Golan Levin: And we’re back. The last presentation of our afternoon sessions today is Professor Daniela Rosner, who is a professor in Human Centered Design & Engineering at the University of Washington. Her research investigates the social, political, and material circumstances of technology development. She’s the author of Critical Fabulations: Reworking the Methods and Margins of Design, which investigates new relationships between technology and social responsibility. Please welcome Daniela Rosner.

Daniela Rosner: Thank you so much Golan, and thanks also to Tom and Bill, and all the folks behind the scenes. I’m really looking forward to exploring some of the topics that we’ve seen over the past few days in a new context. And for me this is about sort of telling what I’ll be calling these impossible stories with design work.

And this has been sort of a longer project that a few years ago crystallized in a book that Golan just mentioned. And I’m gonna be framing some of the ideas today around these core questions of storytelling that we heard in hannah’s talk, for example, and many others that are about sort of what stories are underpinning our practices, and then what methods might be possible if we were to tell those stories differently.

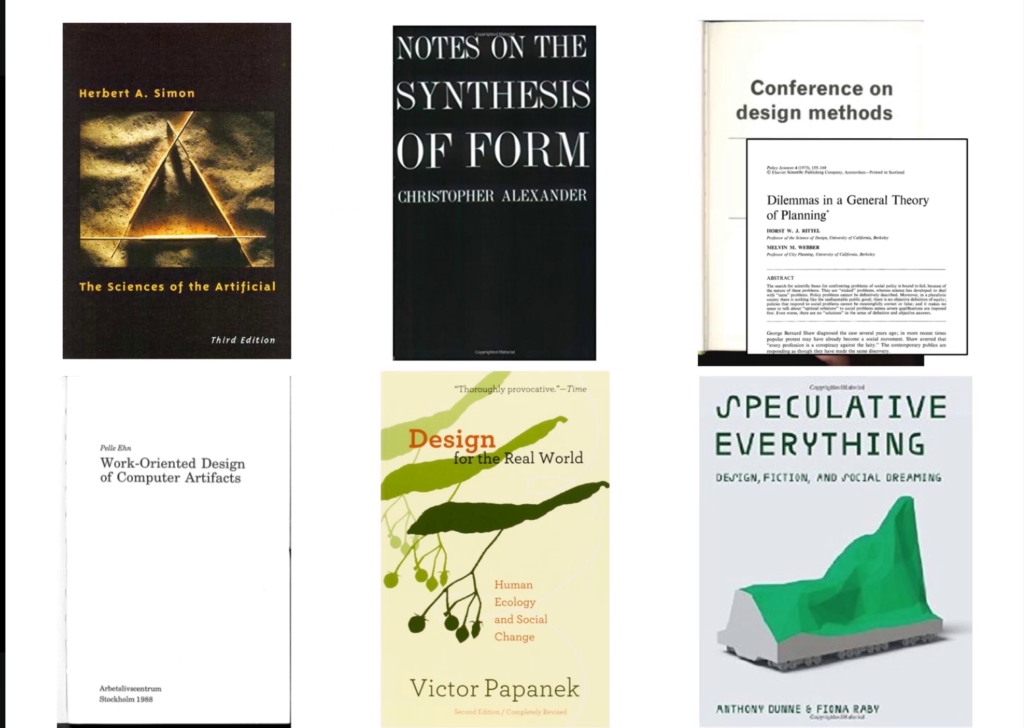

And when I kind of came into my practice, there was a lot I could kinda dive into to see and experience the stories of design. But in many of those pieces I found that there’s kind of a tendency to celebrate scholars like John Dewey, Herbert Simon, Donald Shure, and people that have had so much to offer the design fields but also who have had little to say about some of the more hegemonic or patriarchal legacies that have defined and shaped design work.

And over the past couple years there’s just been so many very new and exciting stories that challenge some of those existing canons. And I want to point to these stories as sort of a range of work that is really vital to what we might think of as the work of design which is futuring. But by doing so through the past. So by telling and accounting for what we’ve been through. And I’ll mention that actually one of these texts, The Social Life of DNA is authored by our new Deputy Director for Science and Society, Alondra Nelson that was announced today by the administration.

