Golan Levin:Hello and welcome back to our Art && Code: Homemade. My name’s Golan Levin. I’m professor of electronic art at Carnegie Mellon University and director of the Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for Creative Inquiry. And this is the third and final day of Art && Code: Homemade 2021.

The Art && Code festival series is concerned with democratizing the cultural and creative potentials of emerging technologies. We have a Discord server to support community conversations, by the way, if you’re watching this. And if you’re interested in participating in those chats we ask you to please register at artandcode.com, which is our festival web site. And you can specifically go to artandcode.com/homemade/register to receive the link for the Discord chats.

It’s a pandemic. It’s winter. We’re quarantined in our rooms. And the world is in turmoil. How can we stay vitally creative and connected at this moment? We present Art && Code: Homemade, a free online festival featuring inspirational talks by creators we admire who work with digital tools and crafty approaches to make things that preserve the magic of something homemade.

Art && Code: Homemade has been made possible by an award from the Media Arts Program of the National Endowment for the Arts, by the Sylvia and David Steiner Speaker Series at Carnegie Mellon University, and by support from generous donations to the Director’s Fund at the Frank-Ratchye STUDIO for Creative Inquiry.

This morning, it’s my terrific pleasure to introduce Cyril Diagne. He’s a Paris-based interaction designer and creative coder specialized in the application of machine learning and computer vision to human-computer interaction. He’s a co creator of ClipDrop, an augmented reality app for cutting and pasting between physical and digital worlds. Cyril Diagne.

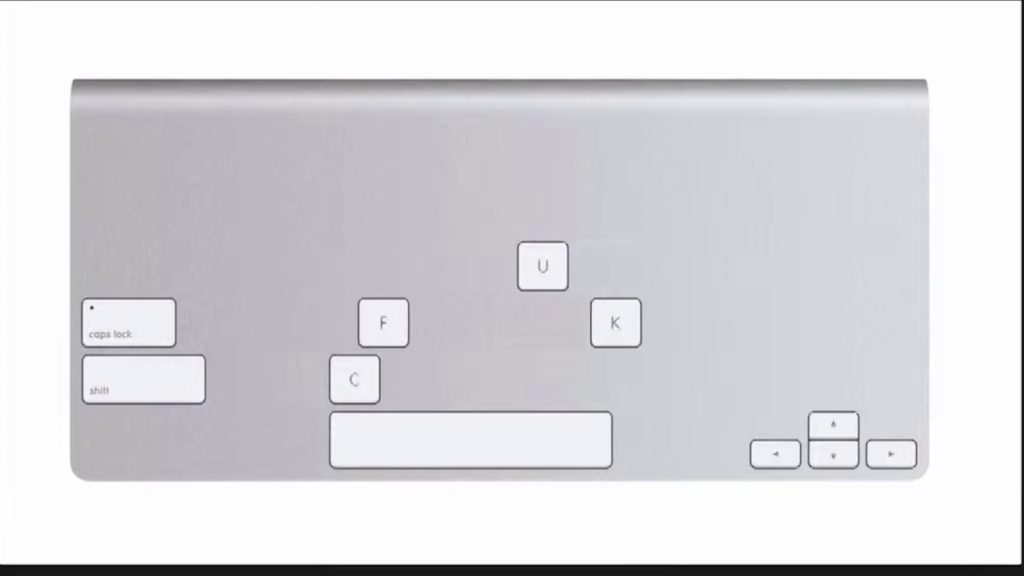

Cyril Diagne: Thank you Golan. A few words about myself. I’ve always been a bad student. This is my final grade at a French baccalaureate. I had three out of twenty, which is…really bad. I know that folks in the US use a different notation system—A, B, C, D—so to sort of give a common ground, if we apply this ratio to a keyboard this is keys that you’re left with:

So I’ve always been a bad student. This was my own native language, the French test. I got three out of twenty. I felt like okay, normally the path is you’re a good kid, you have good grades, and you have a good job. I failed at the first two; there was no way I would get a good job. So I was like fuck it, I’m just going to be an artist because I guess that’s the only thing that’s left.

So I did that. I learned how to code and became an artist at the art collective LAB212 in France. Which was a phenomenal experience. We got to create interactive installations that we exhibited around the world.

This is my very first project in the collective, called POP for “People on Pop” in 2009 with young school students from the Meknes school in Morocco. And we created this installation lets you take a pose from a choreographer, take a picture when you reach that pose, an add it to a collective video dance.

And just with the theme “homemade,” this showed how we recorded the choreography. Because I was so broke I had a blue roll of screen. And the shop didn’t have blue, they only had green. And I only had the money to buy one roll. So I had the brilliant idea “Oh, it’s no problem. I’ll just put both together and I’ll keep both colors.” Of course if you’ve done video keying you know how stupid an idea that was. And you can imagine the pain I had to key that video. But you know, at the end of the day it doesn’t matter so much. It was painful, but it worked. And it was enough to get started.

