Golan Levin: Good morning. And welcome back everyone to our second session of today. This is Art && Code: Homemade and I’m delighted to welcome you to a presentation by LaJuné McMillian. This is LaJuné’s second Art && Code. LaJuné presented at the 2016 Art && Code called Weird Reality, which was was all about new and independent visions for augmented and virtual realities.

LaJuné is a new media artist, maker, and creative technologist based in Maryland and New York. Their work integrates performance, virtual reality, and physical computing to create intersectional media systems that support the needs of suppressed communities. LaJuné McMillian.

LaJuné McMillian: Thank you! Hi. My name is LaJuné and I’m a new media artist. And yeah, I’ve been doing this work now for about seven years, integrating performance with augmented and virtual reality experiences, as well as installation art. And I started this work as part of my time at NYU Tandon’s Integrated Digital Media program.

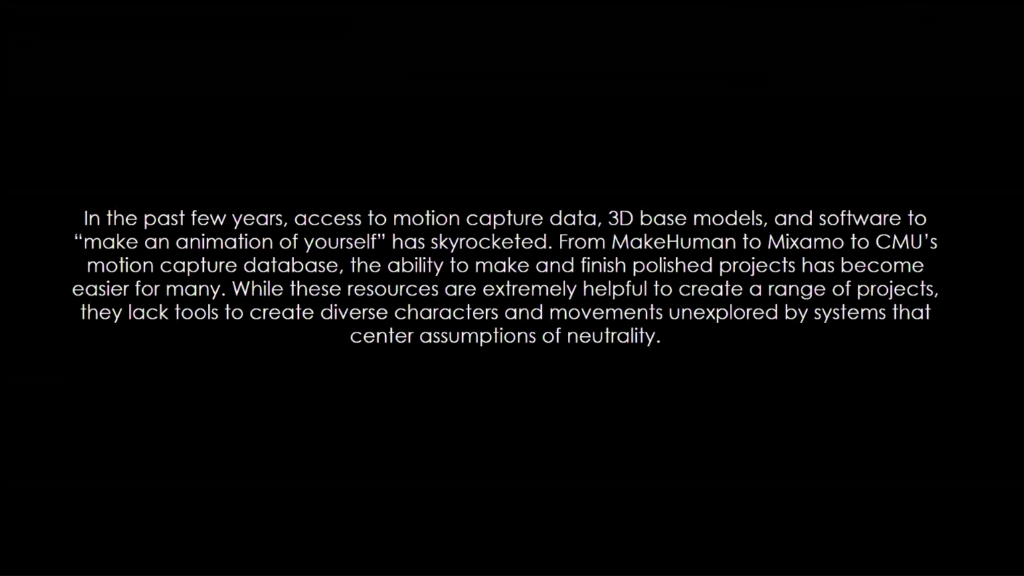

After I left the program I realized that my access to a lot of these technologies was very limited. And it made me question access just in general to all of these different technologies. So yeah, in the past few years access to motion capture data, 3D character based models, and software to “make an animation of yourself” has skyrocketed. From MakeHuman to Mixamo, to Carnegie Mellon’s motion capture database, the ability to make and finish polished projects has become easier for many. And while these resources are extremely helpful to create a range of projects, they lack tools to create diverse characters and movements unexplored by systems that center assumptions of neutrality.

And so I decided to start the Black Movement Library, which started as an online database of Black motion capture data and Black character base models. But I realized that my approach to creating this space was not necessarily correct. Mainly because representation is not enough. I did not want to perpetuate systems of harm on our bodies and on our movement and how we move in this space. So I needed to start to question what it means to be seen in these digital spaces and what it means to be liberated in these spaces as well.

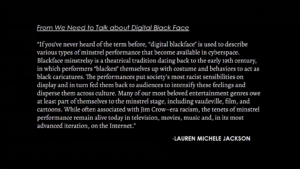

And yeah, so we first need to understand how our movements and bodies are already represented in the media and in the tools that we use. And this is just a quote from We Need to Talk about Digital Blackface. And I’ll just read it out. I’ll just read out actually like from half to the bottom.

