It’s an honor to be here, in so many ways, and I want to begin under the title of this talk with three stories that are too big but also not big enough. The Anthropocene, the Capitalocene, and my favorite, the Cthulucene. The Cthonic ones, the not yet finished, ongoing, abyssal, and dreadful ones that are generative and destructive, and make Gaia look like a junior kindergarten daughter.

I’m going to propose to us in the course of the next twenty-five minutes that the Cthulucene might be a way to collect up the questions for naming the epoch, for naming what is happening in the airs, waters, and places, in the rocks, and oceans, and atmospheres. Perhaps needing both the Anthropocene and the Capitalocene, but perhaps offering something else, something just maybe more livable. I’m struck by the fact that two kinds of insights seem to have overtaken the intellectual scholarly world, internationally really, and across the divisions of the disciplines. Simultaneously I propose that it has become literally unthinkable to do good work in any interesting field with the premises of individualism, methodologically individualism, and human exceptionalism. None of the most generative and creative intellectual work being done today any longer spends much time (except as a kind of footnote) talking, doing creative work with the premises of individualism and methodological individualism, and I’ll try to illustrate that a bit, primarily from some of the natural sciences.

Simultaneously, there has been an explosion within the biologies of multispecies becoming-with, of an understanding that to be a one at all, you must be a many and it’s not a metaphor. That it’s about the tissues of being anything at all. And that those who are have been in relationality all the way down. There is no place that the layers of the onion come to rest on some kind of foundation.

How is it, if these are truly the intellectual revolutions and I believe cultural revolutions that are infusing this planet at this time, how is it that the name of our epoch that is seriously proposed and being studied in the international geophysical union and elsewhere, with a report to be issued in 2016, that the name proposed for our epoch is the Anthropocene, with the figure of the Anthropos? What an extraordinary kind of contradiction is implied in naming th epoch that way. But it of course is named that way because of the correct understanding that people, forget the Anthropos, people have been doing on this planet has in fact changed the planet forever, and for everyone. Anthropogenic processes are what give warrant to that name. I will try both to justify and trouble that in the next few minutes.

Jim Clifford last night read a little quote from Always Coming Home that I think has got to stand along with Virginia Woolf’s epigraph from Three Guineas. Actually, it’s not the epigraph of Three Guineas but in the midst of the three guineas Virginia Woolf insists, “Think we must.” Think we must. If ever there has been a time for the need seriously to think, it is now, and it has got to be the kind of thinking that Hannah Arendt accused [Adolph] Eichmann of being incapable of. (That was not an English sentence, but it’s okay, I’m talking about Germans.) Namely, the banality of evil in the figure of Eichmann was condensed in Hannah Arendt’s analysis into the incapacity to think the world that is actually being lived. The inability to confront the consequences of the worlding that one is in fact engaged in, and the limiting and thinking to functionality. The limiting of thinking to business as usual. Being smart, perhaps, being efficient, perhaps, but that Eichmann was incapable of thinking, and in that consisted the banality and ordinariness of evil. And I think among us, the question of whether we are Eichmanns is a very serious one.

Perhaps the utopist should heed this unsettling news at last. Perhaps the utopist would do well to lose the plan, throw away the map, get off the motorcycle, put on a very strange-looking hat, bark sharply three times, and trot off looking thin, yellow, and dingy across the desert and up into the digger pines.

Ursula K. Le Guin, “A Non-Euclidean View of California as a Cold Place to Be”

I’m giving this talk under a particular gorgeous image of Octopus cyanea, or the day octopus, who you can see in the current “Tentacles” exhibit at the Monterey Bay Aquarium. As I have been for a long time, I’ve been trying to stay with the trouble under the sign of science of SF, of string figures, science fact, science fiction, speculative fabulation, speculative feminism, so far. The sky has not fallen, not yet. And I have been inspired by the thinking of Marilyn Strathern and others, who tell me that it matters what stories tell stories, it matters what thoughts think thoughts, it matters what worlds world worlds. That we need to take seriously the acquisition of that kind of skill, emotional, intellectual, material skill, to destabilize our own stories, to retell them with other stories, and vice versa. A kind of serious denormalization of that which is normally held still, in order to do that which one thinks one is doing. It matters to destabilize worlds of thinking with other worlds of thinking. It matters to be less parochial. If ever there was a time, it is surely now, and I think all of us lack many of the skills.

As you know, Ursula Le Guin is my principal inspiration for a great deal, not least her way of approaching questions of narration, evolution, writing, “The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction.” That rather than a heroic story told yet one more time with the first beautiful words and weapons, or words as weapons and weapons as words, instead rethink the questions of evolution in a much smaller vein, with the tiny, hollowed-out negative spaces, the shell which can hold some water that can be shared, the net bag that can carry food back to the camp, that can carry the baby. The kind of sociality that comes from communities making their lives together. Not any kind of Utopia, certainly not absent conflict, but it is not the heroic story of the privileged signifier moving across matrix space to bring back the prize at the end and die.