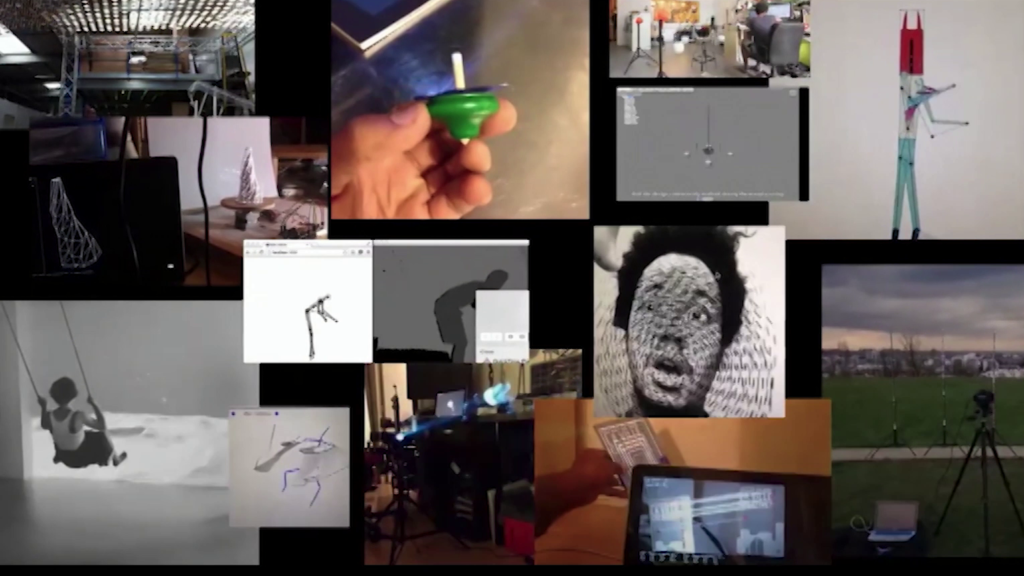

And for about seven years I just did that, really, hacking around at home. Here you can see my former home. For a quick anecdote, because rent in Paris is so expensive I didn’t have space for a lab, so I had to get rid of my couch. So I didn’t have a living room, I only had a lab instead of the living room. But it was just so fun, every day just going on about whatever it was felt that interesting at the time, not worrying if it fit any boxes, If I was going to be able to exhibit this, to show it even. Didn’t really matter. It was just about hacking all day long and exchanging ideas with the friends of the collective and seeing what could be done with it.

And strangely and ironically, just doing that eventually led me to an academic job. Because ECAL, the university of design in Lausanne, Switzerland offered me the role of professor and two lead the bachelor of media and interaction design. Which felt absolutely crazy because as I mentioned, I’ve always been a bad student. But they said actually this kind of practice is what we do in the bachelor.

So I was a bit skeptical at the beginning but then I realized that it’s true. It’s really the way that the bachelor is sort of structured and the way that students go about creating and understanding, and yes creating knowledge in the field of media and interaction design, which is an extremely hands-on, practical approach to interaction design.

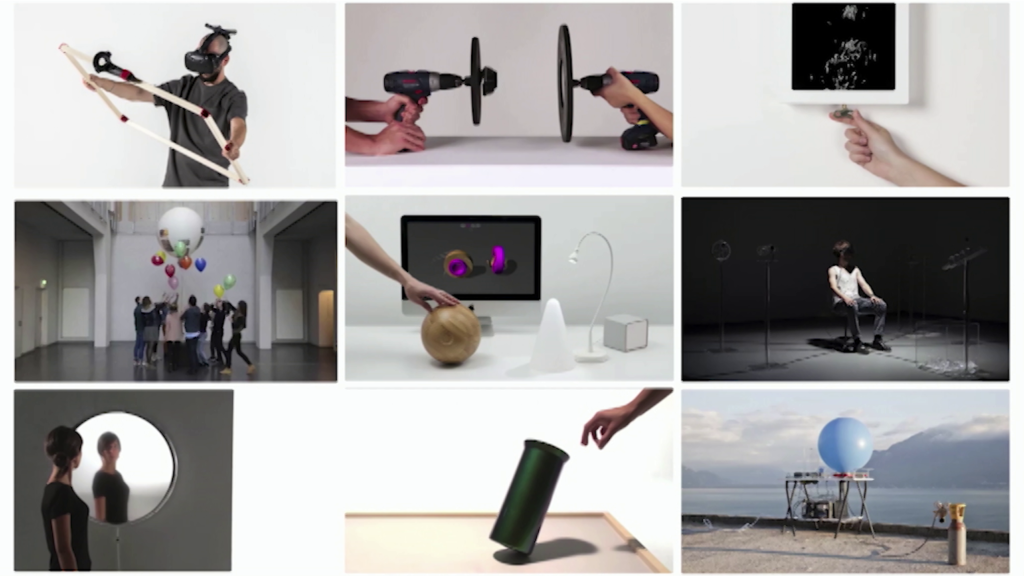

https://vimeo.com/244306001

So I had three wonderful years there. This is one project which I really liked, which we exhibited at the Milan Design Fair, which is When Objects Dream. So here, the students turned objects of everyday life and tried to explore what could be their inner life and how we could get a peek on that inner life.

So it was wonderful and it reconciliated me with academia. But I fell in love, both literally and figuratively. Literally because I got married that year, and my wife was doing long-distance. She was in Paris. And we thought it’d be nice to live together, so I moved back to France, to Paris. And figuratively because— [laughs]

Okay. That was an ambitious connection to make, I realize now. I fell in love with— [laughs] I fell in loves with AI. I think that was in 2014. I saw the inception paper, and really the same way that I felt when I saw code and I felt how it was going to change the world and completely change my life, I felt the same thing with AI. I felt the same spark again that this is going to be incredibly important.

