Golan Levin: Hello. And welcome to Art && Code: Homemade. My name is Golan Levin, professor of electronic art at Carnegie Mellon University, and directory of the Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for Creative Inquiry, our laboratory for atypical, antidisciplinary, and inter-institutional research and programs at the intersection of the arts, science, technology, and culture.

I’m thrilled to welcome you today to the fifth edition of our sporadic Art && Code festival, which is concerned with democratizing the cultural and creative potentials of emerging technologies. Our festival runs now through Saturday evening, and you can find more information about our festival including a complete schedule of presentations at artandcode.com/homemade. We have also a Discord server to support community conversations. And if you are interested in participating in those chats, we ask you to please register at artandcode.com to receive the link.

These are dark and isolating times. It’s January in the Northern Hemisphere, and the days are short and cold. Civic life has fractured, authoritarianism is on the rise, and it feels like the twilight of American and representative democracy. We’ve spent more than 300 days indoors, with no clear end in sight. And quarantined due to COVID-19, we long to see our family, friends, collaborators, and peers. The joke goes that we are not working from home but rather living at work. Yet as artists and designers, many of us have been separated from the tools of our trade—our studios, makerspaces, and laboratories are closed, so that we are limited to what we can make in our own homes. And more than ever, we feel alienated by the mass-produced nature of our material culture. How can we stay vitally creative and connected at this moment?

In this context, we are thrilled to present Art && Code: Homemade, a free online festival featuring inspirational talks by creators we admire who work with digital tools and crafty approaches to make things that preserve the magic of something homemade. Our festival features a wide range of practitioners who are exploring poignant and personal new approaches to combining everyday materials, craft languages, and cutting-edge computational techniques, gift cultures, cardboard and clay, and pocket supercomputing, towards the neo-homemade. Our festival offers an extended conversation between creators working with digital tools, crafty materials, and tight constraints to make things that don’t scale. Homemade is resourceful, personal, and community-driven. It’s accessible and grassroots. Homemade means made with care.

Art && Code: Homemade, our festival, has been made possible by an award from the Media Arts program of the National Endowment for the Arts, by the Sylvia and David Steiner Speaker Series at Carnegie Mellon University, and by support from generous donations to the Director’s Fund at the Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for Creative Inquiry.

Finally, the Art && Code conference series is a project of Carnegie Mellon University. Located in the city of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, we acknowledge that we operate on land that has been continuously inhabited for over 16,000 years, the traditional land of the Monongahela and Haudenosaunee peoples past and present, and we honor with gratitude the land itself and the people who have stewarded it throughout the generations. This calls us to commit to continuing to learn how to be better stewards of the land we inhabit as well.

Our first speaker tonight is Claire Hentschker, a Brooklyn-based artist and designer exploring media arts and crafts. Claire is in many ways the origination point for the Art && Code: Homemade festival, which arose out of her graduate work here at Carnegie Mellon. And in collaboration with Lea Albaugh and Madeline Gannon, Claire is also a member of the three-person curatorial advising team for Art && Code: Homemade.

Please welcome Claire Hentschker.

Claire Hentschker: Hi, everybody. Thank you so much for having me. And I’m gonna share my screen now.

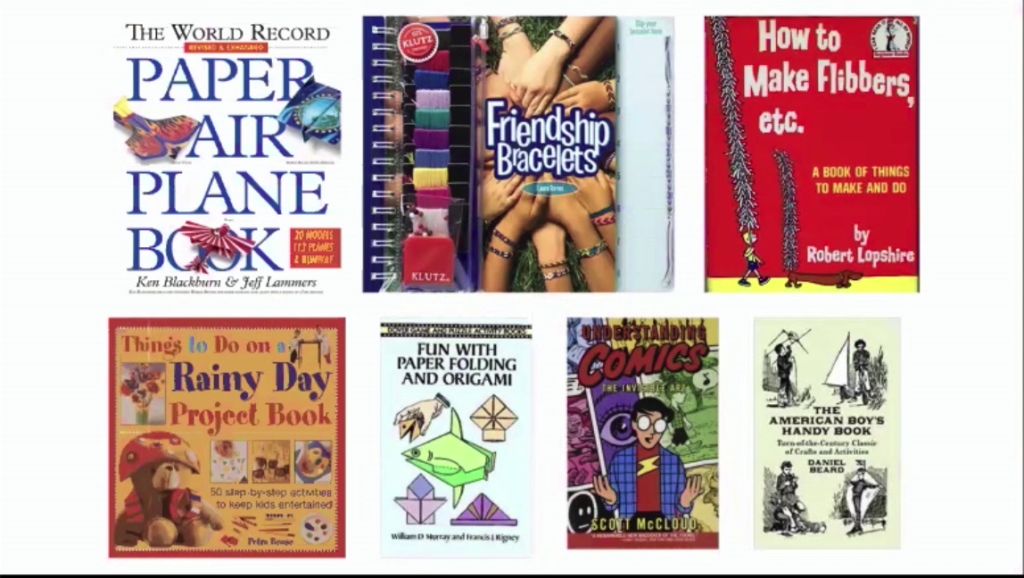

So, as Golan mentioned I’ve been increasingly interested in this idea of media arts and crafts, and thinking about…honestly what that means. And so I actually selfishly have a question for everybody. And if you’re in the Discord server, feel free to answer this here, or like send me an email. Or something to think about. And it’s like a question and also a hypothesis. I’ll tell you the hypothesis after. But, the question is, did you have a book when you were younger that was somehow like a DIY, or arts and crafts, or some sort of instructional making guide for kids that had a lasting impact on you?