<img src=“http://opentranscripts.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/06/vlc-00_07_46-2015–06-15–23h43m35s304.png” alt=“Hand-drawn map of the lanscape of Always Coming Home” width=“1280” height=“720” class=“aligncenter size-full wp-image-1245” />Always Coming Home is a story that activates that particular theory of being, theory of evolution, really. The Anthropocene is that name that was proposed in about 2000. The word was invented, actually, by a man who is a great lover and studier of diatoms in the Great Lakes of North America. It’s important to remember that Eugene Stoermer is a freshwater biologist and a lover of the diatoms. His term the Anthropocene was in fact invented in order to signal the Anthropogenic processes that are acidifying the waters and changing the nature of life on Earth. But it was picked up and popularized by Paul Crutzen, an atmospheric chemist who won a Nobel Prize. Paul Crutzen and Eugene Stoermer joined together to popularize the name Anthropocene specifically in relationship to those sorts of processes emanating particularly from the mid-18th century and the steam engine and the extraordinarily expanding use of fossil fuels that acidify the oceans, bleach the corals (They were particularly worried about a vibrio infection in coral reefs that’s responsible for bleaching— We’ll be hearing more about vibrio bacteria both from me and from Margaret [McFall-Ngai] in a few minutes. Vibrio is responsible for cholera, another variant of it. Vibrios are geniuses at communication. They are signallers, queuers par excellence. Those are guys who really get into the world and change it. In the case of the Hawaiian bobtail squid, we can cheer for them. In the case of the bleached coral and cholera in Haiti, I think we have quite another attitude toward the encouragement of vibrio on this planet.

I think the proper icon for the Anthropocene, I think of that human being that is signalled by the Anthropocene, this Anthropos, the one who looks up, is Fossil-Making Man, burning fossils as fast as possible. And what else would signal this man but the Burning Man festival in the deserts of Nevada?

This is of course the burning effigy at one of the Burning Man festivals. They started on the beach, Baker Beach in San Francisco in a much smaller way. Rather small wooden effigies of a man (and a dog, I might point out) that were burned as part of the celebration of the summer solstice, and they grew in the way of Fossil-Making Man’s attitudes toward things, from a rather modest effigy to a 104 foot-tall burning thing in the desert, such that everybody who takes a snapshot of burning man has to sign a contract that the copyright is owned by the Burning Man organization.

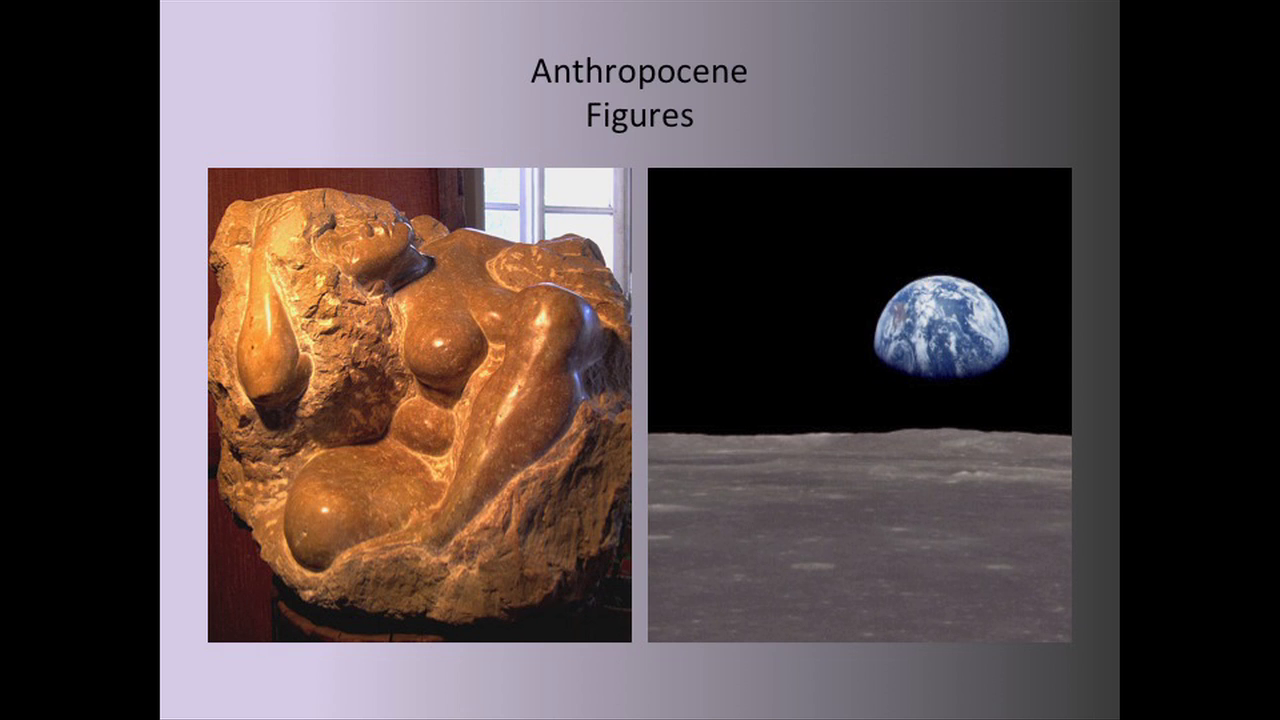

The Anthropocene is also tightly tied to a goddess figure, Gaia, the figure of the Earth who is Gaia partly because Gaia was invoked by James Lovelock to signal what a living planet looks like from space. Very much part of the NASA project, the Apollo missions, the search for life on Mars. Gaia is a figure who emerges into the consciousness of the Anthropos from space. She is an earthly figure, not a female figure but an it, one who figures the metabolism of a planet, that a planet is a whole, autopoietic system.

[This photo] is from one of the Apollo missions, the photograph of the Earth rising from the Moon. That is the perspective from which Gaia is the figure of the Anthropocene.