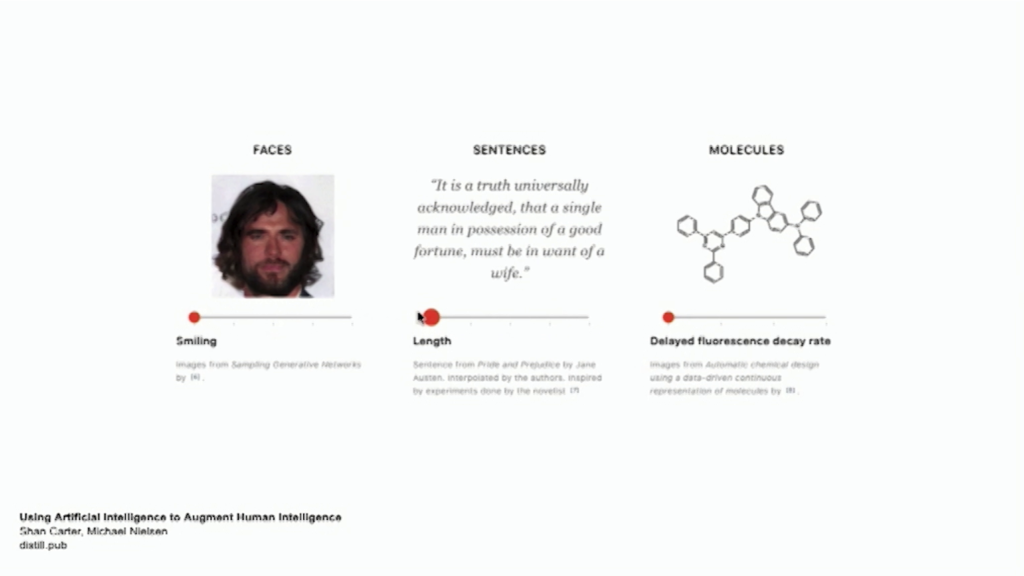

This shows an example about from a beautiful paper from Shan Carter and Michael Nielsen that sort of goes through how AI can help create more natural interaction with content and with data. So this really shows strikingly how user interfaces are going to be transformed by this technology.

And yes, I was lucky to enter a very long residency of six years at the Google Arts & Culture Lab, which I just stopped in December. And I was able to focus entirely on that, so that was really really really nice. And of course some crazy, unexpected things happened. For instance showing my hacky openFrameworks visualization of artworks to Steven Spielberg and James Cameron at TED. It was a bit random but it happened. So that was really an unexpected journey through the corporate world of big FAANG companies.

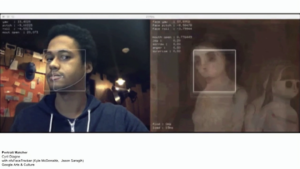

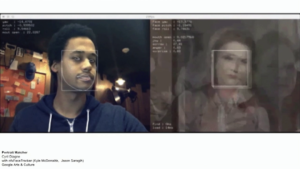

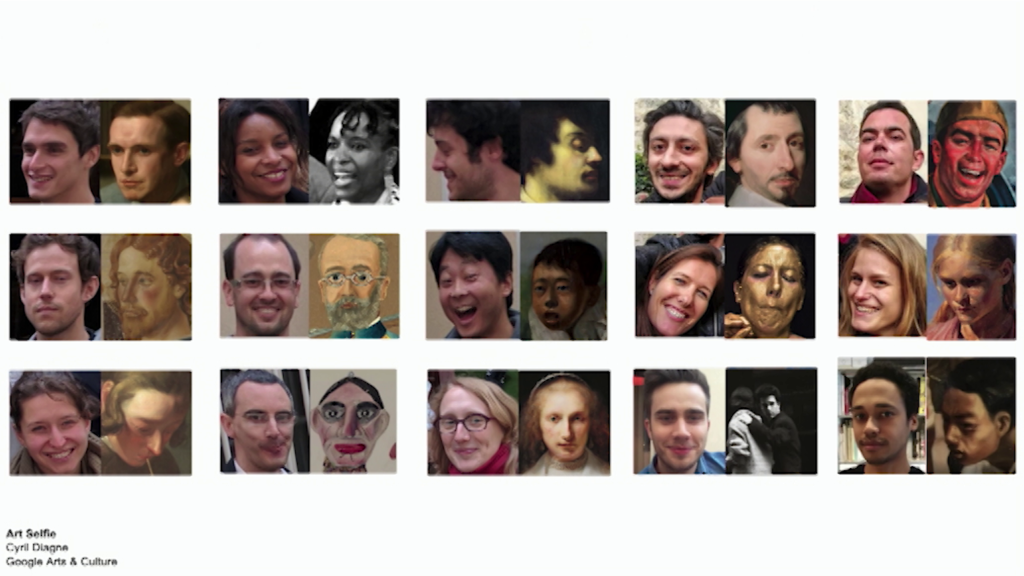

I was able at the Google Arts & Culture Lab to really apply machine learning to interaction design. This is a project called Portrait Matcher which is very similar to Sharing Faces from Kyle McDonald but here applied to artworks. And it was fun, it was nice. But it felt a little bit gimmicky, a little bit— The connection with the artworks was a bit shallow and I wanted to see if there was a way to create a deeper connection with artworks and using the face.

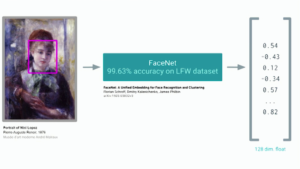

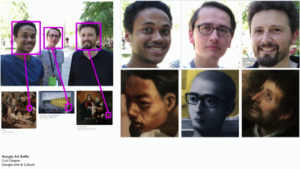

And so that was in 2015. The FaceNet paper was out but there was no public implementation of it. But being at Google, I was able to use their internal implementation because it’s Googlers who made this paper. And so it was crazy, I was able to just put all the artworks of Google Arts & Culture through the model, get the embeddings, and then do nearest-neighbor search from any image. And it was mindblowing. The results we were getting were… I was absolutely shocked by some of the connections that it would make. And not just on portraits but on any person that would appear in an artwork. So that was pretty insane.

And I realized that as I was showing it, people were sending me their pictures and they would ask me to send them their match. The more I would send back, the more would come. And at the time I had to do them one by one manually on a Jupyter notebook. And it became quite obvious that people were creating a super strong connection with whatever match they were getting.