And I ask this because it was a point of my research a couple years ago and it started to get really interesting when everyone who I admired in the field of media and tech and art started to like immediately have an answer which was like yes, of course. It was the how to make paper airplanes book. Or obviously it was the origami book. Or one of my favorites ones was how to make a flipper? I hadn’t heard of that but it was an excellent introduction that I believe it came through Everest Pipkin.

So, tell me if you have one of these, because I’ve been collecting them for a while because I think the tone of these books is what’s really drawn me to the term “arts and crafts” and homemade as a really positive, love-filled, process-based, highly respectable genre of making. And I’m always interested in hearing more about what other people’s connections are to this idea.

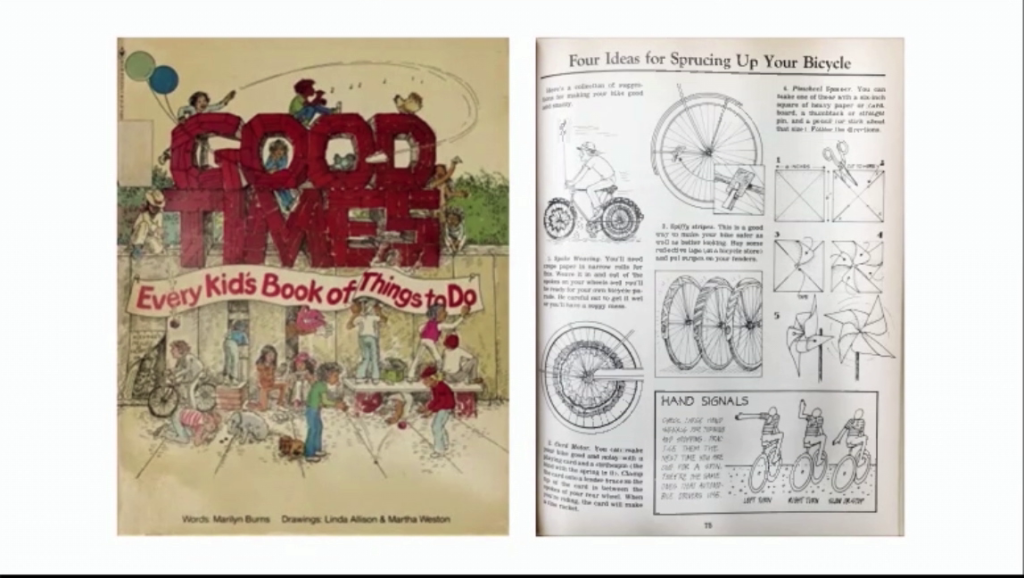

Golan actually introduced me to this book which is called Good Times. And I think it’s so lovely because here is a page from the book, and it’s four ideas how to spruce up your bicycle. And the whole thing is hand-done and hand-illustrated. And it’s all about essentially why you have no excuse ever to be bored. Why you can constantly throw yourself into the process of making something with your hands, at home, during a rainy day, with your friends. And the emphasis is on sort of relaying this information to you non-judgmentally and under the guise of fun, not as some sort of skill for a future job. This is sort of the craft angle that I’m interested in.