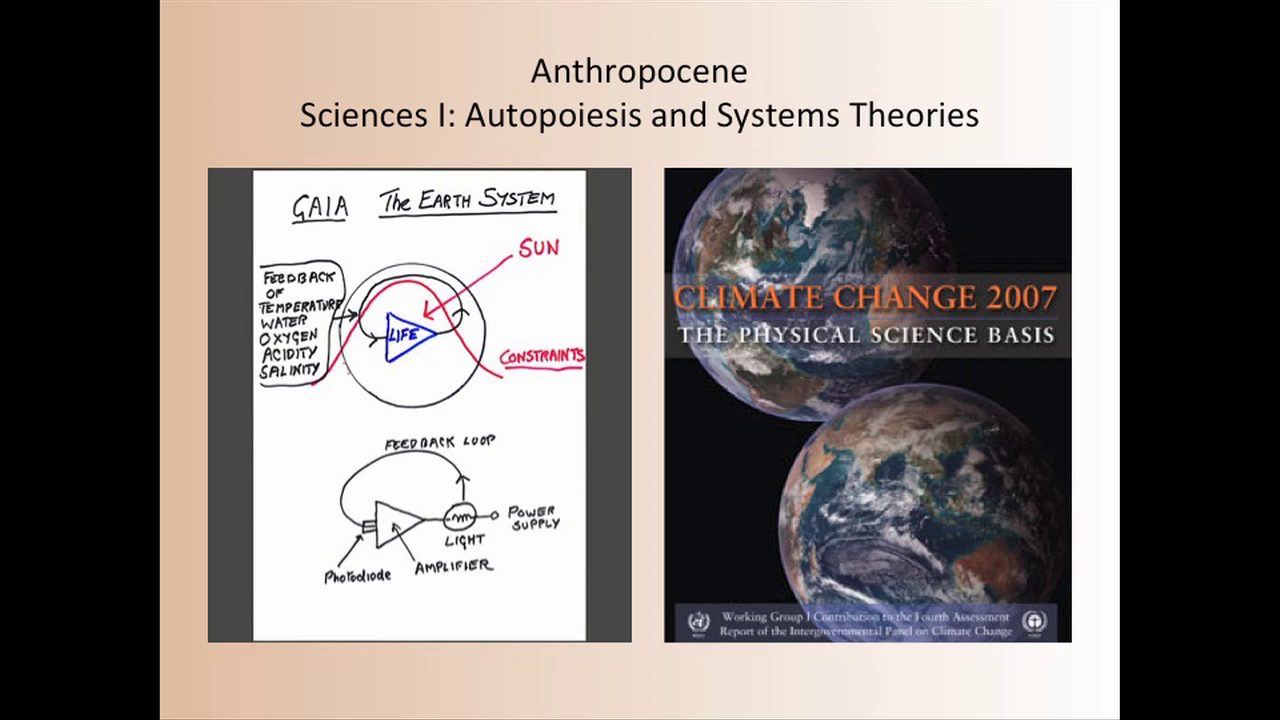

[This] diagram is one that James Lovelock used in one of his lectures on Gaia that gives us a sense of what an autopoietic system looks like. It’s a systems theory. It definitely has to do with complex system processes. It is not a theory of additive change but of system change. It is about self-making and layers of self-making. It’s about order out of disorder. It’s about homeostatic mechanisms in autopoietic systems. The limits of homeostatic mechanisms. The moments of flip from accommodation, accommodation, accommodation, whoops, collapse. accommodation, Accommodation, accommodation, whoops, collapse. Autopoietic theories accommodate collapse as they accommodate adjustment in their systemic ways of thinking. These are the fundamental kinds of logical apparatuses that have been used in scientizing the Anthropocene in its major research organizations and policy bodies, most certainly including the IPCC, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. IPCC has been issuing its reports now for a number of years. It uses the photographs, the snapshots from the cellphone, of the planet Earth, and it engages that kind of system thinking that produces a very particular kind of scale called “global.”

In Anna Tsing’s Friction she does a very interesting ethnographic study of what produces the scale called global, and how the models work, how the institutions work, how it is that something as big as something called “global” emerges as a work object. Anna is not a trasher, Anna is not the sort of thing that says, “Oops, gotcha. Done with that.” but rather, “Oh, that’s how it works. How can this both work and not work for anything that needs to be done on this Earth?” So I am not arguing that we don’t need the kinds of operations that go on under the sign of the Anthropocene, Gaia, autopoietic thinking, and global scale, but I am signalling their very historical and material specificity, and their limitations both mythological and otherwise.

I would also argue (and this is much more tenuous) that the Anthropocene main biological sciences are those of the so-called modern synthesis that was put together crudely from the 30s to the 50s, and then again from the 50s to the 70s, and at some very deep sense these sciences are grossly inadequate to the kind of thinking required for our urgent times. They are powerful. I’m not talking about trashing them. Again I’m talking about understanding what they did, can do, can’t do, and what they stopped. So that the sciences of the modern synthesis work with genes, cells, organisms, populations, species, put them into relationships with each other that were well-described by the mathematics of competition, the competition equations derived ultimately from the thermodynamics of Gibbs, and that the world is profoundly mathematized in terms of those sorts of units that can successfully leave copies of each other in competition with other copying units. Powerful apparatus for understanding the biologies.

But what the sciences of the modern synthesis could not do and did not do was have any grip on microbiology, partly because microbiology works in such a weird way. The little critters just do things we would not permit in the average middle school. They could not and did not deal with symbiosis. The many biological process that have come to be shown as general to life on Earth were ungraspable within the sciences of the modern synthesis, basically. They were really minority sciences. Everything to do with lichens and coral reefs that became so exciting in the late 19th century in some significant way disappeared from the leading sciences until very recently. And they could not and did not deal with developmental phenomena. They could not deal with change through time in any very serious way.

I would like to propose for perfectly obvious reasons that for all of the failings of the Anthropos and the Anthropocene, and all of the strengths of both, the Anthropos did not do this thing that threatens mass extinction, and that if we were to use only one word for the processes that we’re talking about, it should be the Capitalocene.