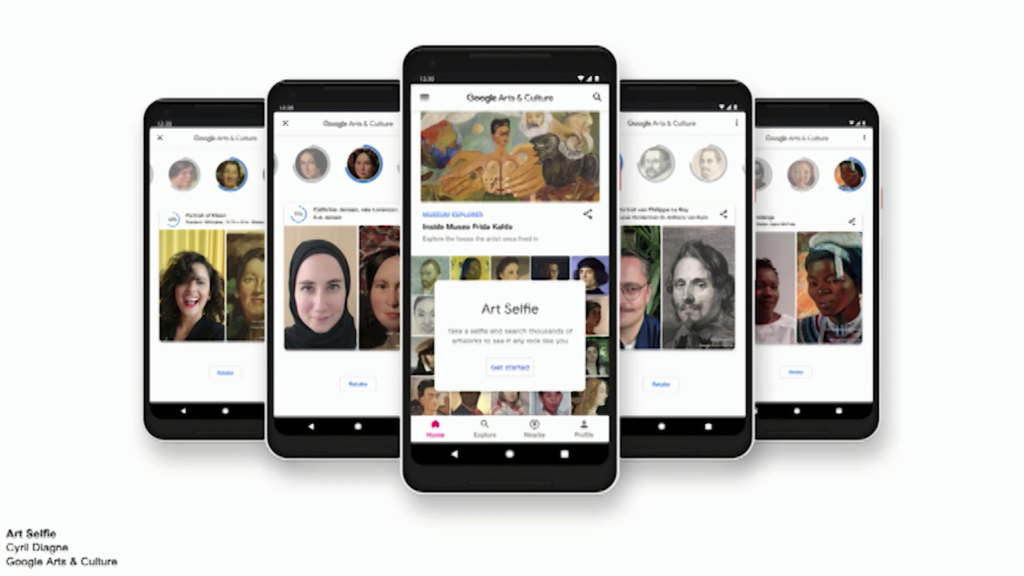

And it was quite amazing that this project actually became public and became a feature within the Google Arts & Culture app, which became viral and pushed the app as number on on all the stores. It was pretty insane.

Now, I think that was in 2018. And of course there’s been many development and it’s still crazy to me today that despite all the crazy issues that were present in that app, in that features, that it still managed to get sort of a positive narrative attached to it.

Of course, in part I would say thanks to this proxy, it helped foster the conversation on all the issues that it had. And I wouldn’t think that the same thing would happen again today. But it was sort of a lucky moment to have released that project. But anyway, I won’t go too long on this.

We did many experiments that are accessible on the experiments web site. But then I started to feel a lack of something that was really missing and was increasingly painful, which was agency. Being able to choose and to bring a project to light.

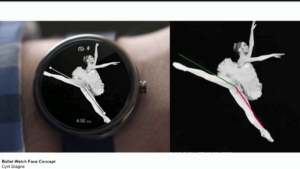

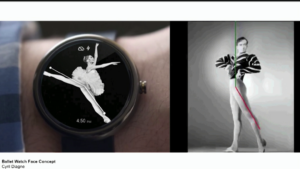

For instance this isn’t one example that I still to this day find absolutely delightful and I adore, which is a watch face that shows you dancers that match the position of the watch hands. And it was a bit strange that I felt no one really cared to make this app public. And yeah, it made me feel this lack of agency that you have in the corporate world, where of course there are gatekeepers. And it reminded me of all the issues I had at school with people that are not necessarily the people who the artwork is for but are still the ones to judge if they’re gonna get to see it at all. And I felt that felt wrong.

And so that realization coincidented with the lockdown. And it was an opportunity to force myself to create independent prototypes and research that would only fulfill my own interests.

And so I set up this sort of structure where in a maximum one week—but as it turns out most of the projects actually were done over the weekend. But there would be this hard limit of one week in order to be able not to even think if what I’m doing makes any sense. But the goal is really the sprint. Someone who sprints doesn’t stop in the middle to think if he’s going fast or not—he just goes and looks back after. This is why I don’t like the idea of a two-week sprint, which happens a lot in corporate. Because I think it sort of fails the purpose to have this sort of weekend break in the middle. So no: maximum one week, and the most important thing is no pause. You go as far as you can, you go to the end, and after you, look back and you realize oh, what have I done? This is stupid, I should absolutely not show that. Or, the opposite, you’re like well, now that it’s done you know what? Let’s just show it and maybe it will interest someone. And this exact process has changed my life. And maybe it can change yours too.

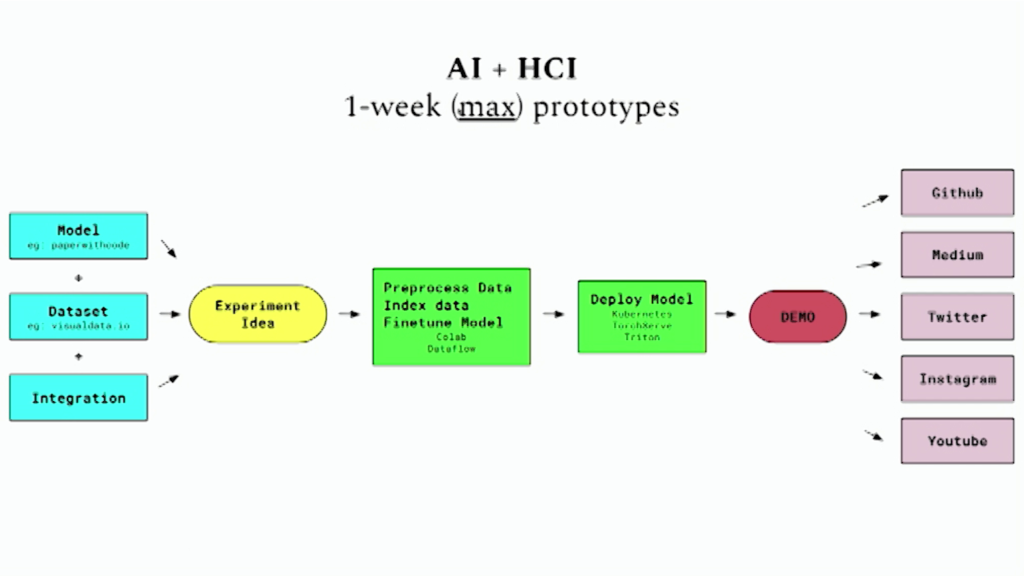

So yes, the process was very simple. Because in [tune?] toward AI plus interaction design. So you basically mix one model, and there’s plenty available on Papers With Code, Github. A dataset. So again, you have visual data, Google dataset search. Plenty of freely-accessible datasets available. And an integration. So the integration, you come up with your own sort of experience and culture. And whether it’s an app, a tool, web site, whatever. A physical object, a piece of electronics, whatever.

