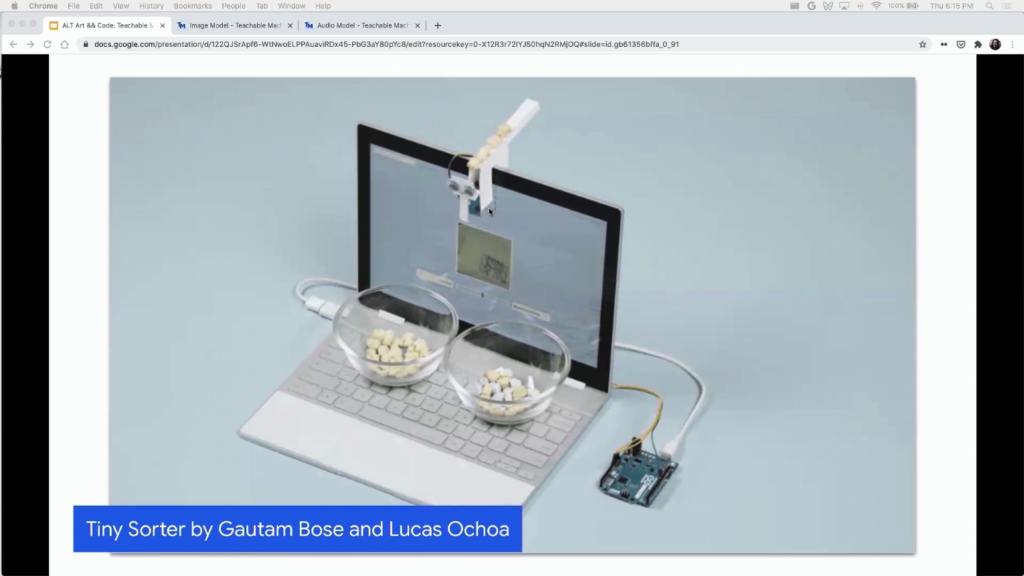

Now, this is a very complex project so they made a simple version that’s open source and you run instructions online. And it’s a Tiny Sorter. So a sorter that you can put on your webcam. And so again, you can train a model with Teachable Machine in the browser, and then export it to this little Arduino and then sort of attach this to your webcam and sort things.

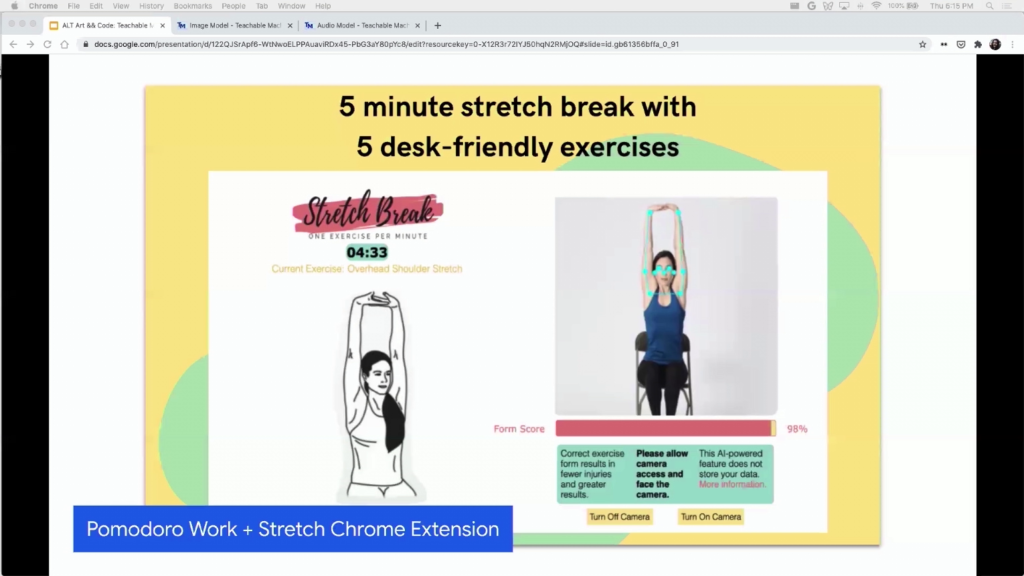

In a different vein, there’s this project called Pomodoro Work + Stretch Chrome extension. And what it is is it’s a Chrome extension that reminds you to stretch. And the way it works is this person trained a pose model that basically detects when people are stretching, right.