Many of our most beloved entertainment genres owe at least part of themselves to the minstrel stage, including vaudeville, film, and cartoons. While often associated with Jim Crow–era racism, the tenets of minstrel performance remain alive today in television, movies, music and, in its most advanced iteration, on the Internet.

We Need to Talk About Digital Blackface in Reaction GIFs

So digital blackface is essentially an evolved version of blackface that’s seen in a lot of different social media platforms, but also in a lot of different tools that I’ll show.

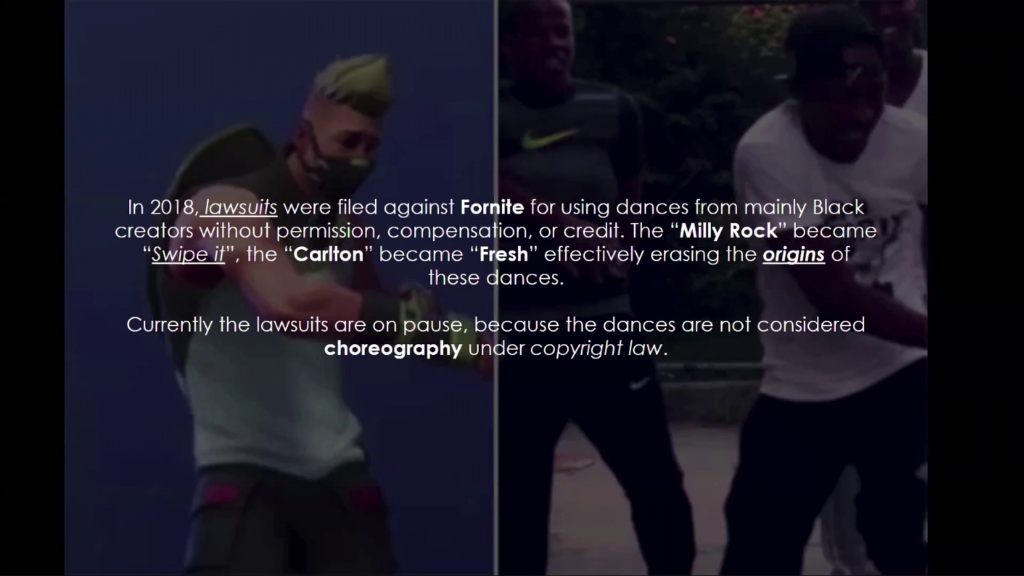

But yeah. During like the first few months that I started creating this space, in 2018 lawsuits were filed against Fortnite for using dances from mainly black creators without permission, compensation, or credit. So the Milly Rock became the Swipe It, the Carlton became the Fresh, effectively erasing the origins of these dances. However, currently lawsuits are on pause because dances are not considered choreography under copyright law.

So that’s essentially how it’s seen in video games. A lot of these dances can be bought on the platform and then applied to characters of various different races. So it just sort of really has this question of what it means to erase the origins of a dance, or like a community of creators