So, sort of speaking about these kinds of storytelling practices as a mood of fabulation, we start to explore what we do in design as a way of telling, retelling, this core work of speaking to the world around us. And for me that came out of thinking through a concept of fabulation in the scholarship of Saidiya Hartman and Vinciane Despret, who have separately discussed fabulation as a kind of storytelling that’s blending the real and the imaginary, and sort of building new worlds around them. So Saidiya Hartman coined the phrase “critical fabulation” in a vivid essay called Venus in Two Acts. And she’s describing sort of writing against the limits of an archive. These archives that are rendering, lives Venus who’s an enslaved woman, unknown or unknowable, their stories unrecorded.

And she writes, By playing with rearranging the basic elements of story, by re-presenting the sequence of events in divergent stories from contested points of view, I have attempted to jeopardize the status of the event.

And in that she’s imagining what might have happened, what might have been said, what might have been done. So this retelling from the past.

And in a kind of separate account, What Would Animals Say If We Asked the Right Questions?, Despret is describing a kind of complicated relationship between animals and scientists, where they’re kind of inverting stories told about science, with science. So she’s writing, To create stories, to make history, is to reconstruct, to fabulate, in a way that opens up other possibilities for the past in the present and the future.

So again linking these stories of chronology.

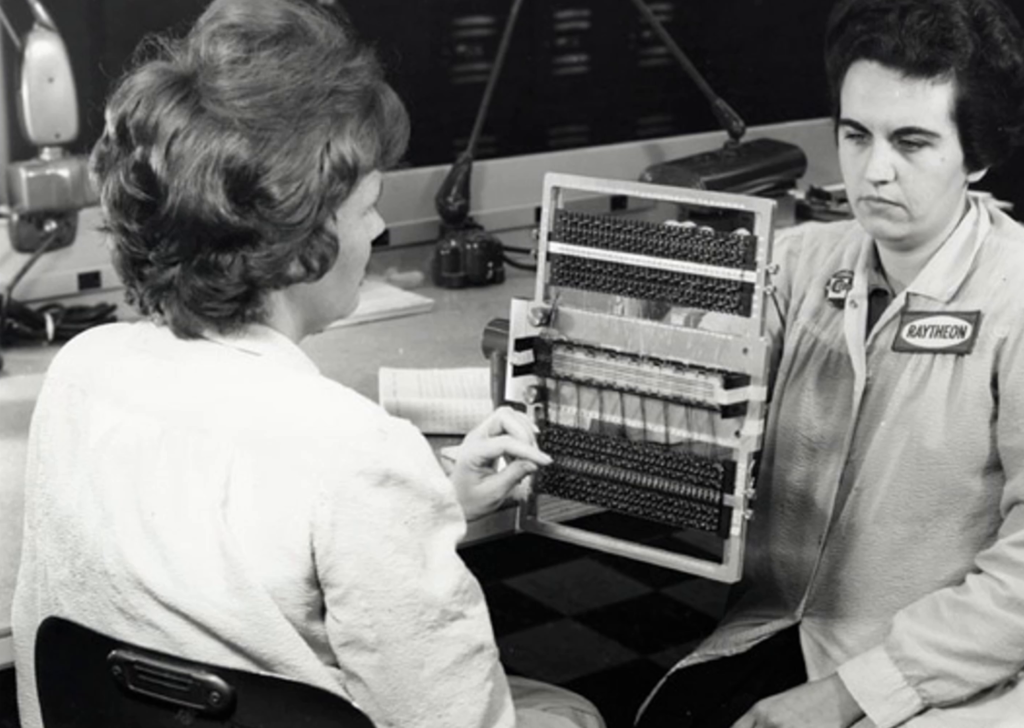

Now, bringing a kind of fabulation or fabulatory practice to design, I want us to try to understand design a bit differently, as a kind of multi-bounded process that starts as very small gestures and begins with doing the impossible. And what I want to start with is actually a small clip from a project I began with collaborators Samantha Shorey, Helen Remick, and Brock Craft. And what we began with is just a moment in a 2008 miniseries that was as you can see showing two women seem…to be rolled-up sleeves, passing a kind of needle through this sort of grid of eyelet holes.