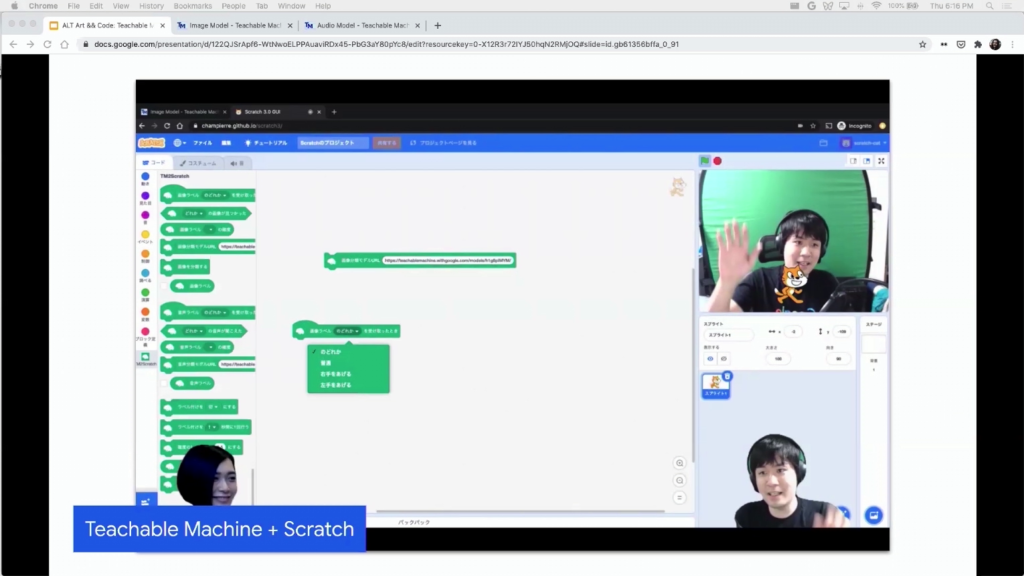

There’s a team in Japan that integrated Teachable Machine with Scratch. Scratch is a tool for kids to learn how to code. It’s a tool and a language environment for children to learn how to code. And unfortunately a lot of the tutorials are in Japanese, but the app itself sort of works for everybody. So you can take any model and run it there.

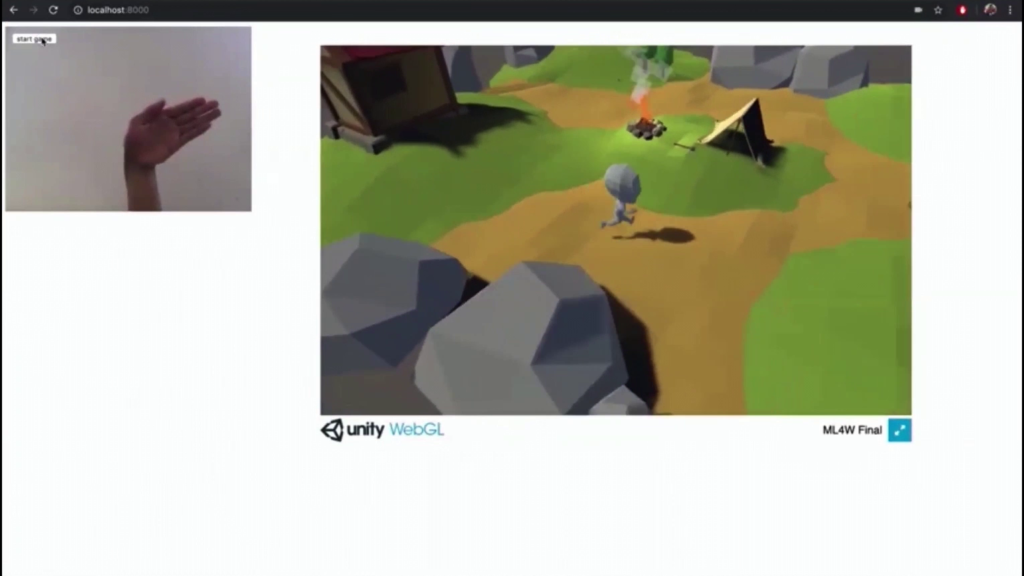

And then a lot of other just really creative projects. Like this one is called Move the Dude. So it’s a Unity game that you control with your hand. And your hand essentially is what’s moving the little character around. So again, because these models work on the Web you can kind of make a Unity WebGL game and export it.

