John Palfrey: I want to just note one thing, that as I’ve listened over the course today I think we should keep challenging ourselves on, is this question of whether or not this really is an issue where the left or the right is more or less likely to be purveyors of truthiness. Or whether the sort of open net, in a sense—on the substance in fact favors in the SOPA example or others that Yochai used—favors a certain kind of truth or the process of letting truth spread.

I suspect we are more in this room… Well, I should say we’re probably not by and large devotees of Fox News, just listening to the commentary. And I guess I resist a little bit this impulse that this is, you know, the left is always right or correct, and that the right is always purveying misinformation. That may not be right, but I do want to just note that I think we should keep challenging ourselves in that way. The openness of the net itself as an example, in the SOPA case seems, to be one where there actually might be some favoring of certain kinds of cultures and technologies and topics, where the spread of the kind of thing that Yochai laid out might actually have somewhat more grip than that left/right thing. Anyway, I throw that out as just an observation as we switch over to Christian and Eszter. Thank you.

Christian Sandvig: Thanks so much, John. Okay, while I get set up welcome to Interventions for Individuals: Tools and Personal Empowerment. I’m Christian Sandvig. Like the sessions in the morning, we’re moving to a format now where we’re gonna do some rapid-fire presentations, so I appreciate your patience with our brevity.

I have two big points for you, and then Eszter, my co-moderator, will say her points to frame the panel, and then we’ll introduce the people on the panel in the order indicated in the program.

So my two big points are these. I’d first like to tell you a way to think about interventions for individuals that I think might be useful. And then second I’d like to throw down a research and tool-building challenge.

So for the first point, how many people have ever run across this book? Anyone? It’s obscure and old. Right, so it’s Mark Stefik’s book way back in 1996. Did they even have the Internet in 1996? That’s so long ago. But he said in 1996 that actually there are four ways to think about the Internet that he called “archetypal metaphors.” And his point was that the Internet is a really complicated technology and it can be used for many different things. But that the metaphor that we have underlying our thoughts about the Internet is really going to condition what public policy or regulation seems useful, what design interventions seem useful, and so on.

So his four ideas about the Internet is that we think about Internet, number one as a library. And this was the 90s and we had this electronic library, the digital library. That doesn’t mean that we digitized libraries, it means that that’s the metaphor we used to think about the Internet, as a place that has information that we can look up. His second was we think of it as the mail. Or you could say the telephone. And so that’s more about individuals and interpersonally communicating in some way. The third is that we think of it as a virtual world. And the fourth is that we think of it as a marketplace.

Now, I find these really valuable in thinking about this conference as it’s unfolded so far today. I think the dominant metaphor in this room so far has been the Internet as a library. The library’s where you go to look at newspapers in the reading room, right, and it’s where you go to look up facts. But you know, obviously that metaphor doesn’t really work with the Internet. The library is publicly funded. And the library has these trusted intermediaries called librarians, right, and the Internet doesn’t have that. It has this other class of intermediaries.

So the way that I think about the presentations that we’re going to see about interventions for individuals are really that we have kind of two areas of work that I’ve seen a lot on. One is a kind of “help the patron of the library” metaphor. Or “empower the individual.” Or you could say “blame the patron.” So in other words the library doesn’t produce the information that you want, and the solution should be that we should get the patron up to speed. But you don’t know how to use the card catalog properly. If we can just help you out, then we’ll help solve this problem about information.

What I’d like to do is also draw attention to I think what was Yochai’s challenge in the morning. And that was to move away from this library metaphor to say that what might be happening is that on the Internet we actually have a metaphor of the library, but what’s actually happening is a marketplace. So you think of it as a library where you’re looking things up, but Facebook thinks of it as a marketplace where it’s selling you, or Google thinks of it as a marketplace.

And so a second class of tool that I haven’t seen as much work on but that would be great to do would be a class of tool that tries to point out to the user that they are in fact in a marketplace when they think they’re in a library. And that could involve the political economy of the Internet. It could involve money flows. We’ve heard something about that.

But then I’d like to depart from these two areas in which I think we’ve done a lot of work and issue a kind of research challenge where I don’t think there’s been a lot of work, although the panelists that’re coming up may prove me wrong.

I want to move to my second big point and talk about Robert Merton. This is not Robert Merton. This is not Robert Merton. Anyone who this is? Kate Smith! Alright, Kathleen Hall Jamieson nails it. Yes.