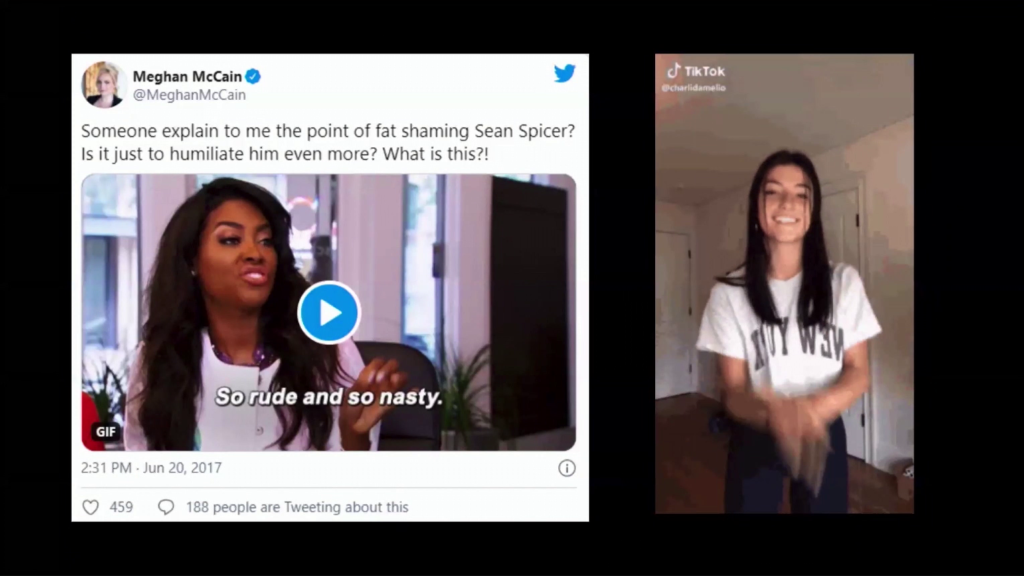

But blackface is also seen in memes and GIFs like on Twitter. And also in its most recent iteration on TikTok where a lot of different white creators have stolen different dance phrases from black creators on the platform while they’re getting a lot of different promotion and a lot of different opportunities from these stolen dances, a lot of the different black creators and black activists on these same platforms are silenced and surveilled at just really wild rates.

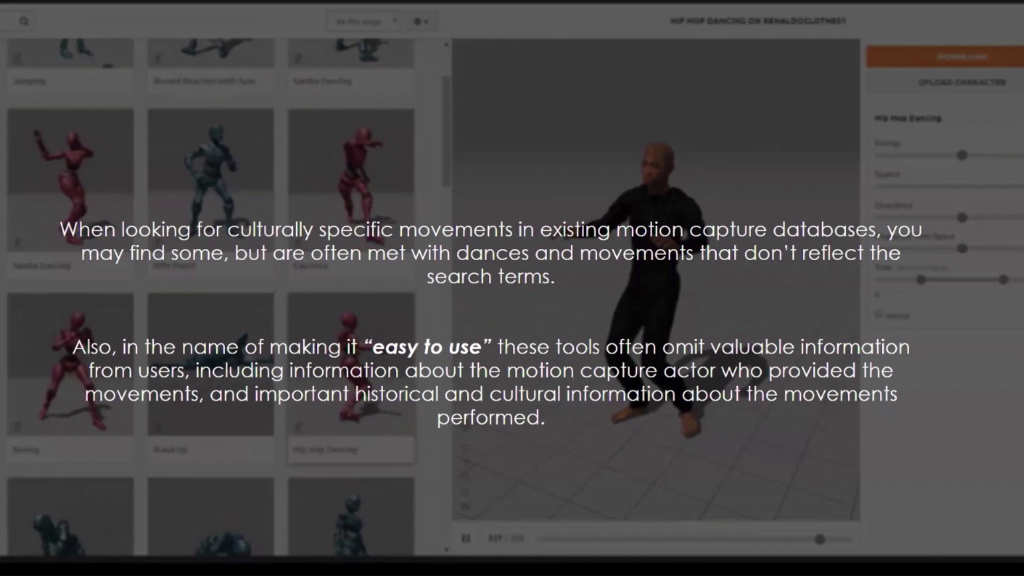

So that’s in social media space. But also there are different tools that don’t necessarily show us also. In this back picture GIF, this is a GIF of the dancer that I was working with doing this hip hop dance in this database. So this is actually Mixamo. And Mixamo is a free database that you can use. I do you reckon that folks who are interested in getting into animations use this tool. However, when you’re looking for culturally-specific movements in these existing motion capture databases, you may find some but are often met with dances and movements that don’t reflect the search terms.

So in the back there, the character’s doing a hip hop dance. But clearly that’s not hip hop dancing so it’s like, what’s going on? But also in the name of making it easy to use, these tools often omit valuable information from the users, including information about the motion capture actor who provided the movement and important historical and cultural information about the movements performed.