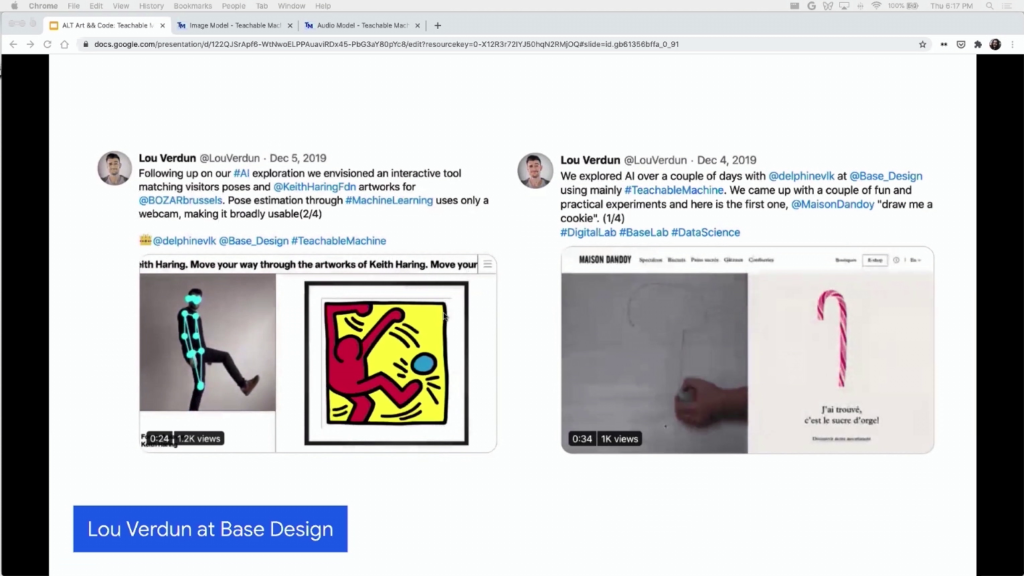

And then just one last example. A lot of designers and tinkerers started using the tool to just play around with funky design. So Lou Verdun created these little sort of explorations. In this one he’s doing different poses and matching those poses to a Keith Haring painting. And then in this one it’s sort of like a cookie store? And then you can draw a cookie and get the closest-looking cookie.

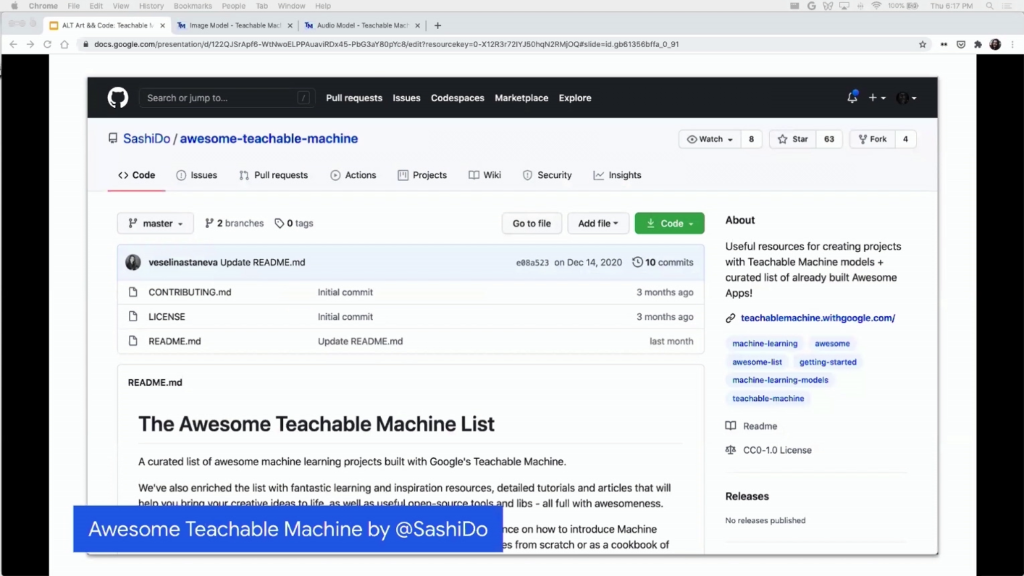

And then this Github user SashiDo created a really awesome list of a ton of very inspiring Teachable Machine projects, in case you want to see more of them.