So Robert Merton, very famous Columbia sociologist. He coined the phrase “role model.” He coined the phrase “self-fulfilling prophecy.” He wrote in 1945 about Kate Smith. And he was afraid. He said you know, Kate Smith is such an amazing media celebrity in this year of 1945. She is so powerful as a media celebrity that it may be that she can get people to believe things that aren’t true, just because she is this really powerful celebrity.

And I imagine, I don’t know that he did, but I imagine maybe in 1945 he had a conference at Columbia that would be just like this one. So it would be like our conference. He didn’t have the gift of naming that the Berkman had. Because he called this idea “pseudo-gemeinschaft.” He did have a gift of naming but just not in this case. And what he meant by that is that in 1945 people were thinking about propaganda, right. It was on the mind. And he said technology is really interesting because what’s happening is that technology is creating this false community of values where people will believe that they are in a community of values with Kate Smith and they’ll believe what she has to tell them about issues of the day, when in fact it’s an instrumental relationship and they shouldn’t believe her. And he was really concerned about this.

He actually said in 1945, though— He had this different take that I haven’t seen at the conference here today. Instead of saying what we need to do is to find the facts that are wrong and combat them, he took it in a very different direction. He said really what we have is a situation where we could create what he called “a climate of reciprocal distrust” when there’s too much emphasis on facts and misinformation. And the danger, he said, is that “society will be experienced as an arena for rival frauds,” and that this is the major challenge that we face. It’s not that there is misinformation and we must respond with fact, but rather that all facts will be devalued.

And he said that what might happen is that we would begin to fetishize sincerity, and the natural, and the spontaneous. And I was really struck by that with Tim’s comments about his botnets that would fake sincerity, you know, by using Mechanical Turk. So his big concern was not that there are facts that are wrong or that people could be persuaded to believe things that weren’t true by say, Kate, but rather that all facts are being devalued.

And so this is my research challenge. I wonder if it’s possible to have a tool that would be empowering for individuals, but that it wouldn’t actually address specific factual problems. Instead it would address this climate of reciprocal distrust, or address the status of all facts and say how do we make society as something that’s not experienced as an arena for rival frauds.

So okay. So that’s my challenge. Hack day, you guys can solve that one for me…he’s not looking. Alright. There’s no hope, then. They’re not going to address it.

Okay. So alright. And now I’m going to hand it over to Eszter, and and she’s going to speak briefly. And then we’ll move on to the rest of the presenters in the schedule.

Eszter Hargittai: Thank you. Okay, so let’s start with a factoid. Where did Stephen Colbert go to school?

Audience member: Northwestern.

Hargittai: Yeah. So, he is a Northwestern University School of Communication alum. Although you might think you he’s a Dartmouth alum. No? God, do you guys actually watch his show?

So the Steven Colbert on The Colbert Report did go to Dartmouth. But the Stephen Colbert in real life went to Northwestern. Anyway. I thought I’d throw that out there as a little thing to start with. We’re very proud of him at Northwestern of course.

So, we’ve gotten all sorts of challenges. Things that we have addressed and things that we haven’t really addressed. And so I’m going to through my part into that mix. Part of the title of our session is “tools” and then part of it is “personal empowerment.” And I think we’ve heard a lot about tools. And we’ve heard a lot about what content is out there and what is the misinformation that gets around, how much of it is around.

What I don’t think we’ve talked about that much is how people actually see the content that’s out there. So, people. What are they actually doing? How do they understand what’s out there, right? So we can come up with all sorts of tools. But if there’s a tool out there and no one uses it, did it make a difference, right? So that’s just another angle to think about all this.

