Golan Levin: Welcome back, everyone. Hi. I’m Golan Levin, director of the STUDIO for Creative Inquiry at Carnegie Mellon and director of the Art && Code festival. This is Art && Code: Homemade, and we are thrilled to introduce our third speaker and final speaker for this evening, Dr. Andrew Quitmeyer, who studies interactions between wild animals and computational devices. He directs the Digital Naturalism Laboratories in Panama, also known as the Institute for Interactive Jungle Crafts, where he blends biological fieldwork and technological crafting with a community of local and international scientists, artists, and engineers. Andy Quitmeyer.

Andrew Quitmeyer: Awesome! Thanks so much for having me. I’m really excited about getting to talk in this whole thing. So yeah, like he said I’m gonna talk today about biocrafting computers. We’ll explain more of whatever that means in a second. But hi, I’m Andy. That’s me. I look at how we can use art and technology for interacting with nature and trying to do this in the wild. And I run a little laboratory with my partner Kitty here in Gamboa, Panama called Digital Naturalism Laboratories, or our alias, the Institute for Jungle Crafts.

And I’m really excited for this whole event because I wanted to try a different talk than kinda my normal talk here, and this seems like a fun venue to do it. And instead of just showing lots of different projects and things that we’re doing with fun jungle robots—I’ll still show jungle robots so don’t worry, you won’t miss out. But I wanted to get a little bit more into the philosophy of what is going on here and why we’re doing some of this stuff. And for us this all really kind of boils down to basically the interactions between three special things in our world. This is creatures, contexts, and tools.

And so creatures, you know about these creatures, they’re these delightful little bundles of protein. They capture energy from the environment, they convert it into heat, and more of themselves.

And that’s pretty much kind of a definition of life, of living things. But one of the coolest things about these living creatures is that they come in an incredibly huge variety. They all have different super powers, and senses, and abilities, and we’re still learning about those.

And the reason there’s so many different types of cool creatures in our world is because of the variety of the environments that they evolved in. The environments around the creatures all pose different opportunities and challenges. And the creatures change and replicate and fill niches in these contexts in order for them to survive and just continue. That’s the reason why you know, in wet places things are good at swimming and have gills and breathe underwater, right. That’s how fish work. And that’s the reason why in like scary places, things are good at hiding. They have camouflage.

The key concept here is that contexts sculpt whatever is inside them. And in order to deal with these different contexts, living things have to develop tools. And for our purposes your tools are simply anything a living creature uses to interact with its environment.

It’s this bat’s little tongue for getting the nectar out of that flower. The tools of this fish are its gills and it flippers for negotiating the context of its watery environment. Or the tool of the camouflage that these katydids have developed all over.

It’s the reason why agoutis have this kind of behavioral tool of using leaves in order to hide their meals for later. An octopus can use a coconut to pretend to be a coconut. A crow can use a piece of garbage to have fun. You have tools that’re for having fun. A sloth’s unique hands help it sleep in trees.

These are all amazing different tools. And this is perhaps a broader definition of tools then you might be used to. You might be like those oh, those are senses, or those are body parts, those are instruments. Or those are interfaces. And in biology some people refer to the tools that animals have as their proxies for engaging with the context, or the extended phenotype. But we’re going to make no such distinction on the function or prominence of these things that let us reach out from ourselves. For our purposes, all tools are simply extensions of ourselves. And every way in which life can engage with the world outside of it is just another interface, another tool. This is how people look, right, when they use tools.

So this is all great. These fun little critters, running around in neat places, doin’ stuff with the tools that they have. But there’s a subset of these creatures that’re a little bit problematic. And that’s humans. You’re probably pretty familiar with these. You spend most of your time being one, I think. Humans are creatures, too. And they capture energy, and replicate, and spend a lot of their time trying to find out what makes them special compared to all the other living things in the world. Yeah I’m a human, I’m obviously so much more special. But how, exactly?