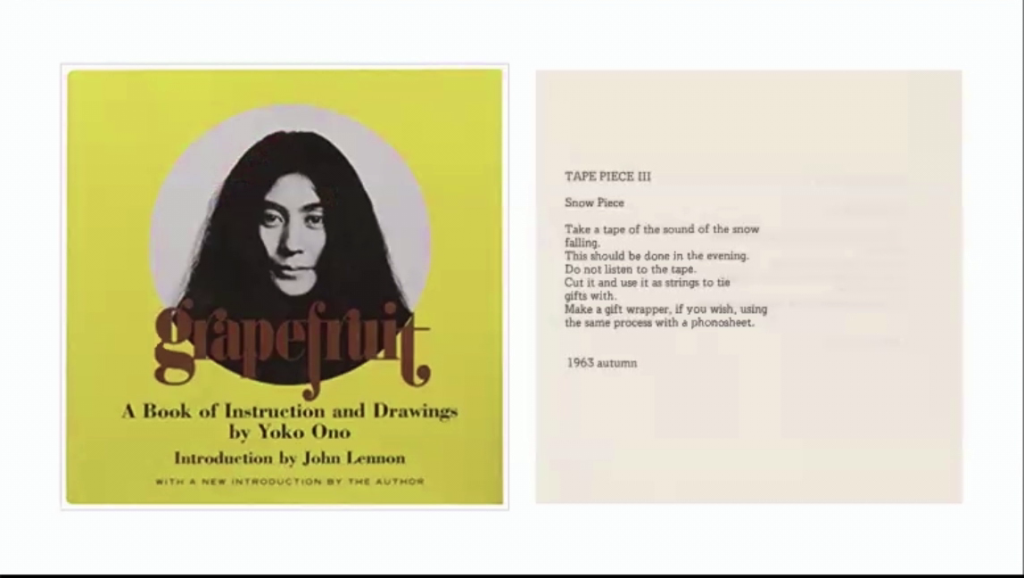

So then the next word in media arts and crafts is “art.” And there’s a totally similar style of book too that I find equally interesting. It originated maybe in the Dada movement but then was seen again in Fluxus with Yoko Ono who created this Grapefruit book, and it was a set of instructional drawings and performance pieces that were in the form of verbal instructions.

So this one is a favorite of mine. It’s called Snow Piece.

Take a tape of the sound of the snow falling.

This is should be done in the evening.

Do not listen to the tape.

Cut it and use it as strings to tie gifts with.

Make a gift wrapper, if you wish, using the same process with a phonosheet.

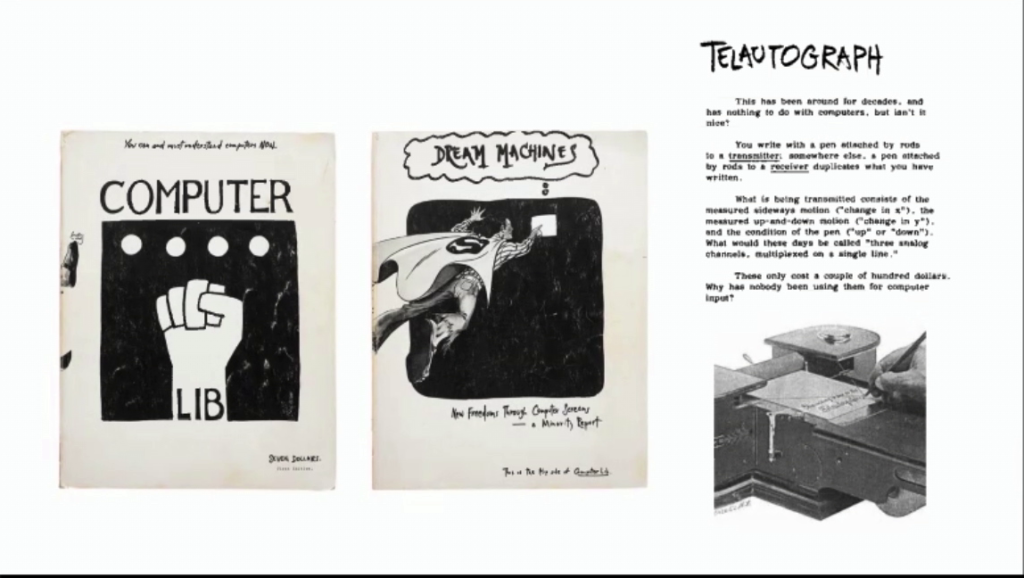

And I think the is same sort of attitude towards making and sharing the sort of instructions behind how to make something is also visible in the history of tech. And one of my favorite examples of this is Ted Nelson’s Computer Lib/Dream Machines, which is like a totally insane book that reads two different ways. Like you can read it from one side this way and then read it from this side the other way. And half of it is him sort of breaking down to a novice why a computer could be a tool that they could interact with. Then the other side is this sort of wild speculative future of his where he talks about what he thinks the future of computing as a sort of…I want to say a craft-based medium looks like. And one of my favorite examples is he calls attention to the Telau— I just realized I’ve never said this out loud until right now. The Telautograph?

But essentially it was one of the first writing tablets that used a special sort of pen to transmit handwriting over signals. And he calls this out as an interesting piece of technology, and why has no one used this in computing before? Which of course now if you look at anything from the the like fax machine to the iPad it’s of course completely used. So I just thought it was an interesting way that his sort of speculation his looking at tools and making started to dictate what actually happened in the future.

So then if you fast forward, I think there is like this unbelievably interesting thing happening all over HCI, computation, and art. And I was exposed to it through the STUDIO for Creative Inquiry, which is Golan’s lab. But this idea of sort of crafty approaches to technical problems. And I don’t know, I think because I had been thinking so much about these sorts of arts and crafts books, I think about— Every time I come across an example of these that I love, I think about it as like what it would be as a rainy day activity for the future.

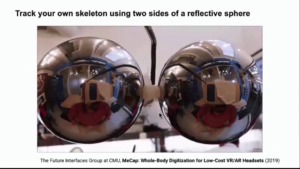

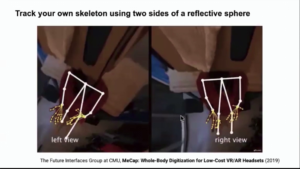

So of course this comes out of the Future Interfaces Group at CMU. And it’s using two reflective spheres attached to the Google Cardboard and computer vision to track your skeleton from inside of those spheres. So it’s like a totally low-cost way to do full-body tracking for VR.