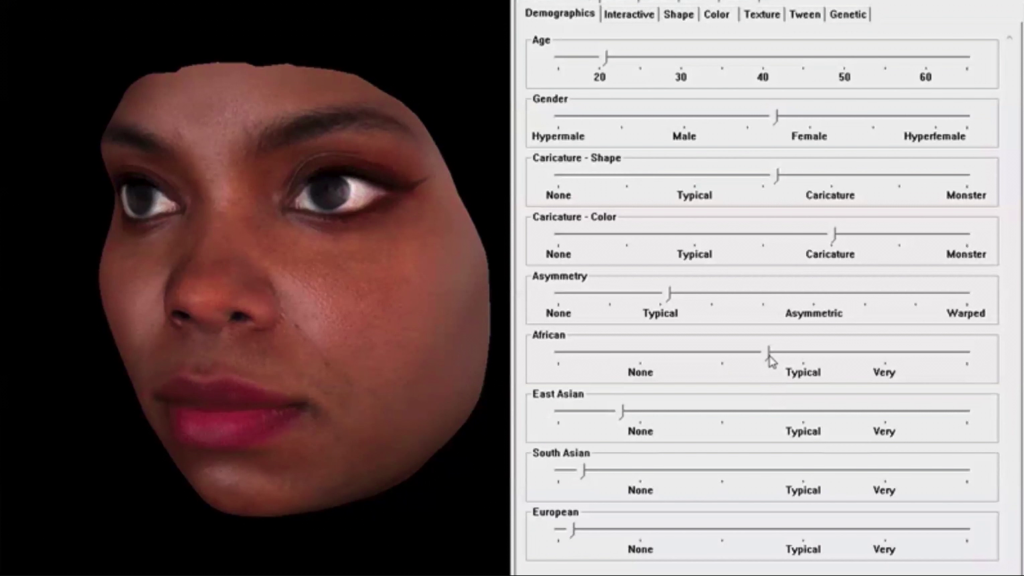

And this is another example of character creation software that I use called FaceGen which which is a plugin for Daz 3D. And essentially it’s really good for precompiling faces by uploading your pictures to this face. However, you can see on the right here with all of these different sliders, there are a lot of problems that arise. You can see that at the bottom half here, they’ve reduced a lot— They’ve created a lot of different problematic sliders for African, East Asian, South Asian, and European. So basically like, no. I have a lot of questions around what software…like…where did they get this information from for like, this is what makes you look more “African.” Or more East Asian or more South Asian or European. Where are you getting this information from, and also how can you sort of like take all of this range of data for all the different ways that a person can look into one slider?

But interesting enough, you can also see that as the features become darker in skin tone, they also associate that with them “feminine and masculine” characteristics of the face. So you can sort of see how these biases are implemented way more clearly than in a lot of different other softwares when it comes to how software developers see the body, see our faces and how we are.

And so the common thread of these examples is the oversimplification of Black people, our stories, and our lives. And this is really a network of systems that quantify and degrade our humanity in order to capitalize off of our existence and being. And so how do we combat that, the exploitation, the erasure, and the dilution of our culture and of our people? And what do the cultural reparations look like?

Black movement does not only represent our individual experiences, but it also represents our collective memory, transcending space, time, and white supremacist social structures. It allows us to connect to each other, our ancestors, our deepest selves. It gives us a space to communicate to our future. Black movement is also a technology, holding the stories of our existence across the Diaspora. And our stories and bodies are more than data points and avatars. They hold our humanity. And so it’s time for digital spaces and all of the physical spaces that we enter to reflect that.