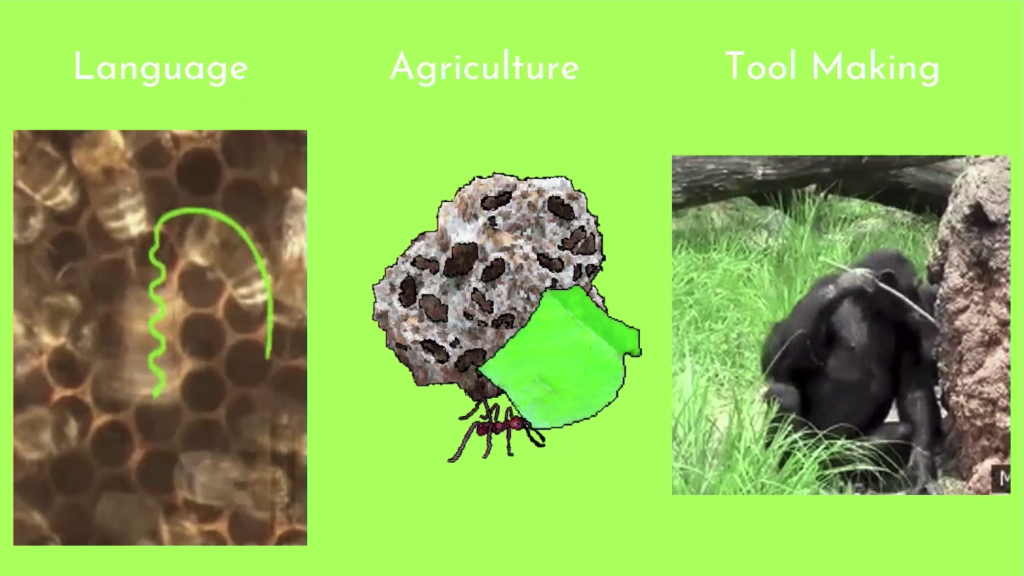

And it turns out whenever humans make a metric that tries to prove their superiority—oh, we have language, or we do agriculture, we do tool-making—we usually end up just finding other living creatures actually really already do this also. Honeybees waggle dancing. Leafcutter ants doing agriculture. Chimps using sticks as tools.

So what does make humans actually special? Well one, we’re probably the creature that spends the most time thinking about how special we are. And the second is our ability to utterly obliterate all other life around us. And this is kinda like the shortcut, the easy—the cheap way out of becoming special. You just kill everything else.

And this penchant for obliteration and exclusion that humans have, it ends up even creating two different categories in this concept of what a context is. And this is different place where things could happen. We now human spaces and wild spaces. Human spaces means basically other creatures aren’t allowed in. No, agoutis, you stay out. This is a human zone.

Or, if we do allow other creatures, other lifeforms, it’s only the ones that we can really designate and control ourselves. And by defining human spaces like that even then forces us to invent this concept of nature.

And this is all based on this idea of exclusion, exclusion and control. Human spaces are where we make all the decisions. And wild places, or sometimes “natural” places, are those where we never had control or we’ve given up control, some kind of frame of reference. And of course no space is perfectly one of the other category. There’s a spectrum of exclusivity, and the type of exclusivity depends on your different human cultural background and stuff. You know, some people might have a super clean house, it still gets infested with ants. But it’s the spectrum of exclusivity that humans do which is kinda weird.

And now we have this brand new tool: computers. They can run billions of commands that we tell them to do. And it’s the first time in human history we actually have a medium we can tell do stuff and it does stuff. But that’s super dangerous, right? Because the things that we do as humans already tend to be horrible. There’s my little Roomba just going around exterminating life.

And this kinda brings the main problem of our little story about creatures, contexts, and tools. You have humans, and they’re very powerful and self-centered. And they use their tools to modify their environments and exclude and obliterate other lifeforms. And I want to help people figure out ways to give up some of this control. And my hope is that there’s something in this new programmable medium that we can use to somehow build connections with all the other lifeforms around us rather than reinforcing separations.

And so, my initial thought was okay if I wanted to know about other types of lifeforms, I should go hang out with field biologists. And what’re field biologists? Well, they’re a type of human so I’ll already be a little skeptical. But they’re really interested in what other lifeforms are doing. And they have different tools that they try to use and extend their body with. And because they’re field biologists, they try to do their experiments in places where these creatures actually live.