When I first saw this, as maybe you might think, this reminded me of another kind of practice, one we’ve seen over the past few days, one of weaving, right. It’s almost a textile they’re making. But here the weaving is using unconventional materials like wire and magnetic rings in this odd loom. And you’re seeing this weaving happening in a kind of you factory setting. And over the scene that you just saw is the voice of a managing director named Richard Battin. And he says, “We called this the LOL Method, the Little Old Lady method of wiring these cores.”

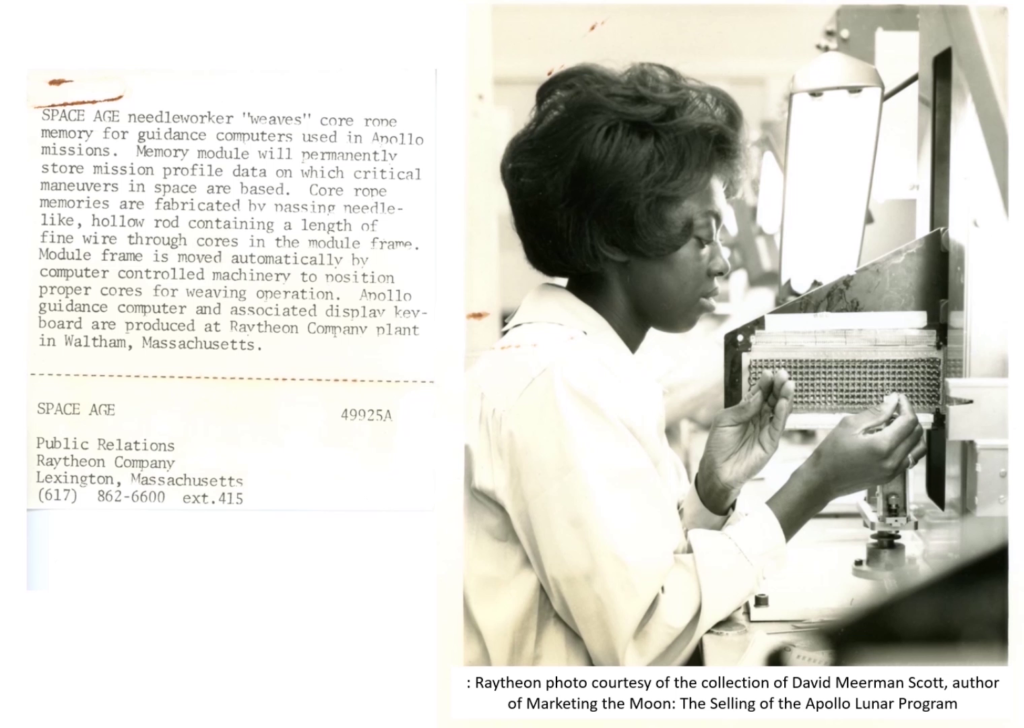

So this footage is only a few seconds long. It’s silent if not for that narration. And it’s one of the only surviving accounts of the women who physically wove software for the Apollo missions during the 1960s.