But every time I see this I just think of the sort of do-it-yourself hand-drawn book page that could say like “Track your own skeleton using two sides of a reflective sphere.” And I think that sort of spirit is something is that I’ve noticed I enjoy in every project like this I come across.

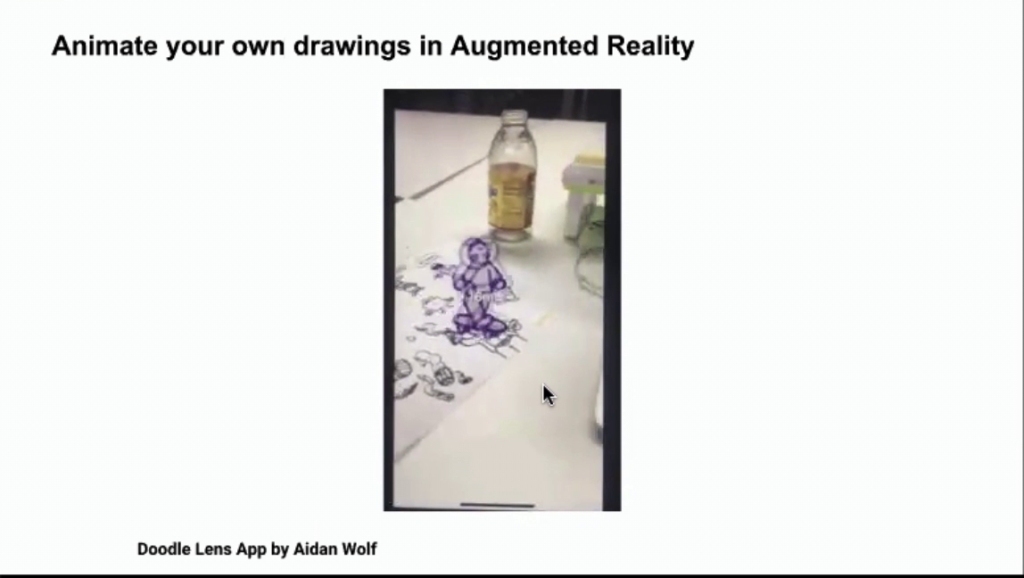

Doodle Lens App by Aidan Wolf

Doodle Lens, which is an app by Aidan Wolf is something I’ve been super excited by too, because it uses hand drawings and augmented reality to bring alive your creations. And so again, yes of course it’s that technical term. Or it’s “animate your own drawings in augmented reality,” right, like see someone skateboard.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4oprMqHqPNU

This is so great. This is something who created an experience for their daughter where they could ride their toy cat by putting a 360 camera on a stuffed animal and has a similar spirit.

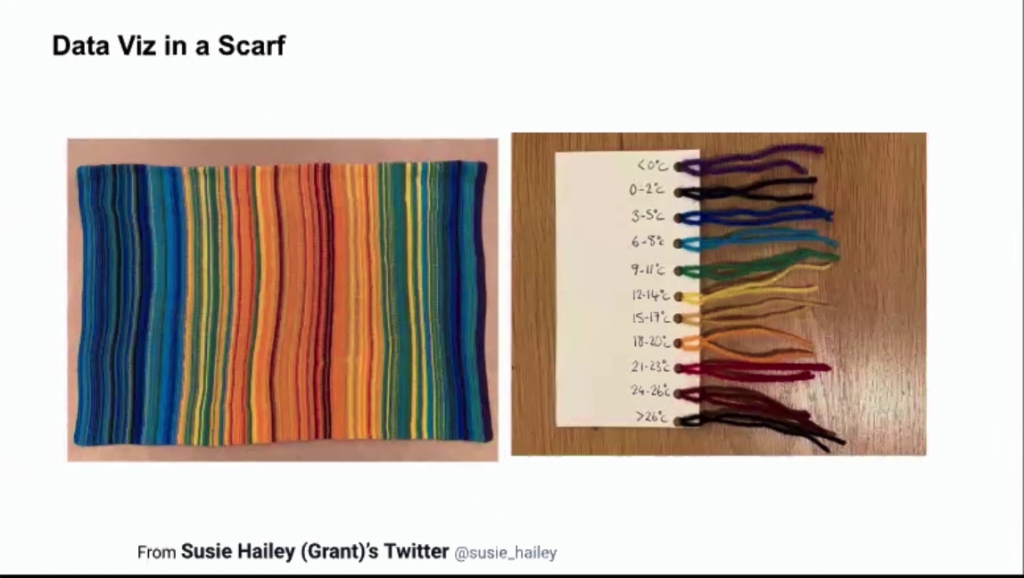

There’s great examples of data visualization in materials like scarves. This person I think used a different color string depending on the temperature and then at the end of the year had this data visualization map of what it was like that year in the weather.