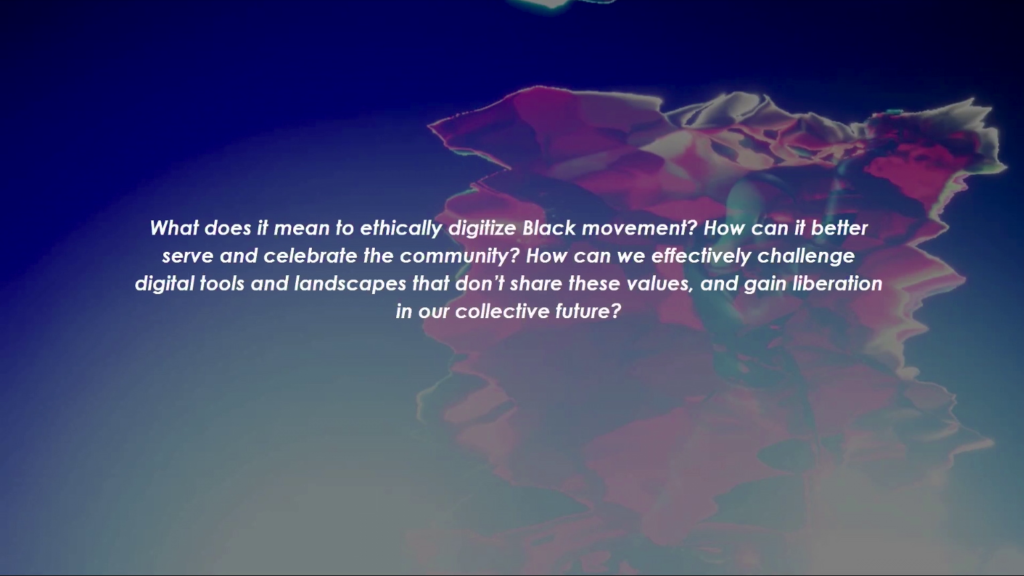

So yeah. I just ended up having way more questions than answers. What does it mean to ethically digitize our movement? How can it better serve and celebrate the community? And how can we effectively challenge digital tools and landscapes that don’t share these values, and gain liberation over our collective future?

In Black Performance Theory, Dr. Nadine George-Graves defined “diasporic spidering” as the multidirectional process by which people of African descent define their lives. The lifelong ontological gathering of information by going out into the world, and coming back to the self.

She does this by drawing connections to the evolving folklore of Anansi, to how Google and other search engines use web crawlers to find and organize new information for their growing databases.

So basically taking this idea of diasporic spidering, the Black Movement Library is a space for activists, performers, and artists to create diverse extended reality projects, a space to research how and why we move, and an archive of our existence. And we seek to grow this community through the use of performances, a various amount of XR experiences, workshops, conversations, and toolmaking.

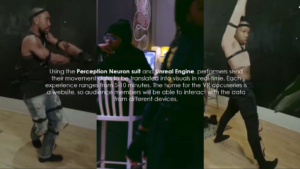

So basically, last year I started with creating a performance series which started with Nala Duma and Renaldo Maurice, where we used the Perception Neuron suit and Unreal Engine to essentially create these movement portrait landscapes. And I’m going to show you a video of what happened. However, essentially I did interviews with them both. And through those interviews about their movement journeys, I embedded those into the soundscapes that they performed to. And I did all this work as part of a residency at [indistinct]. And I’m just going to show a movement portrait that came from that.

So it first started as a live performance, so there’s a live performance with live projections. But I’m just going to show the movement portrait, which is a 2D representation of all of the movements from that performance.

https://vimeo.com/451558599

And just in the interest of time time I’m just gonna go back to the presentation. But yeah, they’re both ten-minute-long pieces for both Nala and Renaldo. And essentially you’re just learning about their movement journeys. And you’re learning about their moving journeys both through their own words but also as through their movement as well.

So they’re seen as both a live performance and a docuseries. And basically over four months I was just learning about their movement journeys and practices.

This translation into a portrait allows the movement to be re-represented as an abstract digital memory of the performance day. And and over the course of the year, I sat with the data, relearning both Nala and Renaldo through their movement and interviews, reconstructing and diving into the visual process as its own ritual. How do we translate digital representations of the self and others?

And that brings me into the workshop series that I’ve been developing for the past two years now called Understanding, Transforming, and Preserving Movement in Digital Spaces, which is a workshop to learn about extended reality tools in relationship to race, gender, and culture. And it’s been a traveling workshop, and basically I hosted it at Eyebeam, Afrotectopia, Pioneer Works, Barbarian Group, Barnard College, City College, and PBS POV.

And now it has an online version where I’m helping folks find all these different softwares online. Because we can’t use any different motion capture software tools, we’re actually using DeepMotion, which is an online AI-powered motion capture database where you can upload videos of yourself as long as it’s a full-body video capture of you. It can can use algorithms to decompile your movements into 3D animations.

And that brings me to the last thing that I wanted to talk about, which is Antidote. And this is a project in collaboration with Marguerite Hemmings. And we essentially created new portals of care using Zoom but also motion capture and Unreal Engine. And we were also able to collaborate with Rena Anakwe, Solome Asega, and Amber Starks. And we got a beautiful different soundscape and a really beautiful digital land acknowledgement from there. And I’ll just read this last part and then I’ll show you a clip of that. So yeah,

Antidote is an offering and a prayer. It’s an interruption, hacking, a portal, a medicine. A ritual response and physical undoing, of the lie that we are not our own, that we are not free.