But then these sort of spark an experiment idea. Then you can process it and fine-tune a model using this unique mix with this unique mix as intent. And then you can deploy the model and share a demo, and very importantly, share it. If you feel like you there is no risk of causing harm with what you’ve done…at least this is what I was applying. If there’s no risk to cause harm, then I shouldn’t try to judge too hard. I should share it and let other people find maybe something that would resonate within it. including the code. Because the reason why this research existed was thanks to open source, so it was absolutely critical to make all those prototypes open source.

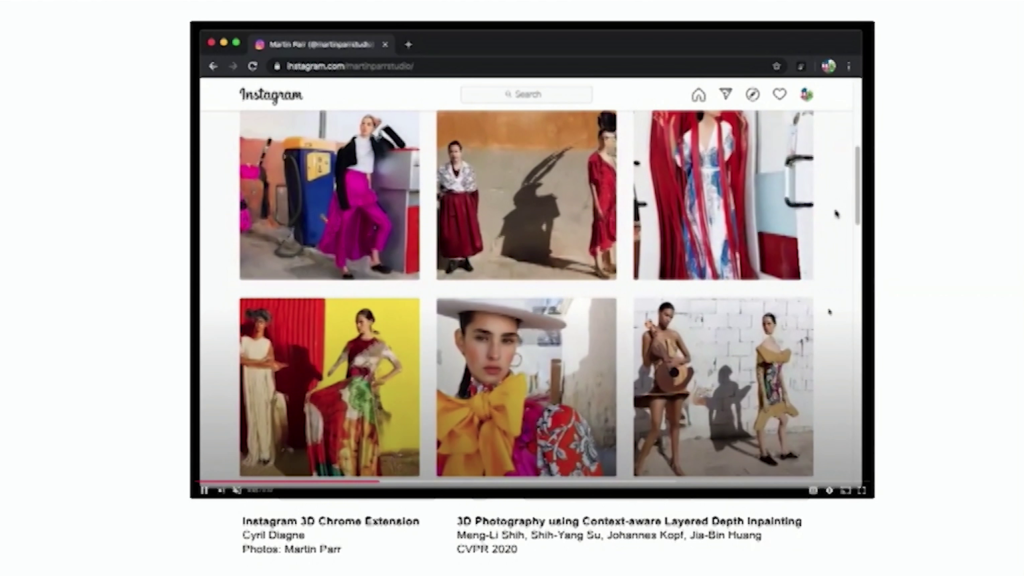

So this is one example called Instagram 3D Chrome Extension. It was done on a weekend but just applying the 3D Photography Using Context-aware Layered Depth Inpainting paper from CVPR 2020 to Instagram. So using this super-hackish way where you don’t need a GPU because it’s using Colab, you can have a Chrome extension that turns all images on Instagram into 3D automatically. So I thought this was an interesting way to sort of revisit existing content, here the beautiful photos of Martin Parr.

This was another example of a weekend experiment again, Face Doodle using MediaPipe. So here this ongoing obsession with the face and interaction, interacting with your face but here being able to just doodle and draw simple shapes and colors on your face. This just shows a little bit of how it works. But again, just using open source technologies— One of the most beautiful things for me about open source is that you don’t need permission. This is such an underestimated aspect of open source, which is that because there is no price, because there is no license, because there is no “contact us” button to get a trial… You just get the code, you don’t ask permission from anybody. You just get going. And I find that extremely powerful.

And for the anecdote, it can have such unexpected ripple effects. I mean, I don’t think Golan Levin knew he knew that he was going to change my life, me Cyril in France, when he zipped a few C++ files and sent them over to Zach Lieberman. And yet, this is just the way this code goes when it’s open source.

This is another example, Freestyle Flip Detection using Tensorflow.js running in the browser. Here the idea was to do a sort of juggling game where you could play with your phone without looking at your screen. So it was a bit short in the weekend. I didn’t finish it but I managed to do a sort of functioning prototype. But it was fun.

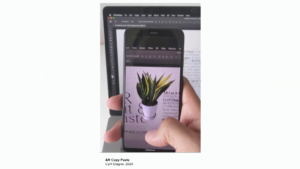

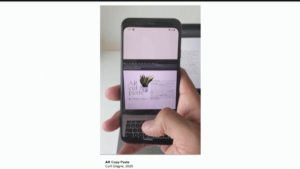

And then there was this one. AR Copy Paste. Just so you know— I’ll let you see the video. But just so you know, for me this was really one prototype like the other. I thought it was cool because otherwise I would not make it, but for me it wasn’t something particularly different from the others. It was just another weekend. I started on Friday at home using whatever equipment I had. And released the video on Sunday. So really homemade, extremely scrappy. The code is open source, you can see how badly-coded it is. But it worked. And it resonated with the folks who got to see it online.