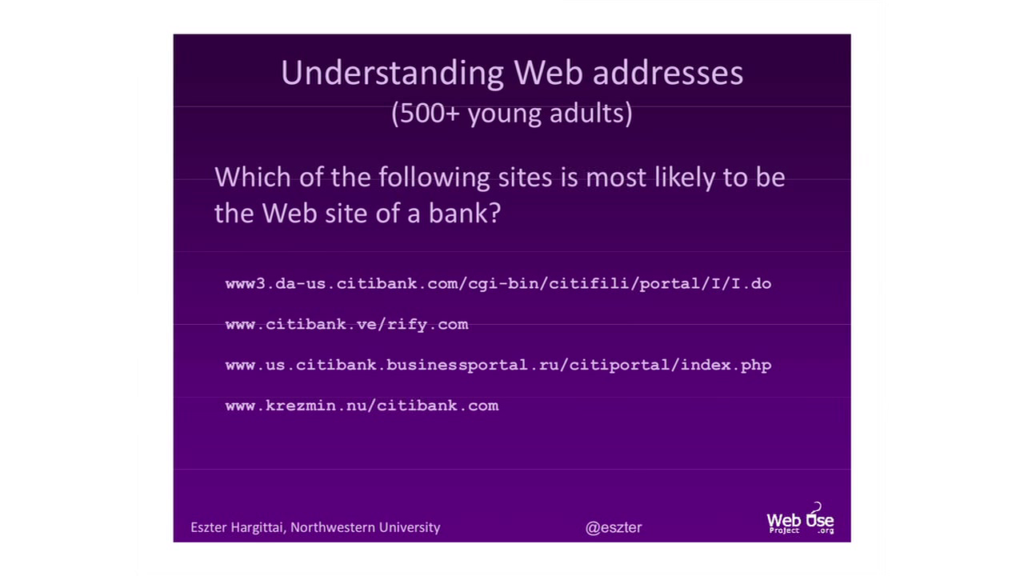

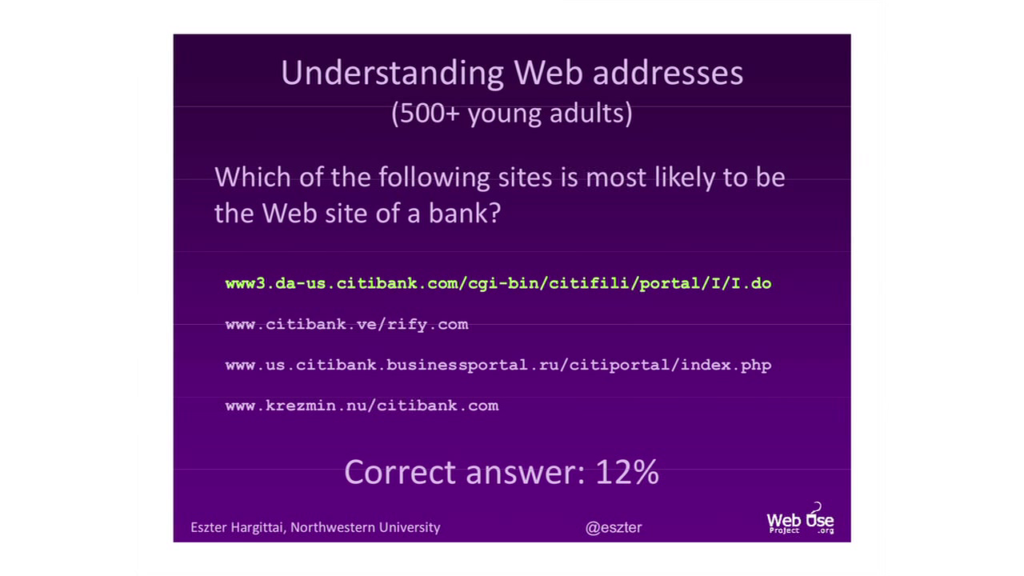

And so I want to share just a tiny bit of my research about how your average person out there actually encounters some information that they see online. So, thanks to support from the MacArthur Foundation I’ve been studying young adults and how they approach the Internet for the last five or so years. And here I just wanted to report on a question that I posed on a survey to some young adults about being able to read URLs correctly, right.

So here’s a multiple choice question and I’ll give you a moment to look through the options. And I have a feeling in this room most of you will probably get this right. Think for yourself what you think you would pick. Well, here’s the one that’s right, and hopefully that’s not too surprising to too many of you.

But what did these young adults, the supposedly digitally savvy net generation pick? Well, they picked all sorts of other things. Just over 10% of them actually got this question right.

So what does this say about our people’s ability to figure out the credibility of content they encounter when they can’t even tell what web site content is hosted on? So that’s the point here.