And doing their research in wild areas, it keeps the creatures in their own environment. And the goal of this is it reduces unknown variables that might come up if we had instead taken this animal out of its environment, separated it from that environment, and used it in a human space like a laboratory.

The other side of this field biology is by working in the field it also immerses the scientists in these very foreign, not-that-human of spaces. And it lets their senses and tools be sculpted and honed to all the details of that surrounding context. We’re trying to actually let ourselves be changed to help understand these animal types of environments.

But that also means these field biologists are confronted with the huge task of how do you make sense of anything if you’re actually going to be trying to study everything, you know. The context in every possible thing and the infinite number of variables around you that you have to deal with.

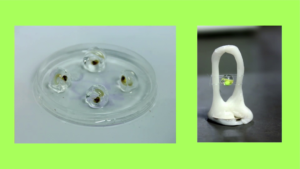

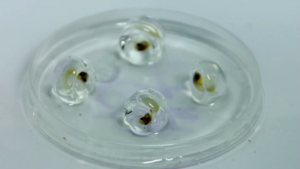

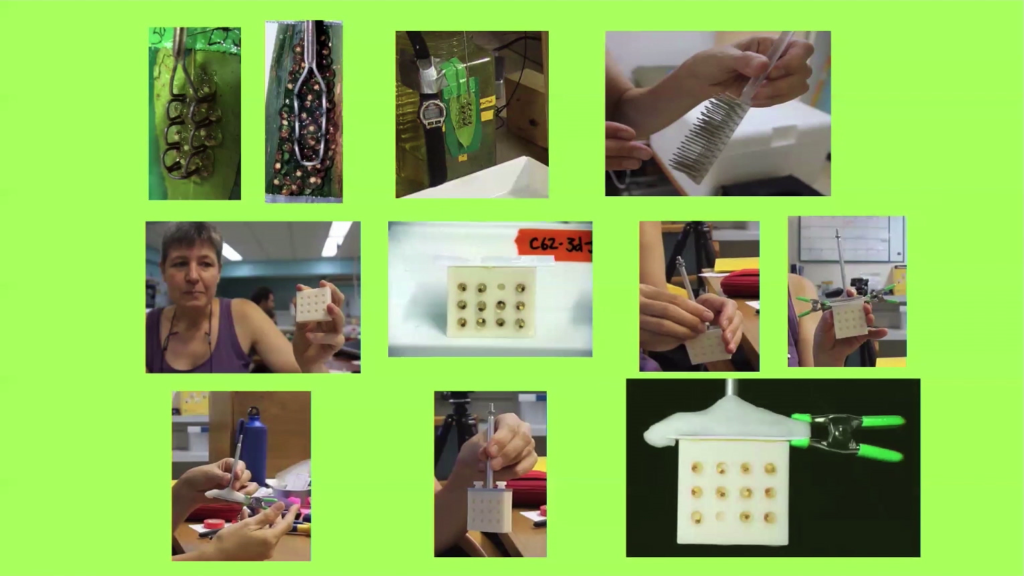

And one of their main responses, these field biologists, is to get crafty. So field biologists are usually confronted with—from a human point of view—very strange tasks. For example, I want to make a bat go through a three-dimensional acoustic maze. Or I want to see their tongue movement when they pollinate flowers, so I need some sort of crystalline faux nectar flower surrogate.

Or, I want to hold a single tadpole egg that I can rotate and vibrate, and also the holder is optically clear. But there’s usually not that many ready-made tools around just for these cases. If you go to Walmart and you ask for a tadpole holder that’s optically clear, they might not have what you’re looking for. And like noted frog biologist Dr. Karen Warkentin says, she studies frog embryos. That’s not something that there’s standard tools for.