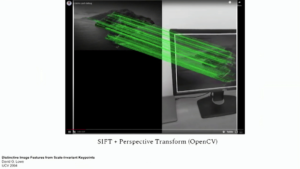

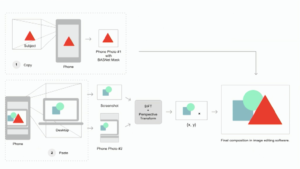

This is a little bit of how it works. So, using SIFT—I won’t go into too much technical detail, but using OpenCV it’s possible to know which location on the screen the phone is pointing at. And the prototype was using BASNet, a model from Xuebin Qin and other researchers from the University of Alberta, it’s possible to detect which pixels of an incoming image are part of the main subject and which ones are part of the background using a convolutional neural net, sort of a U‑net. And combining the two, it’s possible to create fairly easily this tool, this app, that can copy anything around you and past it directly in whatever tool you’re using at whichever location you need it.

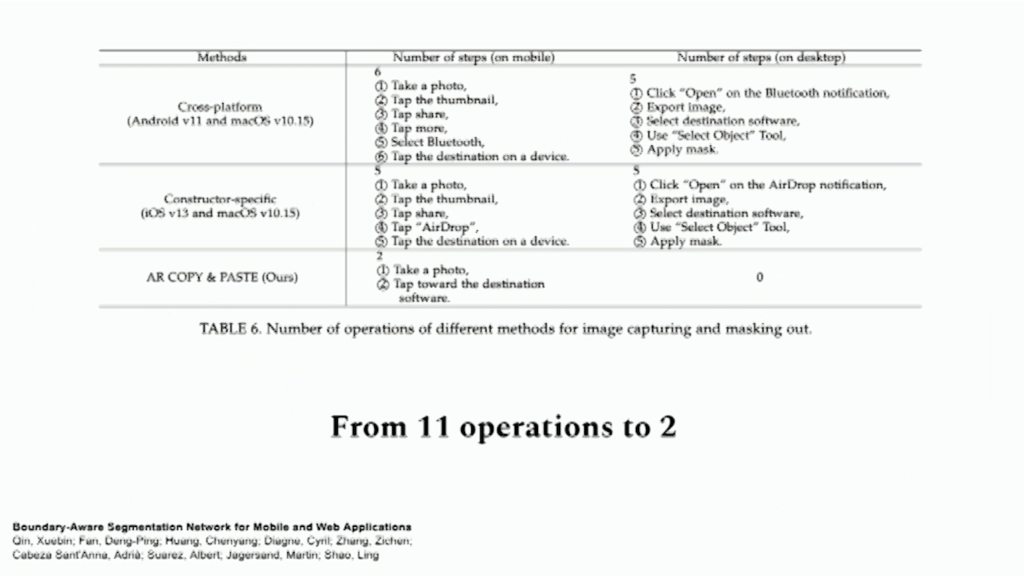

So the cool thing is that it reduces— Even in the best scenario, if you have AirDrop… So you have an iPhone, you have a Mac, you have everything set up, it requires eleven operation. With this it requires two operations.

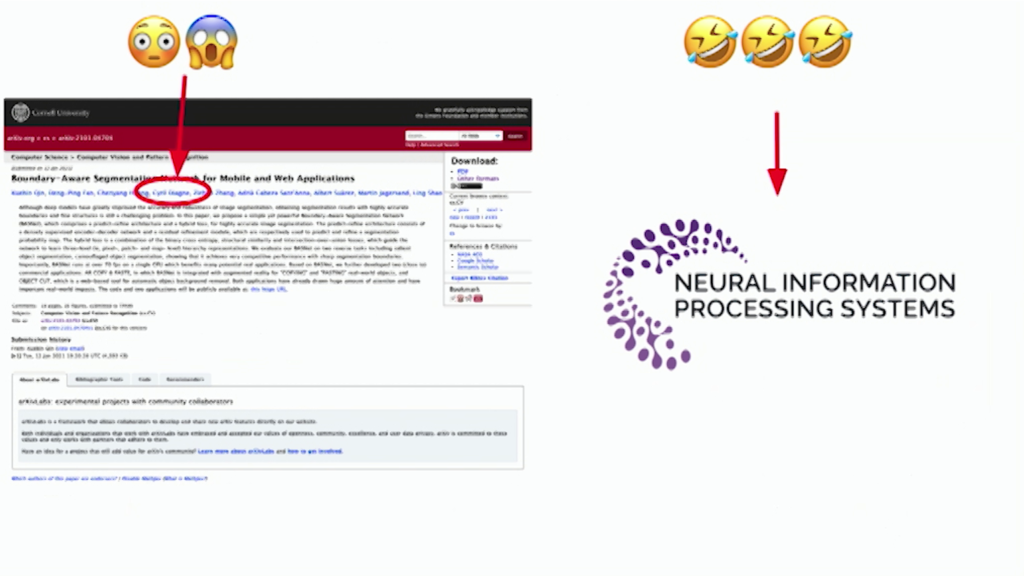

And a crazy thing happen again, which that the world took notice, and even academia took notice. Because I got to my first public paper on Arxiv. Remember, I’m a bad student so it’s a bit weird. And even invited to talk during the Black in AI Workshop at the NeurIPS, which is an extremely formal academic conference—the opposite of this one.

And so it’s really… Yes, the world reacted in unexpected ways. And another anecdote for that is LAB212, we only started exhibiting in France once we got international recognition. And we’re like “Guys, we’ve been there the whole time. What took you so long?” But it’s this thing that people will look somewhere else, maybe external, for validation. But it showed the benefits of not only being in one place.