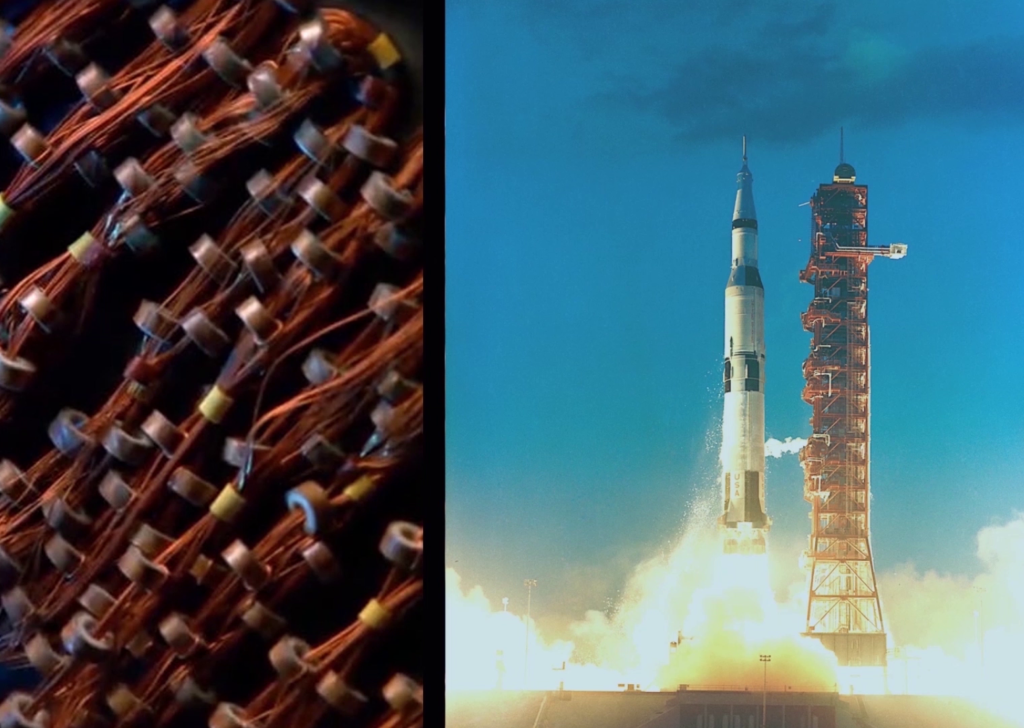

So I was mentioning Richard Battin because again his voice was narrating the story of the operators who were doing a specific kind of work. They were weaving the software for the Apollo missions during the 1960s. So they were threading wires around and through doughnut-shaped magnetic cores that were called the core memory.

And this is a technology that was pretty prevalent across the 1950s and ’60s, and it was the principal mechanism by which computers were storing and retrieving information. So if you think about a wire going through one of those doughnuts, would create a 1, a bit. And then going around it would create a 0, bypassing it.

So at this moment, computers looked pretty different from the computers we see every day. These were massive room-sized machines. This was in 1961. There was punchcards that were used to run them.

And the contrast of what they needed to produce to fit a computer in into the cone of a rocket, they needed a technology that was obviously easy to condense but also that could withstand extreme vibrations, like extreme temperature changes, and that was light enough to be carried to the Moon.

So most of what we know today about this mission comes from stories that were told by Battin, right. And what we began to do with a kind of fabulatory approach in design is to look at the wider story and start to ask how we might share and think through a retelling of it through a material process and making.