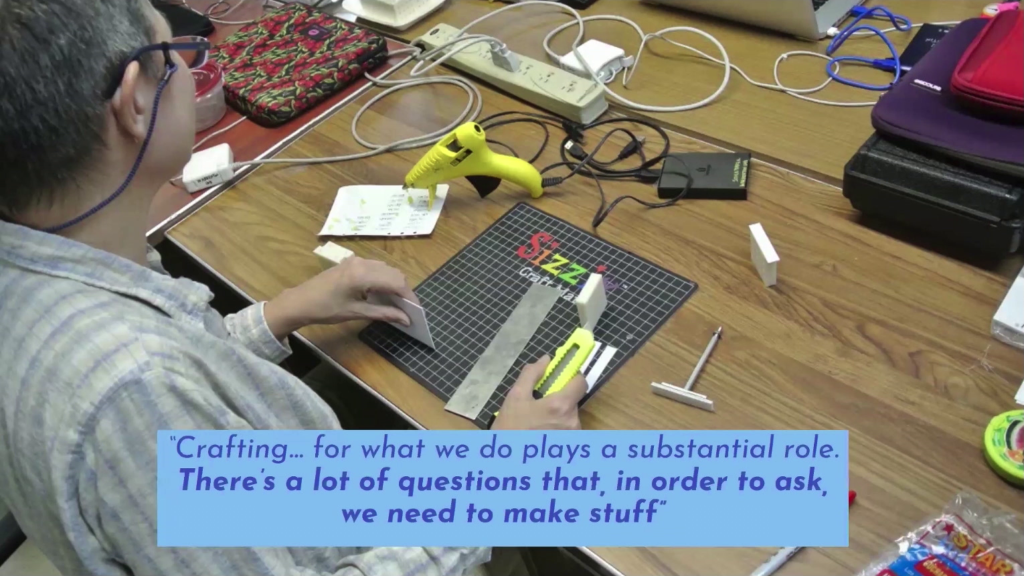

So, they have to get crafty. And these biologist usually have to end up then crafting their own tools. And these could be tools crafted completely from the ground up, like these very meticulous túngara frog models made by Barrett Klein for these frog robots that they use. Or by modifying industrial, commercial, or natural materials, kind of hacking them together to make new animal interaction tools.

But, they often have to craft their devices themselves. That’s kind of the bottom line. And the reason about this crafting is like Dr. Warkentin notes, is because there’s a lot of questions that in order to ask, you actually have to make stuff. So you have to make stuff in order to ask a question.

And the really neat thing about that is for scientists, for these field biologists, the tools they create actually are the embodiment of a question. Which I think is kinda lovely. But as we all know if you’ve crafted anything, when you’re making something it doesn’t always come out exactly how you originally thought. Like oh, things change. And those changes are also going to change your question at the same time. So in order to maintain the integrity of the question, you have to figure out ways in which you’re crafting your tools effectively.

And so, the crafting process, this “biocrafting” as we might call it, it necessarily includes doing things like rapid iterations, where you’re sculpting and refining these scientific tools to the exact specification of the creature, the environment, and the question that you’re asking.

And then at the same time, doing this type of work on site is very important. Dr. Warkentin here notes again in interviews that we had with her, if every design requires a trip to Boston and her field site down here in Panama, it’s gonna take forever and the tools are never going to get quite to the point where you want them.