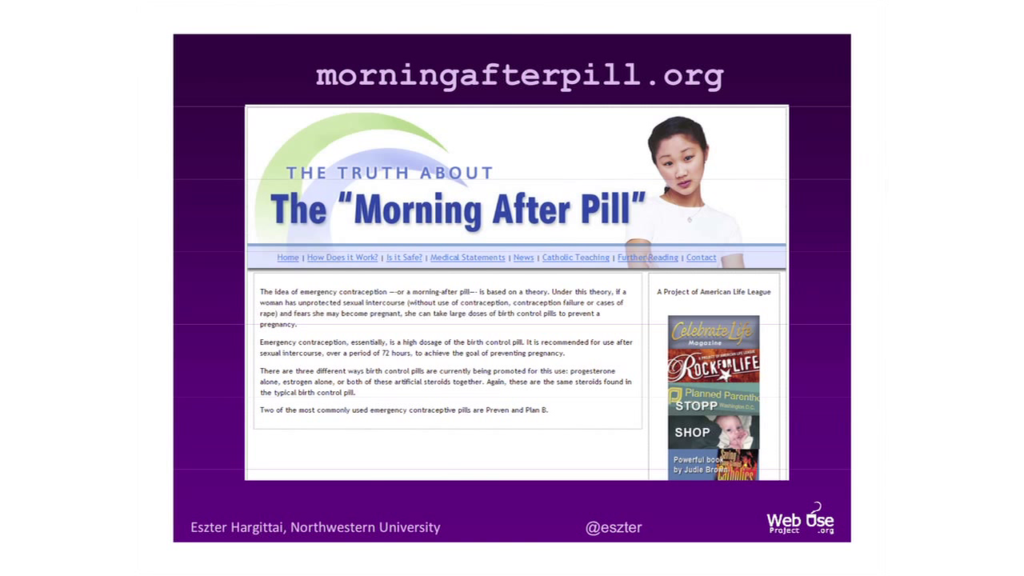

Just wanted to show you just two examples of web sites that I think are interesting little case studies of what you might encounter, depending on what web sites you’re surfing. This particular example I didn’t know about until we were running a study and we asked people to— We gave them a hypothetical about an unfortunate incident with a broken condom and how would they deal with it. And so one of the search terms one might put in in that instance is “morning after pill.” And if you do that search on Google, one of the results you get is morningafterpill.org, which sounds potentially relevant.

So you click on it and if you just sort of go with the flow, you read this site. But eventually if you’re really careful, which most people it turns out are not, it turns out that this is a web site that is very much against the morning after pill and will in no way let you know how you can obtain it.

However, there seems to be a very interesting misconception about the whole idea of .org domain names. For those of you who know how domain names work, .org and .com are pretty much equivalent. You can buy it the same way. There’s really no difference in terms of the credibility of content that might be hosting on a .org or a .com. Interestingly that’s not at all how the average person perceives these sites. .org seems to have much more credibility. So that’s just one example.

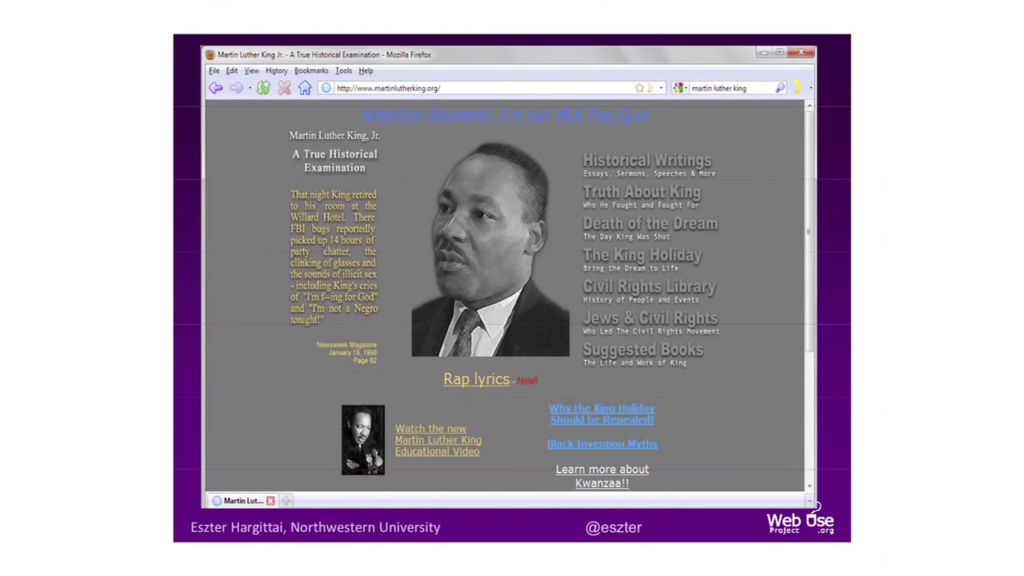

Another one that you may have heard of or may have seen before, and this one came to me— Again, I didn’t know about this web site until a student actually used it for a homework assignment and then I incorporated into a project. This one is if you search for information about Martin Luther King. One of the web sites you gets is martinlutherking.org. Raise your hand if you’ve ever seen that web site. Okay, so some of you know where this is going. By the way, not to be tough on Google. On Bing it comes up pretty much on top as well, or near the top.