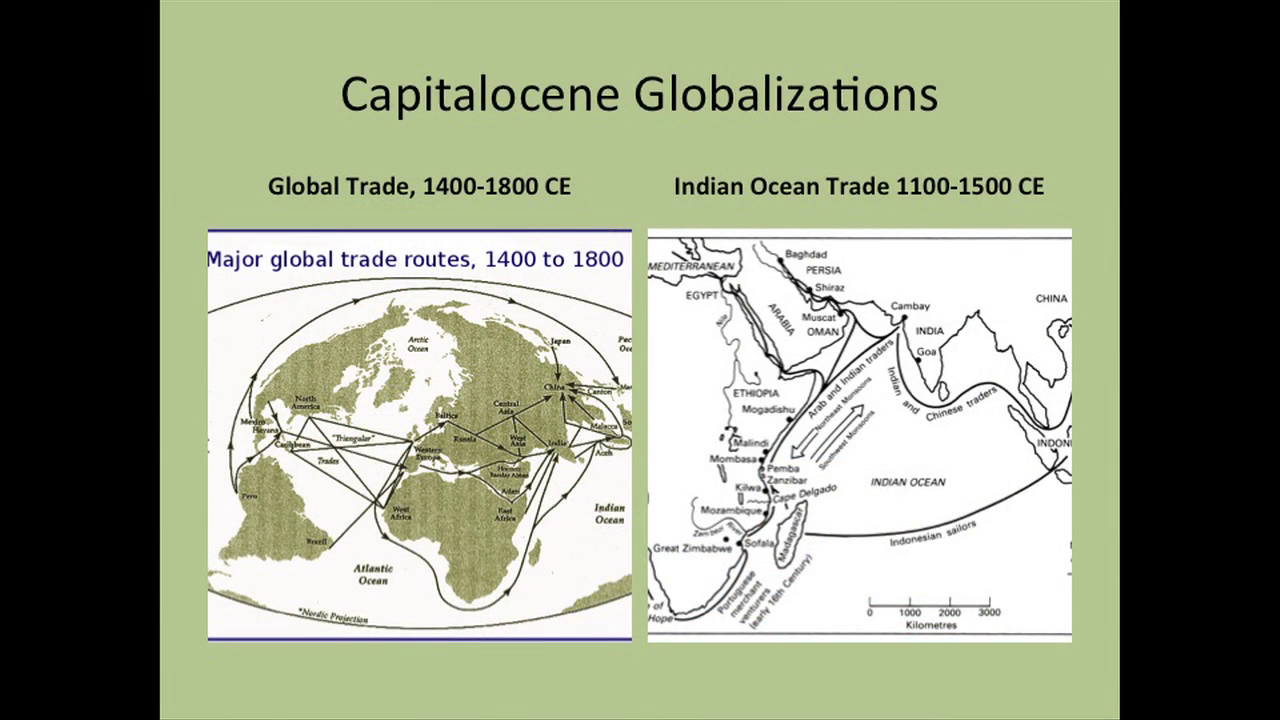

Furthermore, those processes that are signalled by the extraordinary primitive accumulations and extractions of organizations of labor and productions of technologies of very particular kinds for the extraction and maldistribution of profit, so on and so forth, did not start in the mid-18th century, nor do we need to go back to “deep time” and the end of the last Ice Age and play the notion that human versus nature is as old as our species itself. Stark nonsense. But we do need to go deeper in time than the mid-18th century, and I use this slide simply to signal the formations of markets and accumulations of wealth in the great trade routes, many of which figured China as a major player, and the Indian Ocean as a major player. I do this simply to signal that those metabolisms of the oikos and [ikos?], of economy and ecology, and of worlding, and of trading and making, need to be figured older than the mid-18th century, and that does not mean going back to some kind of deep ecology.

Clearly, the melting of the ice around the Arctic is very important to the Capitalocene, in no small part because something like 30% of the natural gas reserves are in the Arctic seas under the ice, or the no-longer ice. I give you here an old ship that didn’t quite make it, and a new ship which is quite capable, thank you.

And then I give you the third age of carbon, which I believe we are living in. I’m indebted to Michael Klare for this. That is to say that even though sustainable technologies of all kinds are getting vast investments, way more money is going into sucking the last calorie of fossil fuel out of the tissues of the Earth and the melting of the ice in the Northwest Passage. The melting of ice in the Hudson Bay is a big part of this.

What we have here is Greenpeace going against a Russian oil rig in the Russian areas of the Arctic. The international competition in the Northern seas is astonishing. The military competition, the corporate competition. The sucking of the last calorie of carbon out of this planet is a big deal.