So, just to sort of go back to the process of how we made this tool. We took a bit of time to think about this way of working and informally started calling it “Start with One” amongst ourselves, amongst my colleagues. And it’s not a new idea, you know. This is inclusive design. I’m not inventing anything new. Just the words Start with One sort of was a way to remind ourselves that…you know, of the technical nature of it. Like, you can just choose one community, one person, and sort of start there. And we’re really just trying to celebrate this way of working, this ethos. Start with one was just an easy way to remember that.

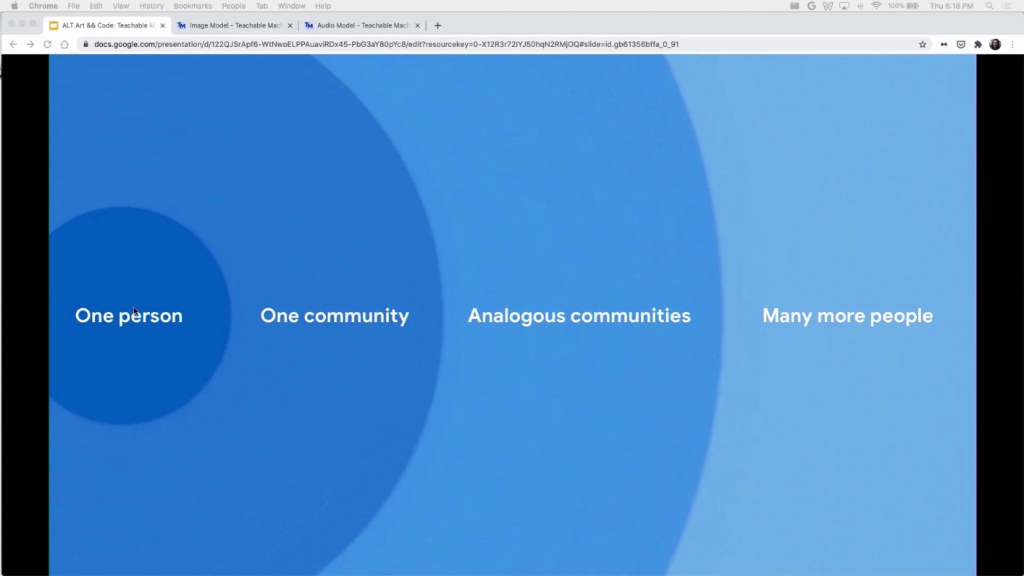

So, just coming back to this chart for a second. This idea of like a tool that we created for one person ended up being useful for a lot more people. But I want to clarify that the goal is not necessarily to get to the right of this chart. A lot of the projects that we make, they just end up being useful for one person, or for one community. And that’s totally okay. And it’s not necessarily the traditional way of working at Google, but it’s okay for my team.

And you know, this idea of sort of starting with maybe the impact or the collaboration first rather than the scale, it doesn’t mean it’s the only way of working, it doesn’t mean it’s the best way of working. It’s just a way of working that has worked really well for my very small team.

So there are a lot of other projects this sort of fit into this bill, and if you’re curious about them you can see some of them in this page, g.co/StartWithOne. It’s also page where you can submit projects, right, so if any of you have a project that fits into this ethos, you’re welcome to submit there. And you know, right now that times are really hard for people, I think it’s easy to be crippled by what’s going on in the world. I’ve certainly felt that way. Maybe even a little powerless at times. And for me, when I think of Start with One, I remember that you know, even small ideas can have a big impact if you apply it in the right places. And I don’t just mean pragmatic, right. Like, human need is also about joy and curiosity and entertainment and comedy and love. So it’s not just a practical view of this.

So, just a little reminder for all of you, I suppose, to look around you, to collaborate with people who are different than you. Or even people who you know really well—your neighbors, your family. I think the idea is to offer your craft, and collaborate with a one, and solve something for them. You know, even if you’re starting small you’d be really surprised by how far it can get.

That’s it. There’s this link, tinyurl.com/teachable-machine-community I’ll paste in the Discord. And you can find all the other links in my talk through that link, in case you didn’t have time to copy it down. Thank you very much.

Golan Levin: Thank you so much, Irene.

Irene Alvarado: I’ll keep this up for a little bit just in case.