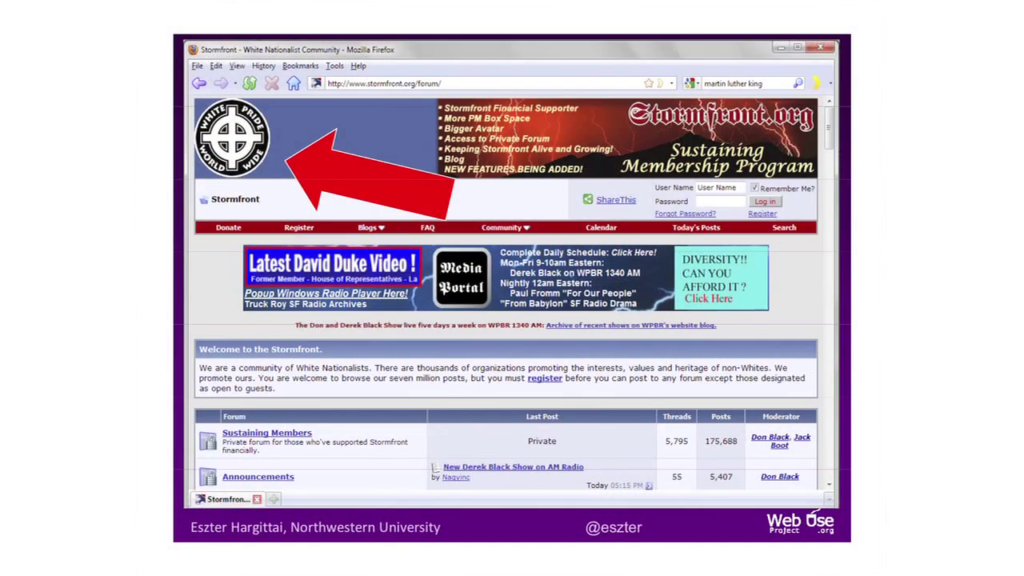

So if you go to martinlutherking.org, this is the web site you get. I’ll give you a moment to look at some of the content. If you’re actually somewhat critical, and if you’re in the context of a truthiness meeting so you know that I must be showing you this for a reason, you might start noticing things that might not really make sense on a web site about Martin Luther King? So if you scroll down, you see a link to Stormfront, which takes you to this web site.

And here you find out who sponsors this web site. And then you might think hmm, that might not be the most credible information for Martin Luther King content.

What we did— So first of all, again because it’s a .org site a lot of people think it is credible. They actually talk about it as a source they would use if for example they were doing a homework assignment.

So one thing we did and this is one of these challenges where I think we need way more work of this sort. Because basically what happens is we create all sorts of tools and on occasion if we’re lucky they’re interventions that people think of, training sessions, but we never evaluate them, right. We don’t know if training sessions we have out there to improve people’s skills actually work.

So I designed a very tiny—I mean these are expensive—a very tiny random assignment training intervention where the idea was to help people learn about this web site and the questionable credibility. And several months later, then observed people who had gotten the training and people who hadn’t, and basically found that of the people who went through the training about URLs and specifically this web site (so it was a very targeted program) almost nobody would have relied on this web site, whereas almost half of the people who didn’t get their training would have relied on this web site.

So there are actually ways of intervening and helping people understand better the content of what’s out there and the credibility of content that they find. But currently we just don’t seem to be doing a lot. So I thought it was interesting when Ethan was talking about the culture of MIT/Harvard, I thought where that was going is that at MIT we have the tools and then Berkman it’s the policies and sort of institutional-level questions.

A little bit missing from this is I think then the people. But what’s great about Berkman is that actually it’s really good about incorporating social science and seeing how people actually use services, and how can we study people on the ground. So we do have that. So my call for where to go with the rest of the conversations is not to forget the people that we’re actually talking about, right, the average users. What do they know? What can they do? And how can we not just create tools but actually make sure that they know about the tools, and know how to understand what’s out there better? So that’s my call for the conference. Thank you.

Further Reference

Truthiness in Digital Media event site