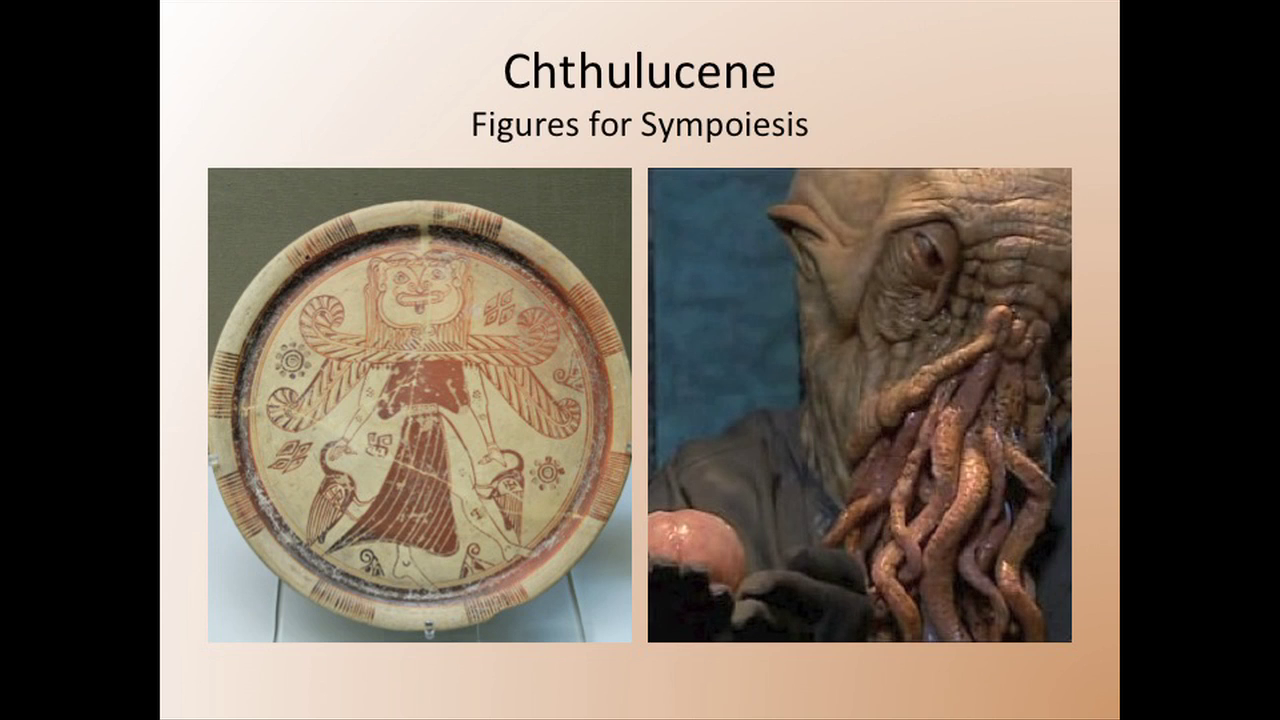

So we get to the Cthulucene. My figure [on the left] is Potnia Theron, or Medusa. Medusa is the Greek version of this snake-haired cthonic entity who is Potnia Theron, Potnia Melissa the goddess of the bees, who is a very old and cthonic figure who is in no one’s pocket. A figure of creation and destruction, an entity of extraordinary powers, and I would suggest to you that those who think the cthonic ones are old, traditional, done, been there, supplanted by civilization, are simply wrong. I figure that for this purpose with the Ood out of Doctor Who science fiction film TV series that I bet everybody in the room has at least seen some of. And I remind you that the tentacular ones, whose faces are tentacles and not eyes, whose face are feelers, that the Ood had their hindbrain outside their body and that the bad enslavers came and cut their hindbrain, which was the part of them that tied them to each other and to the possibility of what they call a hive-mind but let’s just call it community or thinking with each other, and replaced it with a little glowing globe that could be controlled by the slavemakers. So I think of the Ood as a perfectly appropriate Cthonic One for the Cthulucene.

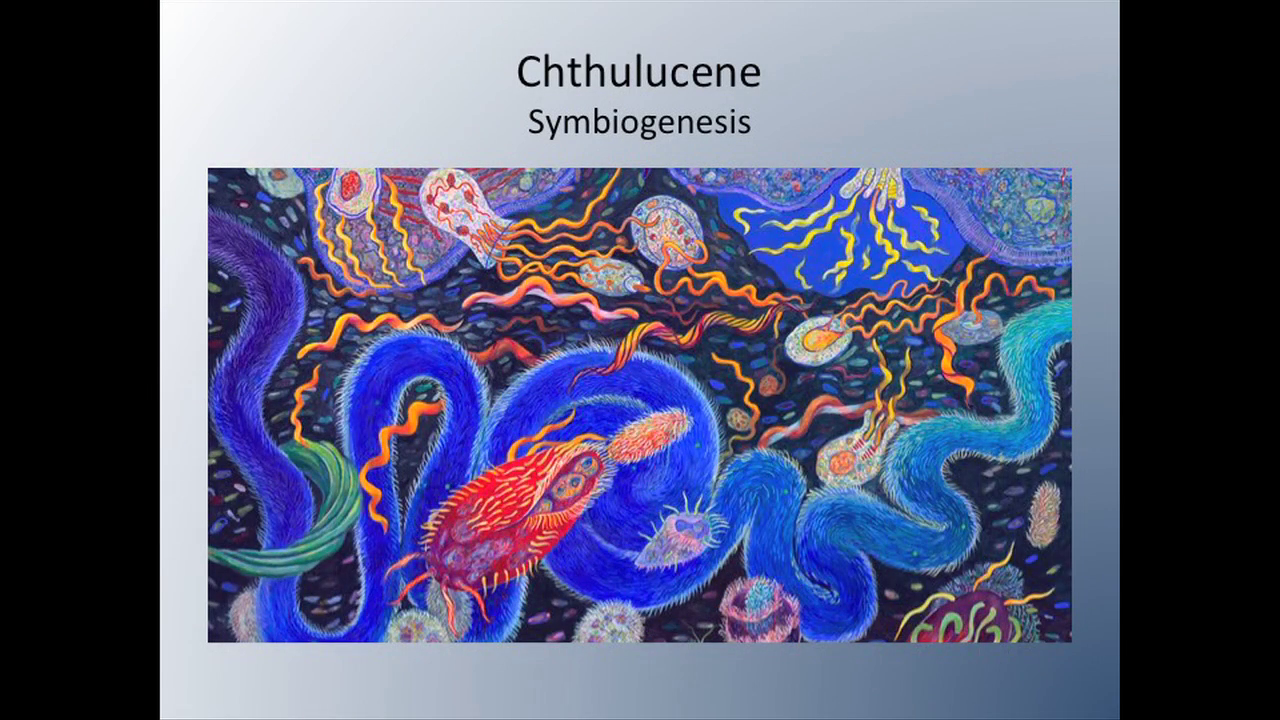

Shoshanah Dubiner, “Endosymbiosis: Homage to Lynn Margulis”