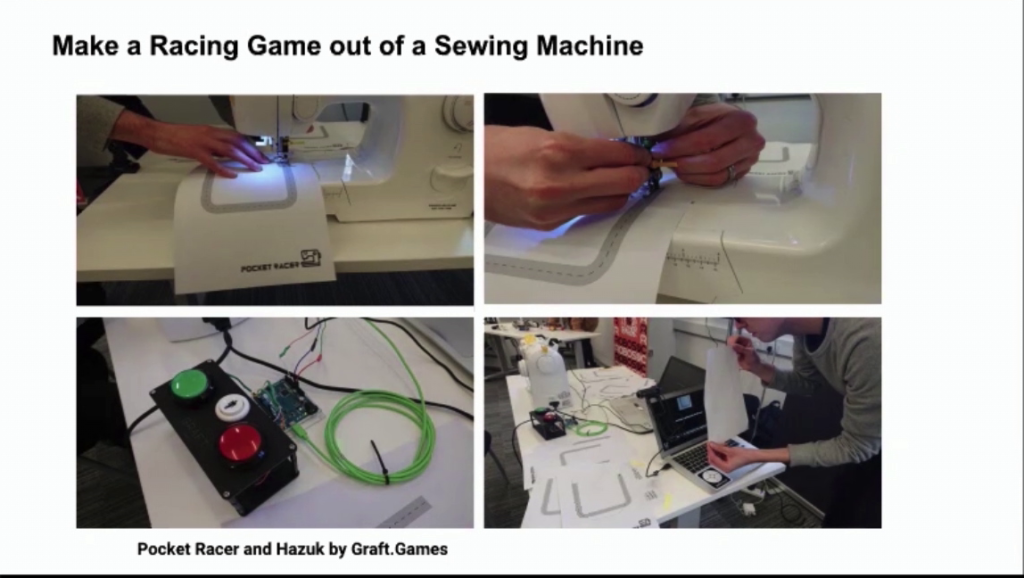

This is one of my all-time favorite projects: make a racing game out of a sewing machine. Okay, so these people essentially created these tracks for their sewing machine. And they have a camera that has an AI that’s essentially charting whether or not you go out of the “lane.” So it’s like a car racing sewing machine game, and I think this is such an excellent example of the kind of craftiness that I’m really excited about.

And so okay, now I’m totally having my cake and eating it too because in school I was involved in the curatorial side of this conference but I also wanted to share some projects that I’ve been working on with a similar sort of mindset of like, for example how to turn yourself into a paper doll, using not only arts and crafts but also using this element of technology now.

And I wanted to say a big thank you to Roxy, who I think was 8 at the time when we did this? And she helped me demonstrate some of these concepts.

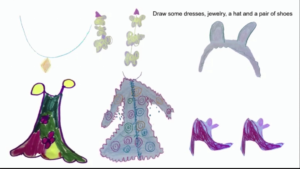

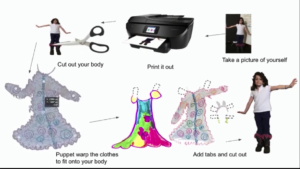

So step one would be to draw some dresses, some jewelry, some hats, some shoes. And then you take a picture of yourself, and you print it out and you cut it out. The you use the Puppet Warp in something like Photoshop to realign all of the clothing to the original form. Then you put little paper tabs then cut out each of the clothes.

And then you can start to build your own paper dolls of yourself with your drawings and have a little fashion show like we had here. And you can see she can switch out the earrings and the hats.