And I just wanted to show a part a portion of this. This is Salome Asega’s part of the digital [inaudible]. [McMillian plays a ~3min excerpt of the following video, starting at 4:11]

https://vimeo.com/497811762

And I stop there for that one.

And, yeah. I guess the last thing that I just want to say is that this library is a movement that celebrates our history, our culture, and that serves our community to learn and grow as society evolves. And it holds us accountable in the ways we deal with Black people—our movements, our bodies, and our lives.

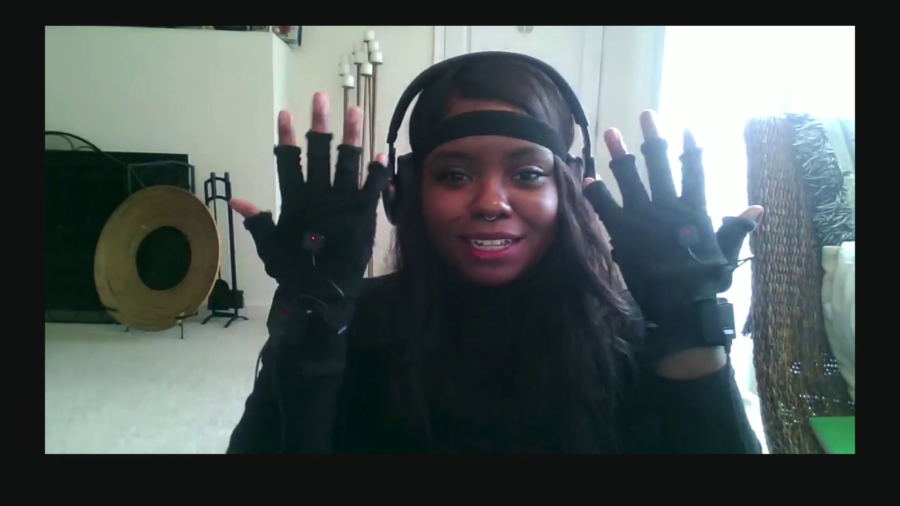

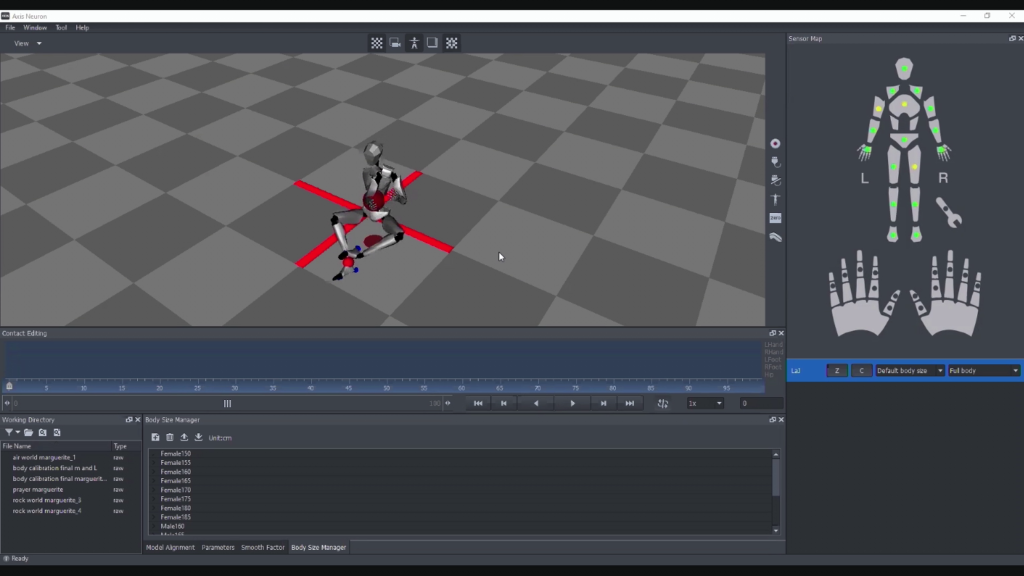

And I’ll stop the share now because I wanted to also show basically just how I’ve been making animation. So, yeah. Basically I’m wearing the Perception Neuron suit here. And this background stage is where I’ve been animating myself, doing all of these movements. And I was just going to share my screen to access Neuron.