But let’s move to the biologies and go to Lynn Margulis. This is “Endosymbiosis: Homage to Lynn Margulis,” a giant painting of several feet by several feet, on the wall between the biological sciences and the geosciences at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where Lynn proposed, and she and her labs showed, that the origin of complex cellularity on this Earth is an endosymbiotic event. That is, some bacterial sorts of critters ate others and got indigestion and stuck around with each other. That the origin of complex cellularity is an act of indigestion. This painting is of the critters involved in indigestion that is perhaps the world’s first complex worlding, except Lynn would disagree with that since she was quite sure the bacteria were already quite complex enough, thank you.

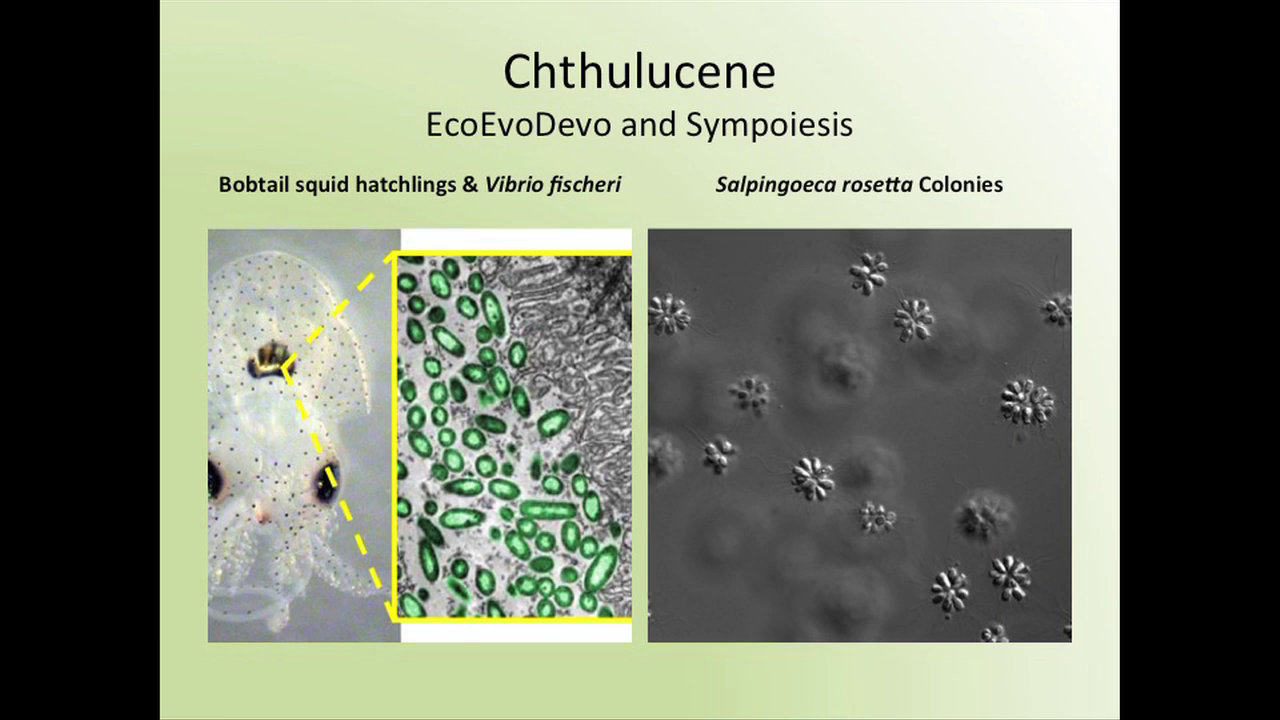

You’ll hear more about this from Margaret, but it’s not just multicellularity which is at a symbiogenetic event of cthonic proportions, but also if you take this lovely little Hawaiian bobtail squid, get it hatched and fill a little specialized pouch with very particular bacteria at a very particular time, those very particular bacteria will signal metamorphic changes in the squid that allows it to build a certain kind of structure that’s really crucial for its being able to harbor light-emitting bacteria as an adult and look like a starry sky from below so that it can swim along and get its prey. It’ll glue sand to its back so from above it looks like a sandy bottom and from below it looks like a starry sky, and it can shoot its way through the waters gobbling up dinner because of symbiogenetic events. So that’s about developmental programming. It’s about, to develop properly through time, we need each other in an obligate symbiosis, and this proves to be way more general than one would think.

The other slide is a similar kind of argument out of Nicole King’s laboratory at Berkeley, which is about the origin of animal multicellularity from the clumping of choanaflagellates in the presence of certain kinds of bacterial infection. Infection is necessary to complexity.

We are all lichens now. We have never been individuals. From anatomical, physiological, evolutionary, developmental, philosophic, economic, I don’t care what perspective, we are all lichens now.