Levin: Yeah, that’s great. Thank you so much. It’s beautiful to see all these different ways in which a diverse public has found ways to use Teachable Machine in ways that are very personal and often you know, scaled to what a single person is curious about. Like you know, a father and a child, or people with different abilities who can use this in different ways to make easements for themselves. It’s really amazing.

I’ve got a couple questions coming from the chat. So, you mentioned this Start with One point of view. Is this a philosophy that’s just your sub-team within Google Creative Lab? Or does Google Creative Lab have a manifesto or set of principles that guide its work in general? And if so what sort of guides the work there, and how do you fit into that?

Alvarado: Yeah, great question. No, I wouldn’t say it’s like a general manifesto, or even of the lab itself. I would say it’s a way of thinking within my sub-team of the lab.

And again, I do want to say it’s not like I’m talking about anything new. Like inclusive design and codesign…been talking about this for ages. It’s really just like a short-word, keyword, for us to refer to these types of projects. But I would say the Creative Lab does pride itself in basically embarking on close collaborations. So we tend to see that projects where we collaborate very closely—like not making for people but making with people—end up being better. So, not all projects can be done in that way necessarily, but I would say a good amount are.

Levin: So I know that there’s a sort of coronavirus-themed project that uses the Teachable Machine, by I think it’s Isaac [Blankensmith], which is the Anti-Face-Touching Machine, where he makes a machine that whenever he touches his face it says, “No” in a computer-synthezized voice. It’s super homemade and it sort of trains him to stop touching his face.

But I’m curious, how has the pandemic changed or impacted the work that your team is doing, or that people that who are working with Teachable Machine are doing, or that the Creative Lab is doing. How have things shifted in light of this big shift around the world?

Alvarado: Yeah. I mean, that’s a good question. I don’t know if I have an extremely unique answer to that except to say that we’ve been impacted like anybody else. I mean, luckily am in an industry where I can work from home, so I feel incredibly lucky and privileged to be able to be at home, safe, and not be a frontline worker.

It’s changed the fact that certainly collaborations are harder to do. Like you saw in the pictures with Steve, we like to go to where people are and sit next to someone and actually talk to them and not be on our computers. And that has certainly gotten harder. But we’re trying to make do with things like Zoom, just like everybody else.

I’d say the hardest thing is not collaborating with people in person. It just takes like a shift? because there’s so much Zoom fatigue. And you don’t get to know people outside of your colleagues. Like when I’m trying to know a collaborator or someone outside of Google, like anybody else you benefit from going to dinner or grabbing coffee or just like be a normal person with them, having a laugh. And that doesn’t really exist anymore. Like Steve actually, the person that I was talking about who has ALS, he’s so funny. Like he says so many jokes. He’s so restricted with the words that he can say because it takes him a long time to type every sentence, you know, it takes two minutes to type a sentence. But he’s so funny. He has such a great personality and humor. And I think that would be very hard to come off through Zoom. Starting with the fact that it’s very hard for him to use Zoom because someone else has to trigger it for him. So certainly that type of collaboration would’ve been very hard to do this year.

Levin: Thank you so much for sharing your work and this amazing creative tool. I like to think that there are several different gifts that each of our speakers are giving to the audience. And one of them is kind of just the gift of permission to be a hybrid, right. Like you are a designer, and a software developer, and an artist and a creator and an anthropologist and all these other kinds of—you know, things that bridge the technical and the cultural, the personal and the design-oriented, and all this together.

Another gift is just the gift of the tool that you’re able to provide to all of us. Me, and my students, and kids everywhere, and adults. Thank you so much.

Alvarado: Yeah I mean, final words is that it’s a feedback loop, right? Like I was inspired by your work, Golan. Like you give a lot of people in this community permission to be hybrids, and I didn’t know that that was possible. And then everyone making things with Teachable Machine inspires us to do other things or to take the project in another direction. So I think we have the privilege and honor of working in an era where the Internet just allows you to have this two-way communication. And I think it makes so many things better.

So thank you, Golan, and thank everyone for organizing the conference like Lea, Madeline, Claire, Bill, Linda. You guys all make hybrids around the world possible.

Levin: Thanks a lot, Irene.

In a few minutes, at 6:30, we’re going to begin a lecture presentation by Andrew Quitmeyer from the Digital Naturalism Laboratories in Panama. And so we’ll be seeing Andrew pretty soon. Thanks, everyone. See you soon.