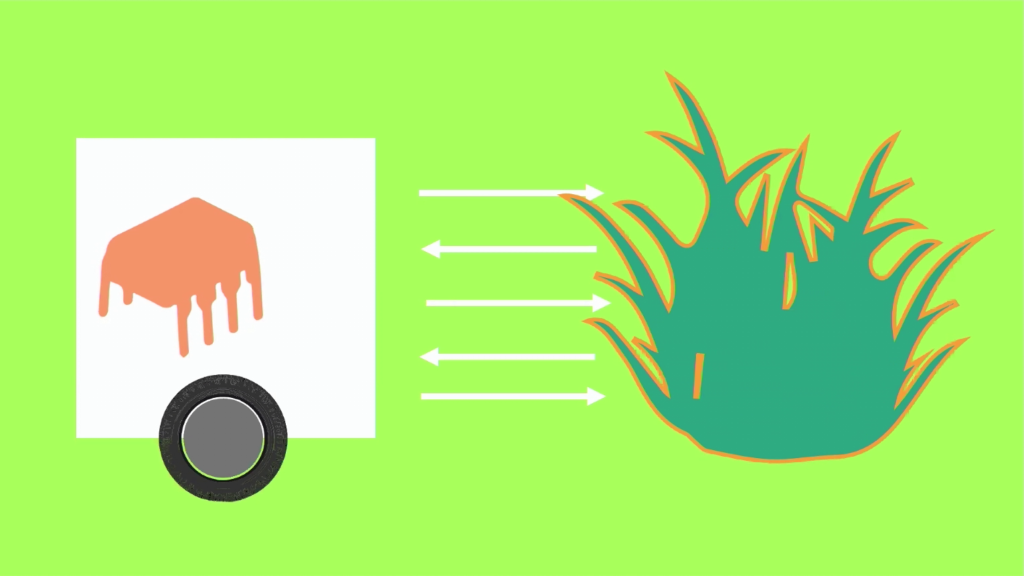

So this way of biocraft, of rapidly building your own tools, iteratively, and on site, is done so in order to ask the questions for your environment. It’s all done in order to maintain this research integrity. And the reason why this works is because tools are bidirectional. And what does this mean? It means that…you know, this is kind of a weird concept but we often think of our tools as things that we use to change the environment. “I am a human. I have a hammer. I smash things. I’m in charge here,” right?

But like the classic idiom goes, to the person who has a hammer everything looks like a nail. Your tools actually…they don’t just allow you to change the environment, they change you. They change us, and they change the way that we see the world, we interact with the world, they even change our whole bodies, and our senses. So, hammers let us squish things, yes, but they also turn us into thing-squishers. This is my persona now, a thing-squisher. The leaf that the agouti was using to hide its food, it’s also using the agouti as a tool for planting the babies of this tree that it’s from.

And the tools that we’ve created somewhere, they all take on these characteristics and assumptions from the context in which they were built. And so by crafting and customizing their tools at these field sites instead of at studios far away, or laboratories far away, biologists are actually working to help their tools become better-suited to the contexts and the research problems, and their own original curiosities that came up in these field sites.

But now there’s a whole new type of tool that scientists can incorporate. And perhaps it’s not a tool but it’s a creature, right? Computers are a little funny. Just like a living creature, computers can sense things. They can create stimuli. They can react to their environments.

And we call when you have senses and reactions to things, those are called behaviors. And whether these behaviors come from natural systems or digital systems, by putting together these senses and reactions of this new digital medium that we have, it can help us understand the designs of both the creatures and the computers.

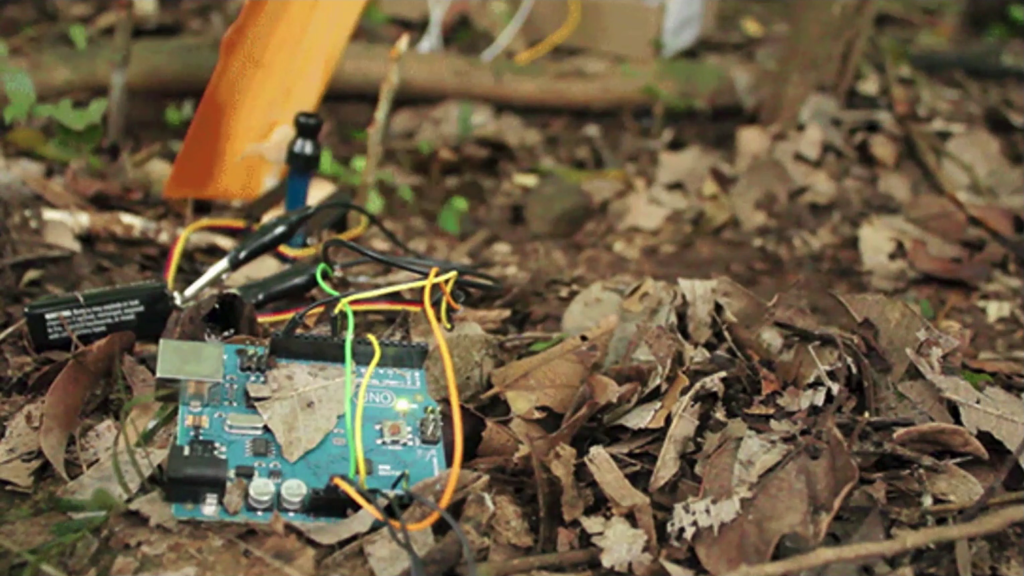

And just like any other tool, though, these computers are not developed in a vacuum and they’re not being used in a vacuum. They take on characteristics and assumptions from wherever they were created. And unfortunately these powerful new digital tools we have, they’re largely developed in climate-controlled human-oriented environments.