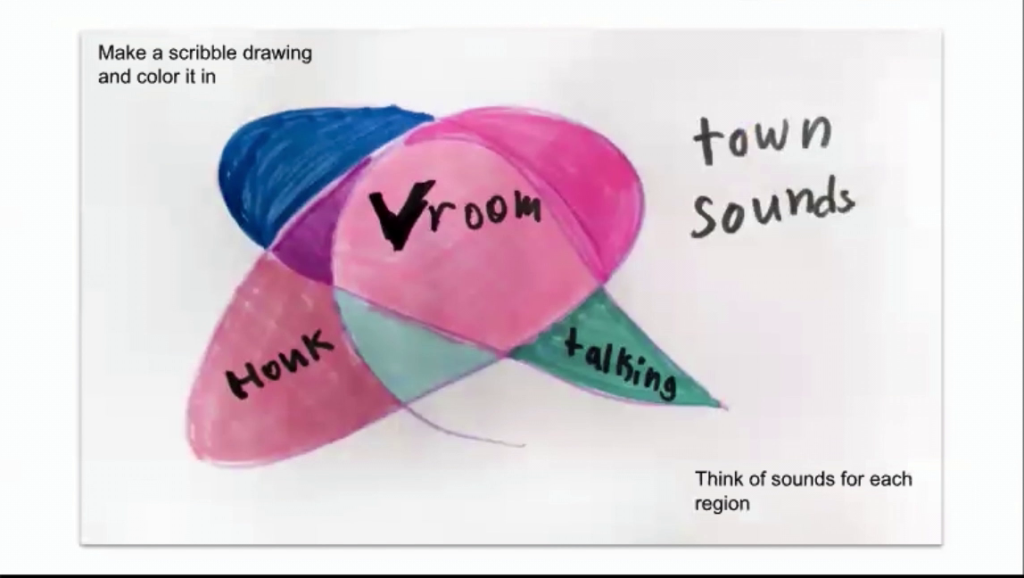

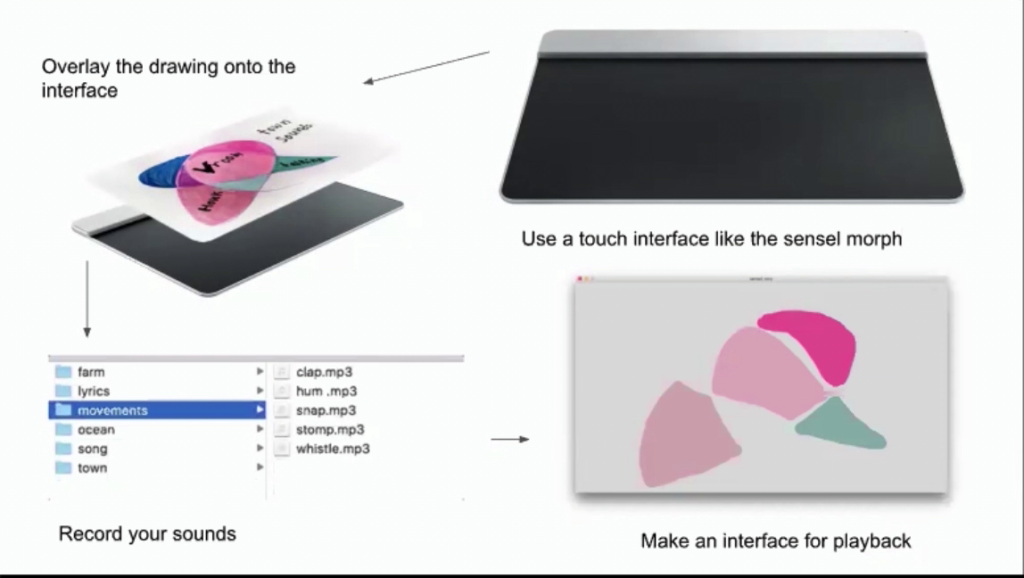

You could make a drawing instrument, for example. You can turn your scribble into a musical instrument and we used a capacitive touch interface. So I feel like Ted Nelson would be happy about that.

So the first step was to draw a scribble and then to color in each intersection of the scribble in a different color, and that was Roxy’s idea. And then think of a sound that should play when you interact with each section of the scribble. And then write that down on the scribble.

And then we were using the Sensel Morph but I think this would work with any sort of touch capacitor that you have underneath the drawing. But you basically put the touch capacitor under the drawing, and then you record your sounds. And then you make an interface for playback. We used Processing here. Then when you put it all together, you get this excellent kind of musical instrument.

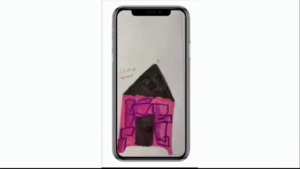

And then the last example I wanted to talk about was something I worked on two summers ago. And it was a one-day workshop for kids. And the kids in the workshop were ages 8 to 11, I believe. And we made branching narrative phone app games in a day. So this is how to do that.