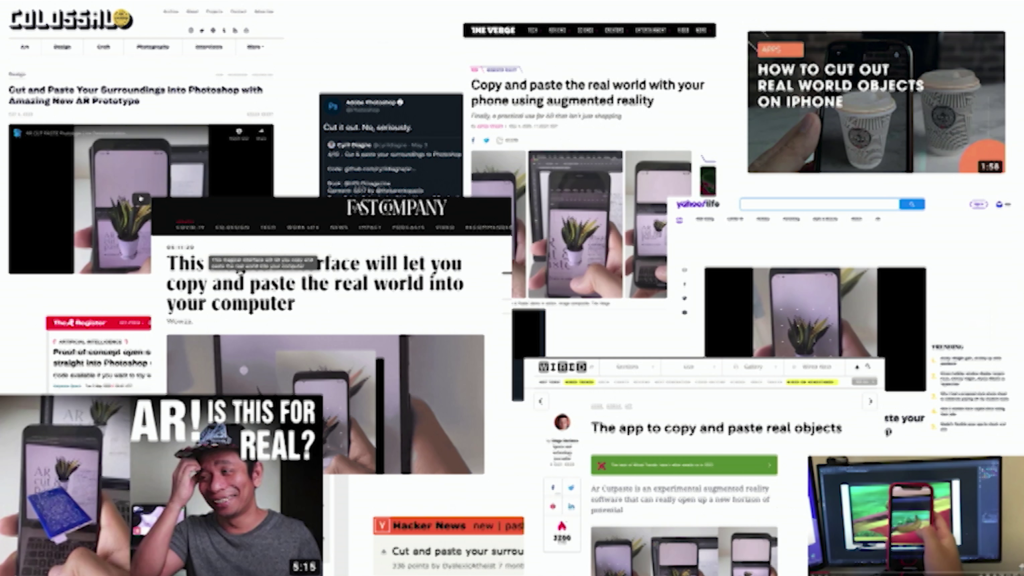

And yes, the world took notice. The prototype went kind of viral. It showed up in many blogs, and my neighbor came and was like “What’s happening? I see your name on LinkedIn. I don’t understand.” It really blew out of proportion.

working on a way to copy & paste margaritas irl #ar #ml pic.twitter.com/nhYPeLT5Pq

— Matt Reed (@mcreed) August 17, 2020

And because the code was open source people were able to tweak it and turn it into their own version. Here is one of my favorite example, someone making cocktails from the photos that they find online. So here margaritas with what I guess is a margarita machine. I didn’t know that existed but apparently. So, I found that super cool. And I would have definitely never had the idea to make that. That’s another beauty of open source.

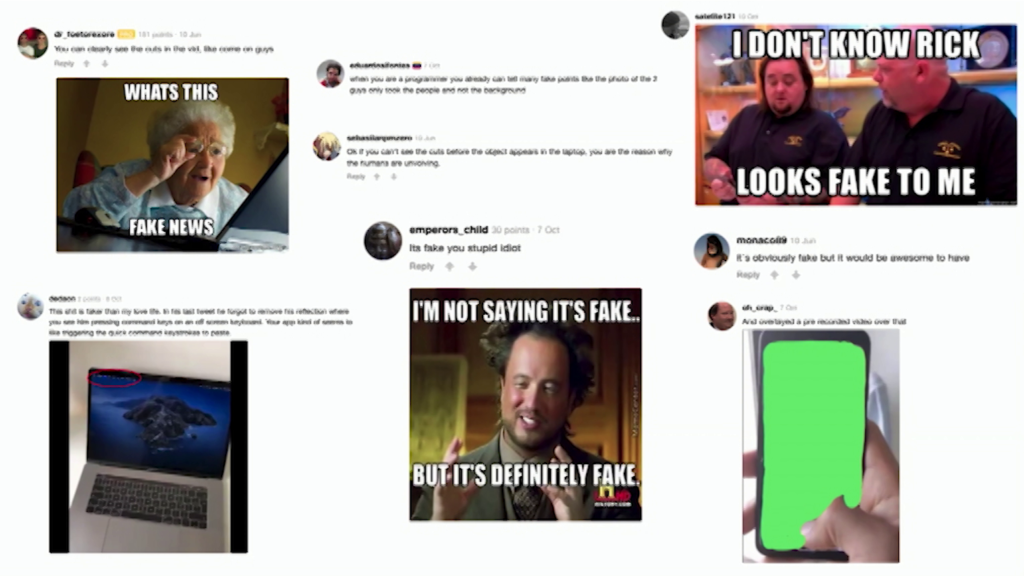

Now, with everything that gains public visibility, of course you get the trolls. And interestingly with this project, the trolls were coming with the idea that it’s fake. That it was a fake video done in 3D. And the crazy thing was, some arguments seemed to really make sense. I mean I’m like no, objectively if I had not built my prototype myself and I just read this comment seeing that video, I could believe this. It’s fairly elaborate. And so there were two routes. Either I would fight online with every single one of them and it would have led nowhere. Or, I could just make it public and have that anyone can test it and see that it actually works.