And the tools that we develop, that means that they’re mainly getting feedback during these iterations from these environments around them. And we have to kind of imagine like, oh will this work in the field? I don’t know. We build in all these assumptions about what we remember about the field, and we’re not actually iteratively testing them as much.

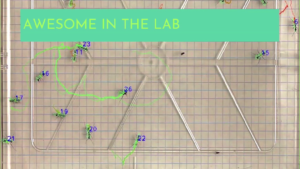

What’s more is, if computers then present incredible new abilities… Wow, I can track every single ant in the laboratory. And they work amazing in the lab. But they’re not as robust to take on the challenges in the actual world like oh, it doesn’t work because trees are round, this suddenly means in general that it ends up being the scientists and their organisms are the ones who’re forced out of the original environments and have to go into the computer-friendly human spaces.

This is them moving over. Goodbye, field. And this isn’t where the field biologists want to be. And it’s not really that great for their science. And we see this in many other disciplines, wherever computers are introduced. Computers can bulldoze the original goals of research and instead reframe everything in a way that better serves computers. You’ve all seen this like, “Oh well, we need to do this because the computer wants it this way.”

And my thoughts are here just you know, maybe it’s the computers and the way that we craft computational tools that actually needs to change instead of the people, instead of the environment, instead of the living creatures.

And so part of this is kind of a proposal to…let’s develop wilderness tools in the wild. Let’s build computer stuff in the wild. And of course, that’s the whole reason field stations exist in the first place. To have human space right next to a natural place, and let the scientists kind of shrink this gap between lab and field and kind of speed up these iterations that they can do.

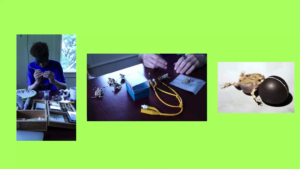

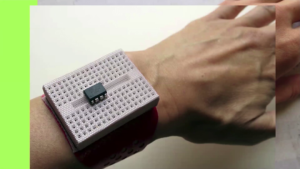

And I thought we should have the same thing for working with digital technology and nature for using computers. Get them into the nature. And so I made some initial “digital biocrafting stations,” we called them, when I was a PhD student. Which was mostly me just squatting in parts of the Smithsonian’s field station here in Panama and setting up my own little soldering stations and stuff and hiding them when we had to. And we kept developing this. And we’d run workshops about things, doing kind of basic interactions between creatures and computers.

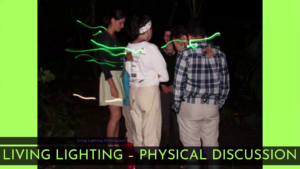

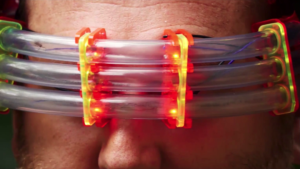

Like wearable interactive firefly outfits.

Or sending messages through Morse code messages through leafcutter ants with Arduinos.

And this even grew into a full-time facility where I’m at right now. We have a house in Gamboa right next to the Smithsonian and the rainforest, and we’ve converted it into kind of an art/science/makerspace with construction shops, 3D printers, laser cutters, prototyping workshops, electronics labs. We have a little art science gallery that’s where I’m in right now. Documentation equipment.

And we help run field courses, do field site maintenance for the scientists here. This even includes trying to repair these ancient bridges that’re here for the scientists to get to their field sites. Kind of harsh conditions.

And even doing fun projects like making wearable ant farms and building interactive enrichment toys for local animal rescues nearby.

We offer long and short-term residencies when there’s not giant global pandemics everywhere. More about that at dinalab.net.