Essentially my body’s all really bad right now. But essentially I would go through a calibration series. And I’ve been doing mocap using a Perception Neuron suit in my living room. So yeah, I think that’s where I wanted to end things. But thank you all so much for listening and sharing space with me. If there are any questions I guess we can do that now.

Golan Levin: Hi, LaJuné. Thank you so much for sharing your work with us. It was a great talk. I have one question. Which is, an aspect of what homemade is now…the digital homemade or the neo-homemade, is making things for oneself, one’s friends, family, and community. And your Black Movement Library is clearly coming from your community and back to it’s community. Maybe you…like I saw that sort of Christmastime or New Year’s video from Boston Dynamics, the robot folks, who had made these dancing robots that were clearly appropriating traditional Black dance movements from the 20th century. And we see Black dance, Black movement continually be appropriated, often without credit, now in robots even. And these are likely robots—I think in a particularly ghoulish way—which are almost like proto-cops that are gonna be suppressing Black lives.

I guess my question for you is, in making a Black movement library, presumably from a community and for a community, you’re distilling movements and also making them repurposable in a way. And there’s a risk that in making them repurposable, it’s gonna come out of your control and… Which is good and bad, alright. You want people to use it in ways you couldn’t have planned. But you also want to see it used in ways that are ethical and responsible to the material. How do you make sure that you don’t have dancing cop robots who are using your library?

McMillian: Um…yeah. And I guess it’s also why I changed my approach to the library space. Like I think in the beginning I was very much just interested in having just like a dataset and database of this stuff. But I realized really early on that I didn’t want to be someone who was perpetuating that space? Like we have a long, long, long history of exploitation of Black people. Like that’s literally you know…#slavery. You know? That is the basis of America. And so all that I can do is make sure that I am contributing to, stewarding, and working in spaces that are trying to or working towards abolition and what it means to abolish those ways of thinking about how we treat people, our bodies, and what our bodies can be and what our bodies can produce, creating and… Not even creating but yeah. It’s like, working to uncover and to rediscover and reestablish our connections to our own humanity? Like what does that look like? You know, we’re living in a lot of different systems right now. White supremacy, patriarchy, imperialism…all of the isms, right? And all of those isms really contribute to us dehu—us, all of us, dehumanizing ourselves in order to fit into capitalism. To fit into systems that commodify our bodies in ways that make it hard for us to humanize ourselves and to humanize each other. So what does it mean to create spaces and to reestablish those spaces, steward those spaces where that’s not the case, you know?

So that’s really what I’m interested in. I think that shift from database and seeing ourselves as just data, and seeing ourselves as human, as people who hold so much information, and trying to like— And I guess like the expansion from database to library allows space for us to be in many ways in that space. And allows us to really care for ourselves and care for each other in that space. And to really see ourselves and to see each other in that space, too.

And I guess that’s like the basis of the research that I guess I’ve been developing and working with. In the latest iteration of Understanding, Transforming, and Preserving Movement in Digital Spaces, we did a lot of movement work. So we did a lot of witnessing activities where we were mirroring each other over Zoom. And then basically I gave everyone prompts to define their movement, to define each other’s movement, and to really think about how those movements make you feel.

The last thing with this, I’ve been really thinking about what it means to transition from motion capture to motion witnessing. I feel like the term “capture” is so…it has just like really problematic…just like a really problematic etymology. This idea of capturing something, of owning something. Like what does it mean to really transform that into something new and different. And so yeah, basically the space, the library space…I don’t own it. I’m a steward of the space. I am a caretaker of the space. And I am trying to cultivate and help other folks come into the space, and through that we’re all having to do this work of decolonizing and decommodifying our bodies.

Levin: Thank you. This notion of motion witnessing and of the decommodification of movement data is really I think at this new essence of the neo-homemade.

With that, I have to close this. Thank you so much, LaJuné. In about four minutes we’ll pick it up with hannah perner-wilson. And so, everyone stay tuned. Thanks so much.

McMillian: Thank you!