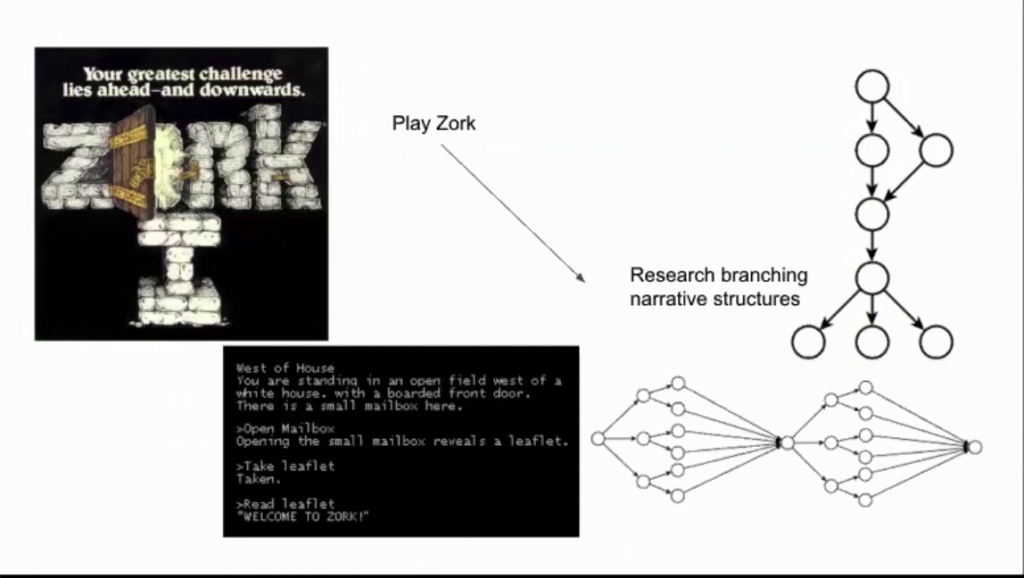

Okay, the first step was actually to play Zork. I don’t know how many of you— I wish I was on Discord right now. Write in the chat if you’ve ever played Zork. But it’s essentially a text-based narrative game that gives you a prompt and then you can use text to turn left, or go under. And it was one of the earliest computer games, but I think because kids today are so used to insane 3D graphics, the idea of a magical page that talks back to you when you talk to it was somehow a million times more exciting than a 3D game.

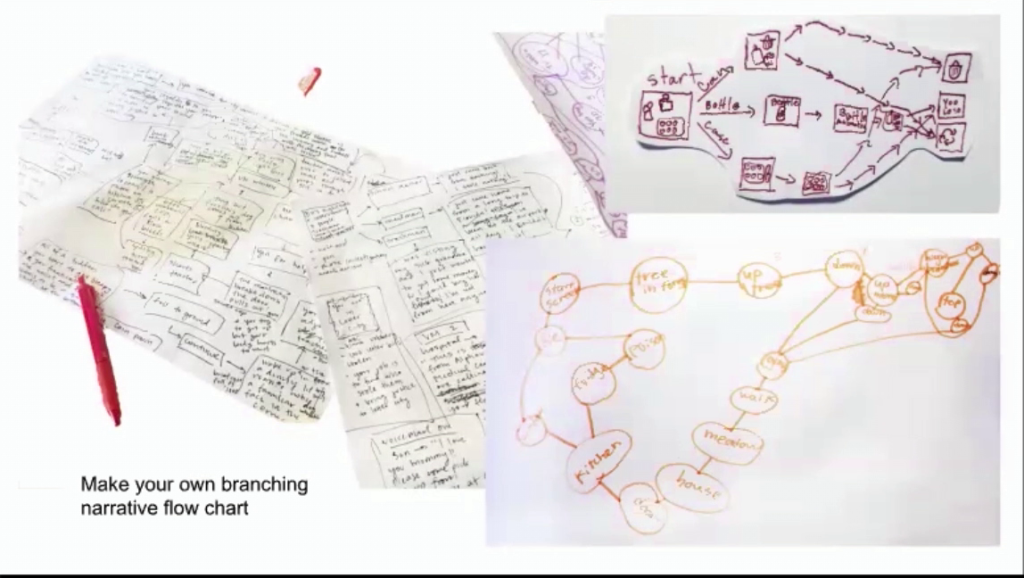

And so we played some Zork, they got their minds blown. And then we looked at branching narrative structures and essentially how different nodes in different stories can lead back to the same point. And you can start to organize a story and organize an adventure and give a player different routes.

And then the next step was they made their own flow charts for the stories of the games that they wanted to play. So for example this one, you start in the kitchen and you can either go to the fridge and pick poison. But then if you pick poison it looks like you die. Naturally.

And so they made these awesome flowcharts. And then once each node was established, they drew separate interfaces for each of those nodes, a visual representation of each element of the story that you could select on.

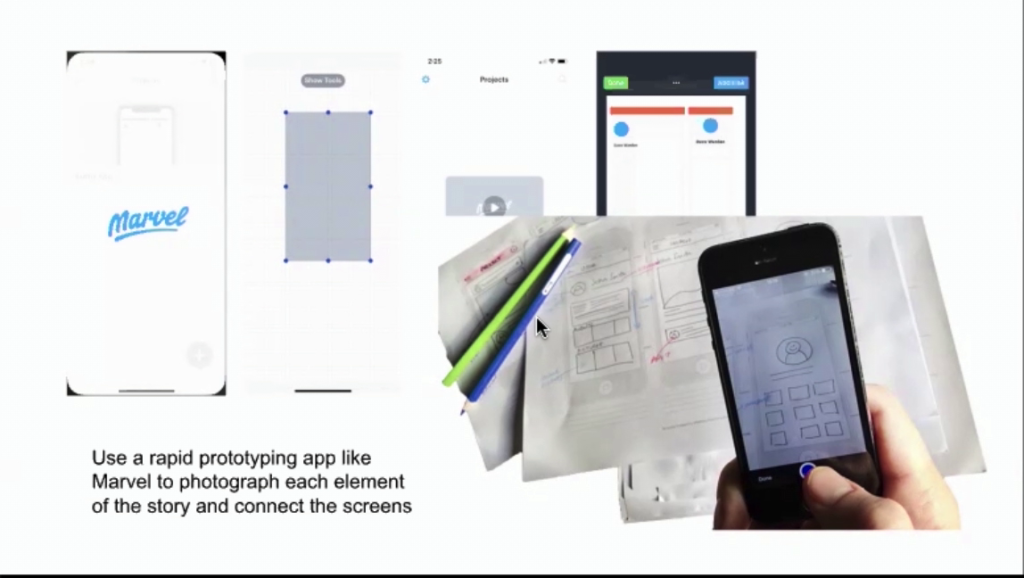

And then we used a rapid prototyping app called Marvel, but I think there’s lots of different free prototyping apps for like “wireframing.” And essentially what you can do is you can photograph each element of the story, you can create hyperlinks on the images and you can link it all together. And all the kids did this themselves.