And the most important part, though, is this lab is right next to the jungle, and the forests, and a place where there’s these amazing, wonderful creatures.

But what if we want to get even closer? And so that’s where we started getting into like, I’m gettin’ hungry. I need to get in these natural environments more and more. And so I was thinking of how do we push this idea of crafting in the context even further. And I was trying to think of how we could shrink this lab and bring it closer to the field.

So we have things like mobile studios, where we literally just try to put the lab into a box and drag it out with us like a big trailer. So for example we’re working on these portable rough-and-tumble jungle trailers with the local sustainable architecture company Cresolus here. And the idea’s we could loan them out to scientists and they could stay in the forest at their field sites as long as possible.

And they even float. We’ve even made other floating mobile lab spaces, such as the Boat Lab, the community-made modular floating hackerspace for community science projects we used to kind of draw attention to an endangered coral reef in the Philippines.

We also when I had some students, brought them on sailboats that we converted into floating makerspaces to build different types of scientific tools.

But there’s still some places that ships and vehicles cannot go. And so we can try to shrink this lab even more and push this into the idea of carryable studios. And so these are ideas really pushed forward by things like hannah perner-wilson has made these amazing mobile studios that unpack and can store all of your electronics and devices all together that you can then carry on things we call hiking hacks, where we would take a group of people. We would carry all the tools that would normally be in our lab, go to a scientist’s field site, and we’d live and work out there, designing and reflecting upon, and documenting as many different projects as we could while trying to stay as immersed as possible in this field site, while we’re trying to make different types of probes and tools for experiencing the nature around us.

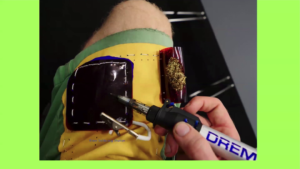

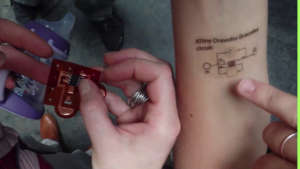

But then, what if you don’t want to carry it? What if we push this idea even further and it’s just part of you? This is this idea of wearable studios. Again really pioneered by hanah perner-wilson’s incredible designs. We realized you can never really rely on anything in this world except that like, wherever you are, you’re at least going to be there. So if you turn your body into your studio, and your body into electronics work surfaces that can be directly incorporated and rapidly prototyped upon.

Having different work surfaces, solder on your knee, keep your information in tattoos on your body. You’ll have quicker access and be able to go places you wouldn’t be able to with a trailer or even a large bulky backpack.

And for me, this is kind of the ultimate goal here, where all of this leads. A future where one’s body, laboratory, and field site are all one and the same. And we can be walking, pondering, curious naturalist cyborgs with our different hyphae reaching into every nook and cranny around us and connecting us to the things around us. And so that’s most of what I wanted to talk with you about. We can answer questions and stuff. I have lots more random other examples of stuff I can show but yeah, I would love to just get feedback, and questions.

Levin: Andy, thank you so much. This is incredible. I have a bunch of questions stacked up from both the chat and also from my own thing here. But first I actually wanted to bring the attention of the audience to something that you contributed to and also many of the other speakers as well, which is the Art && Code zine which is downloadable from the Art && Code: Homemade web site.

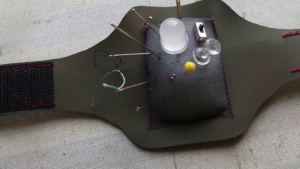

And in particular, you contributed this thing called the Touch Tire, which is a plan for a kind of capacitive sensing tire. Apparently you used the metal mash that’s inside of the rubber tire to sense the presence of an agouti and then as the result of an Arduino sensing this agouti, I guess the agouti gets a shower or something like this. Can you tell us a little bit about this particular contribution and how it arose?

Quitmeyer: Yeah, definitely. So when you’re working with a lot of wild animals, like at the animal rescue we have an agouti and we also this 400-pound tapir. And so usually electronics, like I was mentioning, they’re not usually that durable. They’re kinda wimpy. They don’t want to be out in a rainstorm. They don’t want to you know, get chomped up by a tapir. And so it can be hard to think when we’re doing interaction design, a lot of the normal interactions we come up with—they’re like, “Oh, this button we’re going to press,” that has a different letter on it or something like that doesn’t really work for a tapir. Or an agouti. And it also needs to be rained on and all this kind of stuff.