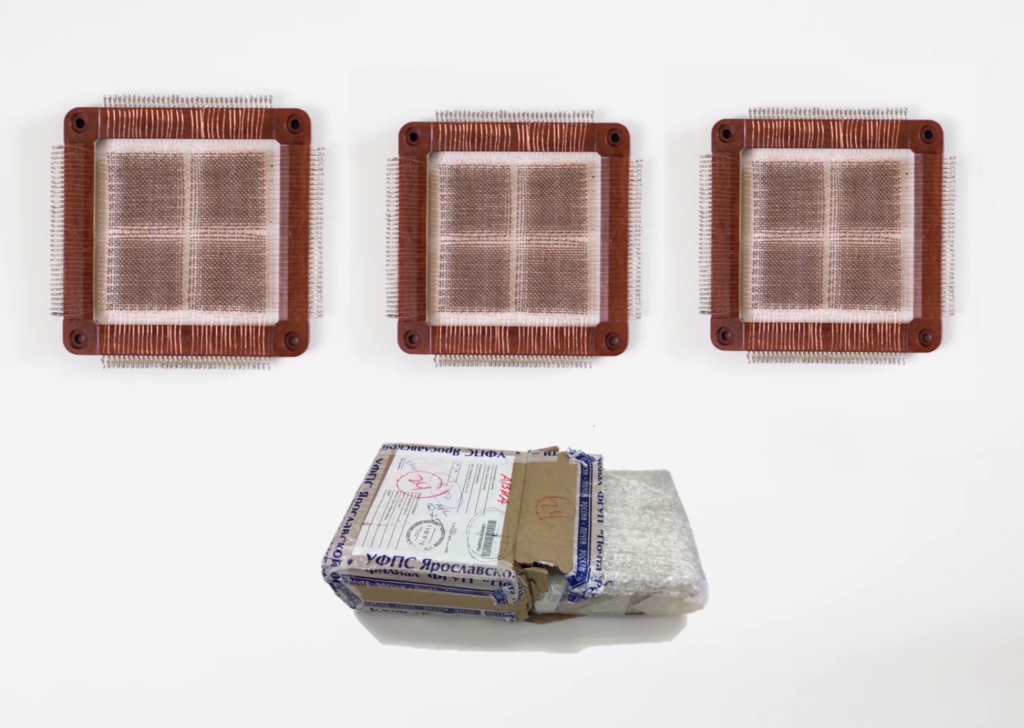

So, we began to look at the wider process of core memory redevelopment, which included these very cool P2P core memory planes I ordered on eBay. And sort of holding them in my hand they reminded me of another form of sort of memory-making of sorts, a kind of praxis of quilting.

So in the next few months we developed what we came to call a core memory quilt. This was a quilt that was made up of the patches that were handwoven, still, and were made of core memory themselves. So it was sort of creating these new points of encounter with those older materials.

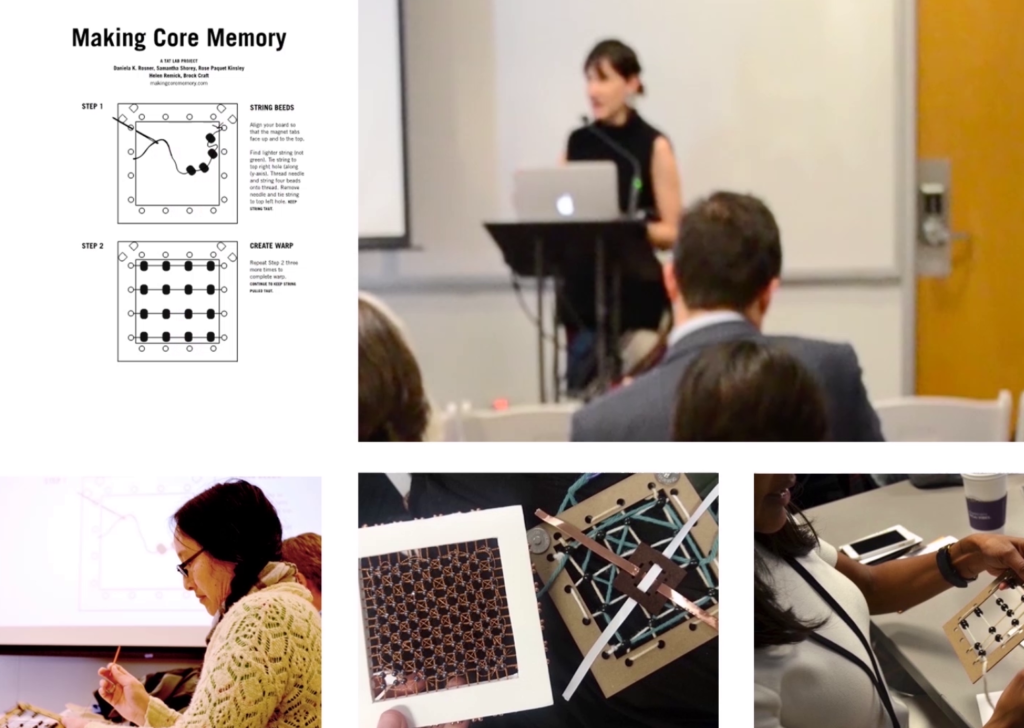

So, working across a range of archival and current modern technology—Arduino boards, looking at patents that would have shift across the 1950s and ’60 to show what sort of missing figures, right, the people operating these machines, how those bodies were working with them, and exploring the very scales of production that the core memory was built on. We created a kind of traveling object that we took the to a series of workshops, from Maker Fairs, education conferences, history of technology spaces.

And in this series we asked people to assemble something we called kind of patch kit. So we gave them a core memory kind of board loom, and strings, beads, these sort of kitschy almost craft materials. And with them, they were able to access our archive of media material. So we had a collection of first-hand accounts of core memory production that we collected along the way. And plugging the patch into the quilt then would play aloud these oral accounts of core memory.

But as they did this, of course we had to tweak those as well. So we created a kind of bot-like Twitter stream that would replay those same accounts of the weaving process. So for example one tweet said, “The female operators were good at it, and those that stood around telling them what to do were terrible at it,” from Edwin [B…?].