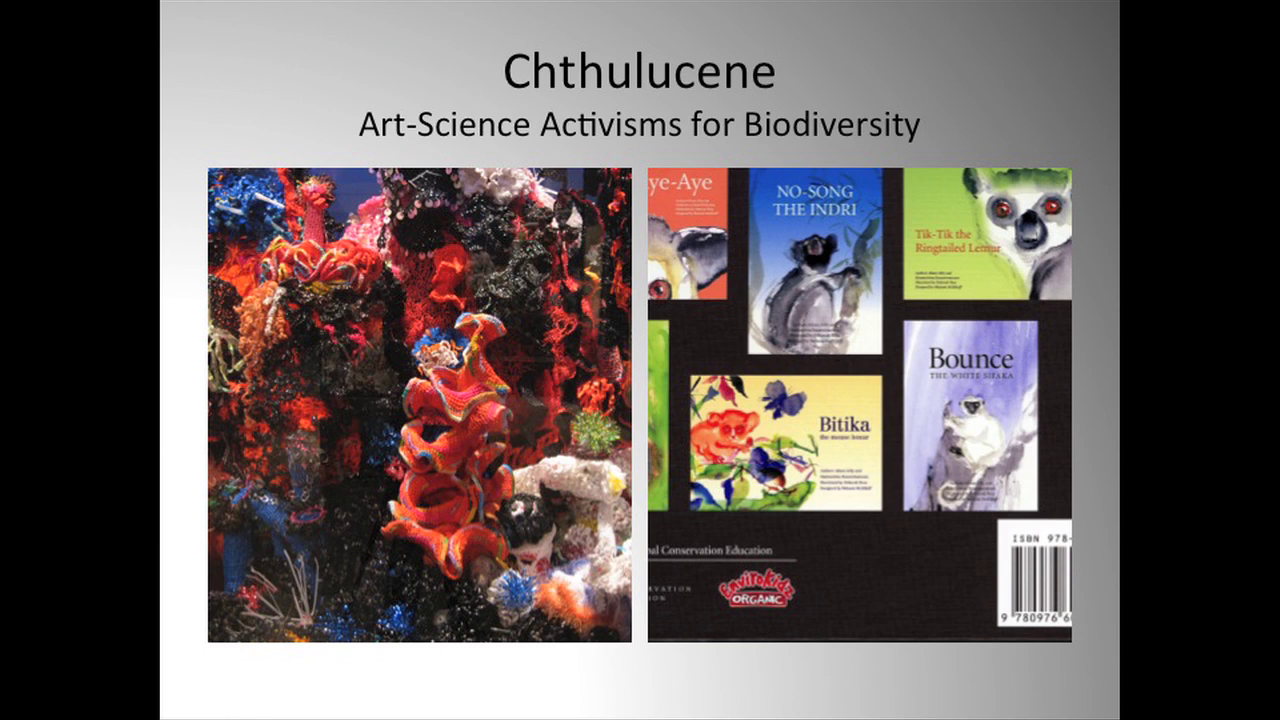

Art-science activisms inspire me at a level— and I refuse to give any of my presentations without a kind of potent alliance with those who are working with beauty and fury in their enlisting the possibility of ongoingness. The first picture that you see up there is from Margaret and Christine Wertheim’s Institute for Figuring. The hyperbolic Crochet Coral Reef, where the practices of women’s crocheting the non-Euclidian figures became very important mathematical figures. Something like 27 countries and more than 7,000 people have been involved in the collaborations to make displays of coral reefs from crocheting. They’d enact a solidarity with the reefs through women’s fiber arts, environmentalism, the mathematics of complex non-Euclidian spaces, the international collaborations of installation art. They are an extraordinarily interesting activation. This is the “Toxic Reef,” made significantly out of discarded reel-to-reel tape and other toxic fibers.

The other is a book project put together by a friend of mine who died a couple of months ago, Alison Jolly, a primatologist who studies lemurs in Madagascar and was deeply involved in conservation. Alison was horrified by the fact that Malagasy children study European animals and have no literature or animal fables in the Malagasy language, or pictures of Malagasy animals, the Madagascar flora and fauna. She and her colleagues have produced an astonishing series of about ten children’s books that are bilingual in Malagasy and English. Real natural history. These are exciting animal stories, fabulous animal stories, that are an effort to inculcate in the young a love of place, a love of home.

Cthulucene reworlding. Compost not Posthuman. “Revolution is but thought carried into action,” Emma Goldman. The activation of the cthonic powers that is within our grasp as we collect up the trash of the Anthropocene and the exterminism of the Capitalocene, to something that might possibly have a chance of ongoing.

Thank you.

Further Reference

Citations

- Theatre and the Threshold of Death: Lectures on the Dying Arts

- Embracing a Sankofic Approach to Enduring Political Crisis

- La mediazione dell’arte pubblica come processo di ricerca geoestetica

- Gestische Forschung: Praktiken und Perspektiven, “Wenn die Situation zustimmt”

- Bildbetrachtung als Synthese von Umwelt und Bewusstsein

- Coral Whisperers: Scientists on the Brink

- Grounding God: Religious Responses to the Anthropocene

- Environment-making, cheap-nature, and care : an anthropological study of the Hazel Food, arts, and crafts market in Tshwane

- Haraway’in Simpoiesis Kavramı ve Birlikte-Düşünme Pratikleri

- Becoming octopus: Indigenous ways of knowing and green leadership

- La fotografía de paisaje en el Antropoceno: en busca de nuevos horizontes

- Walking journeys into everyday climatic-affective atmospheres: The emotional labour of balancing grief and hope

- Myth and Environmentalism: Arts of Resilience for a Damaged Planet

- Putting the trans* into design for transition: reflections on gender, technology and natureculture

- Handbook of Research on the Relationship Between Autobiographical Memory and Photography, “Photographic Non-Self”

- Affect in Organization and Management, “Corporeal Ethics in the More-Than-Human World”

- Geo-Spatiality in Asian and Oceanic Literature and Culture: Worlding Asia in the Anthropocene, “Agrarian Witnessing and Worlding for the Anthropocene”