And so I was trying to think of what’s the simplest interface we can use that people would have access to that would be really rough-and-tumble, and durable enough to withstand a lot of abuse but still allow for lots of different kinds of interactions. And I had this realization that you know, there’s old tires all over the place. People have access to ’em. And I realized that tires I guess often have like a metal mesh inside. And so you drill into it, and you can just put a chain through it, something also indestructible but metal. You can then send this chain, put it around a tree, send it over somewhere, connect an Arduino to it safely away from the tapir. In maybe a climate-controlled space or something like that. And then you have this thing that you can really beat up and chomp on or get rained on, and you can still get some data about who’s interacting with it in different ways.

And from that, at our animal rescue we have some showers that the tapir really likes playing around in. Or you know, it hides their leaves in different places. Different animal enrichments to keep their brains going. We can trigger all those different kinds of things like that. And so this is a kind of thing that I’m working on right now throughout this upcoming spring. I hope to actually get some of those going. So I’ll be posting updates whenever possible.

Levin: I’ve got a couple more questions. So one question is these workshops that you direct. I realize we’re in a pandemic. But can you talk more about the residencies and workshops that you direct, and sort of who comes to them and you know, is this something that people apply for. Tell us how these happen, and how long they last, what people do.

Quitmeyer: Totally.

Levin: Is this where field biologists develop their crafting skills? I mean, like tell us about that.

Quitmeyer: Yeah, that’s one of our goals. So we work of course with a couple of different audiences. So we were actually scheduled to host a bunch of people who maybe more identify as scientists or field biologists; they’re part of a taxonomic organization. And we were going to host them last June to do a workshop on building different sensors. But other times we’ll do workshops with maybe artists, and show them different scientific techniques and stuff that people are currently doing in the field.

But usually what we try to do is always just get a nice mix of people. So, at our house right here…our residency, our lab, our institute for jungle crafts, we have two bedrooms that we normally would host a residence in. But since the pandemic it’s been kind of locked off. But we had people here who were for instance a scientist studying bats, people studying soil microbes. And we had someone who does designs for the reinas in Carnival. So like fashion design kind of stuff, but is also a very avid birder and bird scientist. So we try to mix that up a lot.

And so we do smaller workshops and residencies. We had a whole schedule lined up for both local residents, artists, and scientists from around here in Panama, as well as international residents and scientists. We even had some scholarship money to help them come that we’re just funding from our own freelance work that we’re doing here. But we had to cancel it all last year, and unfortunately Panama’s been under really strict lockdown. Which is good that people are taking it seriously. It’s very unfortunate that the government here is not doing things in smart ways. And so they’re launching kinda discriminatory practices against trans people and having this gender-based lockdown that basically effectively imprisons people who are non-gender-conforming. So that’s really sad.

So everything’s stopped here. But hopefully it’ll start going again, and we can help host people. And then our biggest thing that we run is this thing called The Digital Naturalism Conference. And that’s where we’ll get like a hundred, try to rent out a place for…some semi-remote location—we did one in Thailand, we did one here—for an extended period of time with the goal of just letting people interact with nature. People have all kinds of different backgrounds from that. People were comic book creators…basically everything. The only key thing was you were interested in interacting with nature in some way. So if you go to dinacon.org, you can actually sign up for our mailing list and we’ll send out info in our little mailing list whenever we have the residencies and the conference going again. Hopefully it’ll be soon, and people will all [be] safer around the world.

Levin: Thank you so much, Andy Quitmeyer. It’s been an immense pleasure learning about your work at the Institute for Interactive Jungle Crafts and Digital Naturalism Laboratories. Thank you so much.

And for everyone else, this concludes our transmission for Thursday evening. We begin tomorrow morning at 10:00 AM United States Eastern time with Max Bittker with the Friday morning session of Art && Code: Homemade. Thank you, everyone, and good evening.