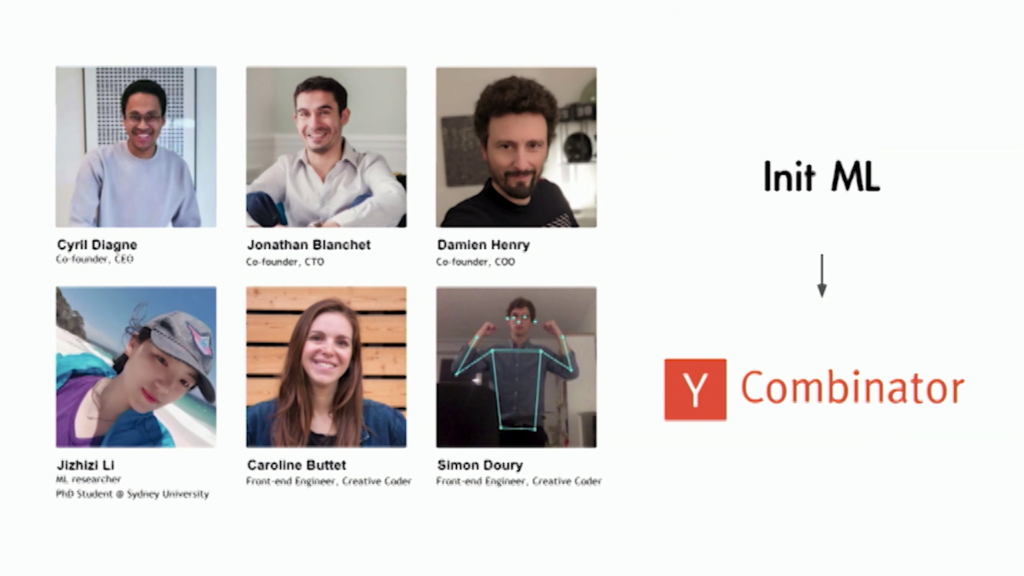

And so thanks to the help of Jonathan Blanchet and Damien Henri, two friends, we turned it into a public app. So something that started extremely scrappy in a weekend hack just because why not, pretty much, became an app that people were actually using in their workflows. And it’s being used by hundreds of thousands of people, which is still crazy to me. Because as I mentioned again, it didn’t start with a sort of grand vision. It was a small, fun prototype amongst many.

And it keeps going on, because now we are a team of six people. Because a product requires a company, because now we have so many aspects going on. We need help so we are six. And we’ve joined a startup accelerator called Y Communicator. So in pretty much all aspects we are effectively in a startup now, which is again really funny because it’s never been a dream of mine to become an entrepreneur. I would even say I would maybe a bit of a negative view of the startup world. So, it’s crazy to realize that now effectively I’m in a startup. So it’s quite funny.

And again it’s unexpected and it kind of doesn’t make sense. But at the end of the day, as long as I feel that my integrity and personal convictions are maintained, why not?

And okay, now I realize that this transition is a bit harder than I thought, with Marco Polo but I— Okay. Do I have time? A little bit of time.

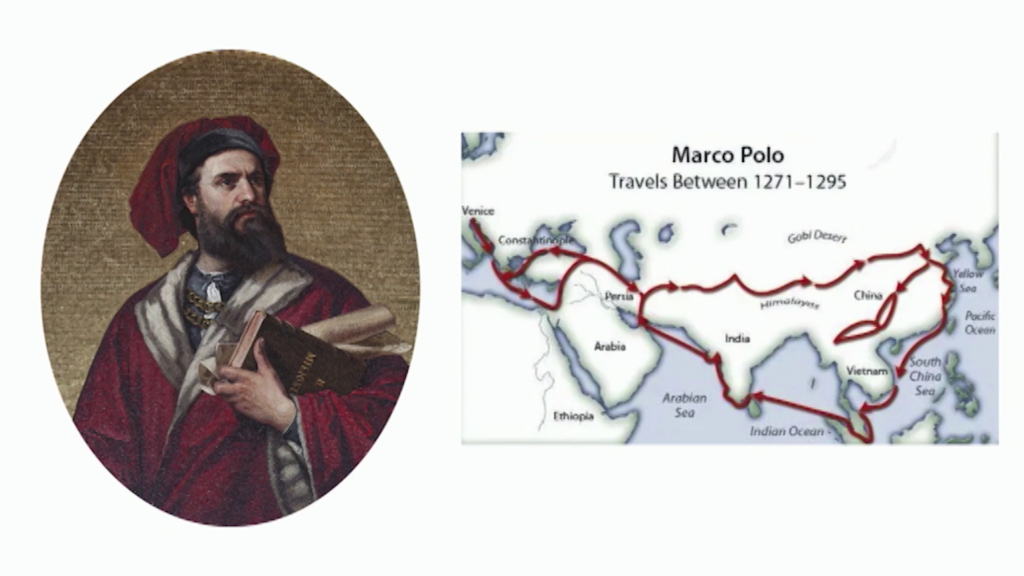

So, the idea is it’s never been that easy to change life. Our environment shapes us in many ways. Of course the physical environment—the cultural environment shapes us in many ways. And in many cases this can be limiting for creativity, for expressing ourselves and who we are. And especially during lockdown, a huge part of that environment is digital. And it’s incredibly easy to change our life digitally. You remove a few apps, you install a few others, you unfollow some people, you follow some others. And that’s it, you’ve changed lives. You don’t need anymore to go like Marco Polo, go through the Silk Road. Which at the time was an insane idea. You had to leave your family, you have to radically change so many things. But then he came back from that journey with the first writing coal, porcelain, gunpowder. So all these incredible things that he found. Back then to have these crazy stories, to have these crazy adventures, you had to give up on many things. Right now you don’t have to give up on so many things. You can entirely change your life by just switching tabs.

So, I guess my point is that because our environment shapes us in so many ways and can limit us so strongly, and because it is so easy to radically change this environment, it seems like there are a lot of incentives to try. And if that’s just one week and see how it feels, for me it has changed my life. So yeah, maybe it can change yours too. Thank you. And I guess now we have time for questions, if there are any questions. I’ll see if I can see the Discord or if Golan has questions.

Golan Levin: Thank you so much, Cyril. This was an amazing presentation, full of a lot of ideas. We’re a tiny bit short on time and there’s a lot of questions that are in the Discord for you. Many people are asking you know, how do you get your ideas, and do you keep a notebook. And you know, how do you navigate social media and virality, because it seems like you’re not just good at coming up with ideas but you’re good at coming up with ideas to have viral potential. Unfortunately I’m going to have to ask you to maybe talk to folks in the chat because we have to get our next speaker on deck.

Cyril Diagne: Yeah.

Levin: But this was a great presentation. I know I’m going to really think about this notion of a sprint really having to go within one week. I think that’s super important, because the break of the weekend changes things. Thank you so much, and everyone we’re gonna resume in just a couple minutes with Lee Wilkins. There’s a lot of clapping on the Discord. Thank you so much Cyril, and we’ll all see you in two or three minutes for Lee Wilkins.

Diagne: Thank you.