- Precarious Feminine Identities

- Evolution, Revolution and the New Man: An Ethnographic Investigation into Microchipping, Human Augmentation and Building New Futures

- Through the Looking Glass: An Environmentally Conscious Economy in New From Nowhere

- Transitioning to a circular economy, “An Introduction to the Circular Economy”

- La ficción climática, narrativa del antropoceno

- “Pattern Discognition,” Christina McPhee: A Commonplace Book

- Agrarian Witnessing and Worlding for the Anthropocene

- The spectacle of ‘tantruming toddler’: Reconfiguring child/hood(s) of the Capitalocene

- “Obligate Storytelling,” Ecology Without Culture: Aesthetics for a Toxic World

- Risks and the Anthropocene: Alternative Views on the Environmental Emergency, “The International World of Disasters: Beyond Reflexivity, Surpassing Naturalism?”

- Space Matters: Barriers and Enablers for Embedding Urban Circularity Practices in the Brussels Capital Region

- Children and the Power of Stories: Posthuman and Autoethnographic Perspectives in Early Childhood Education, “An Ethics of Flourishing: Storying Our Way Around the Power/Potential Nexus in Early Childhood Education and Care”

- Eating a nuclear disaster: A vital institutional ethnography of everyday eating in the aftermath of Tokyo Electric Power Company’s Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant disaster

- Ruskin and Lichen

- MRX Maschine

- Art, EcoJustice, and Education: Intersecting Theories and Practices

- The Bloomsbury Handbook of 21st-Century Feminist Theory

- Ethics and Politics of Space for the Anthropocene

- Opposing Colonialism, Antisemitism, and Turbo-Nationalism: Rethinking the Past for New Conviviality

- Le devenir-œuvre d’art : une analyse processuelle d’une expérience curatoriale en arts médiatiques

- Unsettling the Anthropocene: Experiments in dwelling on unstable ground

- Going dark : care-full castings and delight-full deviations for a networked fiction in an everyday world

- Building Ecological Ontologies: EcoJustice Education Becoming with(in) Art-Science Activism

- Temporality, technology and justice in Hannah Arendt: A critical approach

- Climate Realism: The Aesthetics of Weather and Atmosphere in the Anthropocene

- Walking an Article Into Being Becoming Together

- Skandinavisk sci-fi-poesi

- O Balançar do Manto

- Career Paths in Human-animal Interaction for Social and Behavioral Scientists

- Critical environmental law as method in the Anthropocene

- Expanded Choreography: Shifting the agency of movement in The Artificial Nature Project and 69 positions

- An Active Student Participation Companion

- Edible Subjectivities: Meat in Science Fiction

- The Stories We Tell –The Stories We Need to Tell. How Can Storytelling Effect Social Change? The Case of Wu Ming

- Covid-19: When Species and Data Meet

- Selvagem: sujeito e território, exclusão e resistência

- Spells of our inhabiting: transitioning from the spectre of Gnostic estrangement to a philosophy of entangled overflowing

- Transdisciplinary Journeys in the Anthropocene: More-than-human encounters

- New Dark Age: Technology, Knowledge and the End of the Future

- Decolonizing Extinction: The Work of Care in Orangutan Rehabilitation

- The Anthropocene: Animals and the Covid-19 Pandemic

- La representación de los espacios de vida de la mujer en el ciberfeminismo

- Tecnociencia, Feminismos y Biopolítica Táctica. Contextos y prácticas del colectivo subrosa.

- 25 years of staying with the trouble — or why won’t the professor tell me how to save the world?

- A Crystalline Quilt for the Thick Present

- Public protest, public pedagogy and the publicness of the public university

- When ‘Angelino’ squirrels don’t eat nuts: A feminist posthumanist politics of consumption across southern California

- Architectural history in the Anthropocene: towards methodology

- Taming the climate? Corpus analysis of politicians’ speech on climate change

- The anthropology of wearables: The self, the social, and the autobiographical

- Wave form, wave function

- Making love on the River Anthropocene: Resisting the neoliberalization of water and nature

- How do politicians understand and respond to climate change?

- Expanding Radio: Ecological Thinking and Trans-scalar Encounters in Contemporary Radio Art Practice

- Reflections on the Arts, Environment, and Culture After Ten Years of The Goose

- Matter and Mind: on embodied ethics, education, and the environmental imaginary

- Living with worms: On the earthly togetherness of eating

- Becoming With: Writing Ourselves in the Chthulucene

- Politics of Ecological Nostalgia

- Unsettling antibiosis: how might interdisciplinary researchers generate a feeling for the microbiome and to what effect?

- Congocene : the anthropocene through Congolese cinema

- Encounters with materials in early childhood education

- Research Methods in Environmental Law, “Critical environmental law as method in the Anthropocene”

- End! angered Species Plantation Memories and Other Troubled Voices in the Age of the Capitalocene

- Das Szenarium, in dem sich Medienanthropologie und Neue Materialismen treffen

- Arte transviada de código aberto

- Cartografías ecosóficas y situadas. Hacia una justicia zoecentrada y feminista

- Jelen korunk komplex környezeti és gazdasági kihívásai~ pálmaolaj esettanulmány tükrében

- Future child: Pedagogy and the post-anthropocene

- Actors and Accidents in South African Electronic Music: An Essay on Multiple Ontologies

- Black Sky Thinking

- Asymmetric Labors, “Matters of Life and Death”

- CompuQueer: Protocological constraints, algorithmic streamlining, and the search for queer methods online

- Living ethics in a more-than-human world, “Towards living ethics”

- Listening beyond Radio, Listening beyond History. (A proposal for alternative radio histories)