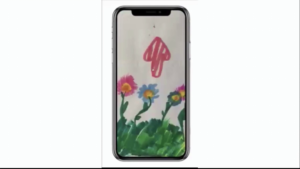

And then you can make these iPhone games. So I want to show you some of my favorite ones. And then I’ll also put in the Discord the links to these. You can do this yourself. There’s some really excellent ones.

This is the one we saw the original flowchart for. So you click on the tree. You can go up or down. Let’s go up.

Okay. You go back down. Those are your feet.

Oh I feel like I spoiled this game now. So if you click on the fridge and you click the poison…

Oh good, I clicked it for you. So I also died.

And then the other game that I wanted to show you that made me so happy was Sky Diving.

So, the pilot tells you to jump. Do you wait to jump or do you jump now? Let’s wait to jump.

You finally jumped after multiple minutes. Let’s wait to pull the ripcord. We fell to the ground unconscious. A cow lifts us and takes us to an evil cult where they want to burn us at the stake. We meet a woman. What do we do? We run away to the trees. And we live happily ever after.

So there’s lots of different ways these stories go and if you play them you can find out for yourself.

And enough about me and my work. I just wanted to give a little a little bit of insight to the curatorial process, and Lea I hope this is okay. We were originally sort of taking notes and outlining why the word “homemade” and “craft” and “materials” meant a lot to us and how to sort of frame it. And Lea gave an unbelievably interpretation of David Pye’s “The Nature and Art of Workmanship.” And so this is my interpretation of her interpretation.

But she was talking about how what distinguishes workmanship—or craft or making, in a sense—from industry is the element of uncertainty. That there’s a risk in the process that resolves itself via the maker’s discernment. So their personal taste, their subjective goals, their knowledge, their past outcomes. As well as their dexterity, so their skills. But also the tools and the techniques that they have sort of already learned.

And she is specifically rebutting the William Morris school of thought that says “handcraft” is about the dignity of the hand or some sort of aesthetic rejection of machines. But instead it’s about the process of using your personal discernment and dexterity in conversation with the material as the outcome becomes more and more certain.

And I’m so grateful to kick off Art && Code. And I’m so excited about all the speakers we have because I think everyone’s personal taste and skill set is so unique and lets them make things that are both uncertain and beautiful and in a sense homemade. So thank you so much for having me. And I’m looking forward to the rest of the conference. Bye!

Golan Levin: I’m no longer muted. Thank you, Claire. You are the one speaker that we don’t have questions prepared for because you are the person who was helping me come up with questions. But how has being alone in your isolation of quarantine of COVID changed your thinking about homemade and craft and creating things? And were you already there or has 2020 changed your thinking?

Hentschker: No, you know what, actually I appreciate the question. Because I think… I think I’ve always thought about homemade as this sort of act of love, this generous sort of thing you can do for someone else. This unnecessary but great gratitude from the other person’s style thing you can do. And I hadn’t considered how much homemade is also sometimes done out of necessity. So like whether you’re in a community that isn’t able to get something you need so you need to make it yourself. Or if you’re locked in your studio apartment in Brooklyn [laughs] and you need to make things because otherwise you’re going to lose your mind. That there’s sort of an urgency and a necessity to making things at home, too, which…I now can say that I’ve experienced.

Levin: I think a large part of what we’re going to see at the Art && Code conference is people who’re making things for different kinds of economies or non-economies. And by that I mean people who are making things for themselves, for their family, for their friends, for their communities, for their ancestors. You know, connecting with craft languages that might be thousands of years old, or which are being made as true gifts for others—as true gifts—which you know, could only come from me that could only go to you and which are not offered in exchange for anything but which are true gifts.

But also especially when people make things purely for themselves, not even really confecting it but just like making a tool for oneself, these kinds of zero-scale prototypes that are one-offs, I think all of that is within play I think in this festival.

Hentschker: Plus the festival itself is homemade. I think that was another element in it. Like we all put this together from our homes.

Levin: We’re going to be seeing a lot of people’s homes, and of course we’ve been living in this rectangle for some time. [gestures to indicate the frame of the video around his section of the livestream] And in many of the presentations we’re going to see people’s rooms, their studios, and get kind of a feeling for how they’re working now.

Well, we will break here. Thank you so much, Claire. Next up will be Irene Alvarado at six o’clock. And so we’ll see you soon.

Thanks, everyone.