And in one moment in this process, Helen Remick, who was a master quilter collaborator, reflected on this object as a contrast to the microchip. She said, “I’m having fun realizing we’re creating a macrochip. We could continuously open it up, put our bodies inside it, and repair it ourselves. It is very different from our relationship with modern-day electronics that tend to be so finite we cannot experience that kind of care.”

At the workshops we ran it didn’t take long for folks to bring up this kind of odd relationship we were drawing between weaving, textile work, and engineering and technology. So people wanted to know a bit about the language we were using and how we were making sense of it. What did the operators call themselves, for example. And hoping to shed some light on this, I decided to reach out to a man named Frederick Dill, who is a pioneering engineer, he’s a co-inventor of the semiconductor laser. And I’d been in contact with him throughout this process.

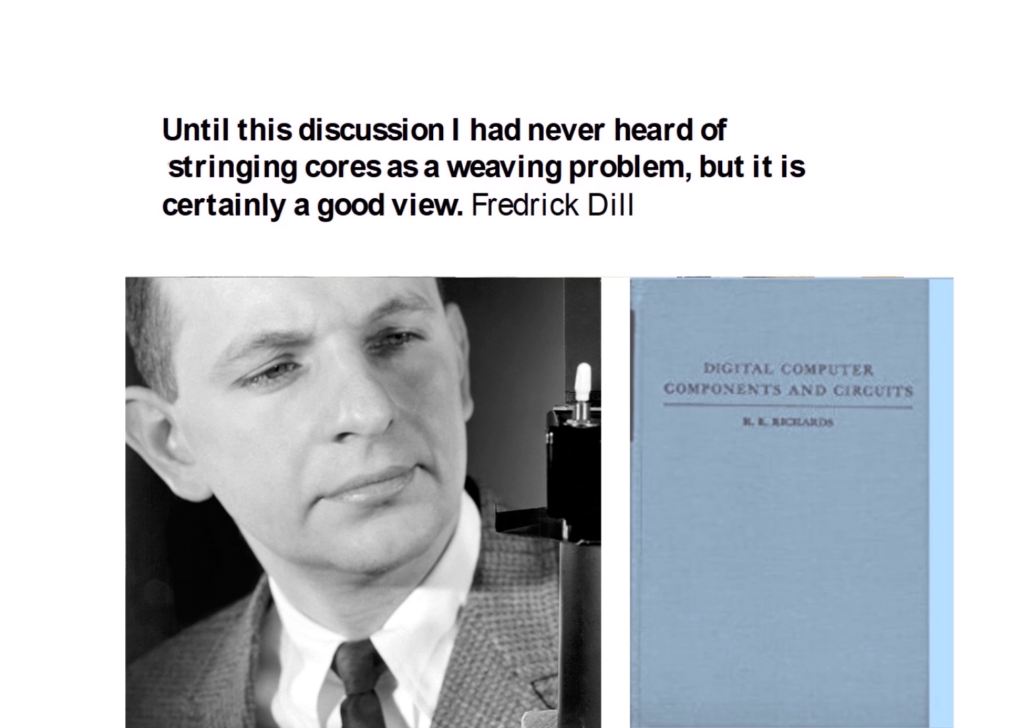

Dill recently sent me a 1957 volume of Digital Computer Components and Circuits, and he had created this beautifully typed, printed note that said, “Until this discussion I’d never heard of stringing cores as a weaving problem, but it’s certainly a good view.” The cores are those doughnut shapes.

Then I asked him what he meant by this comment, and he replied in email, “You have focused on the threads, where I focused on the cores. Your focus on weaving is an equally valid viewpoint, but a different one. It sort of assumes that some particular configuration of weaving will produce what is needed, which is totally correct.”

So looking at the weaving alongside the electrical cores we saw an almost new attention to this labor of production alongside the thing. And that meant identifying the weave as a pivotal innovation, like he said, the mechanism that is needed, in Dill’s words. This is a really unusual insight not just because of its widespread omission from core memory literature but also it’s a deeper recognition of embodied practice, or bodies at all as core contributors to engineering. And Helen Remick again reminded us one afternoon quilting is similarly not just hen work, it’s not just back work, net work, it’s also new work, joint work.

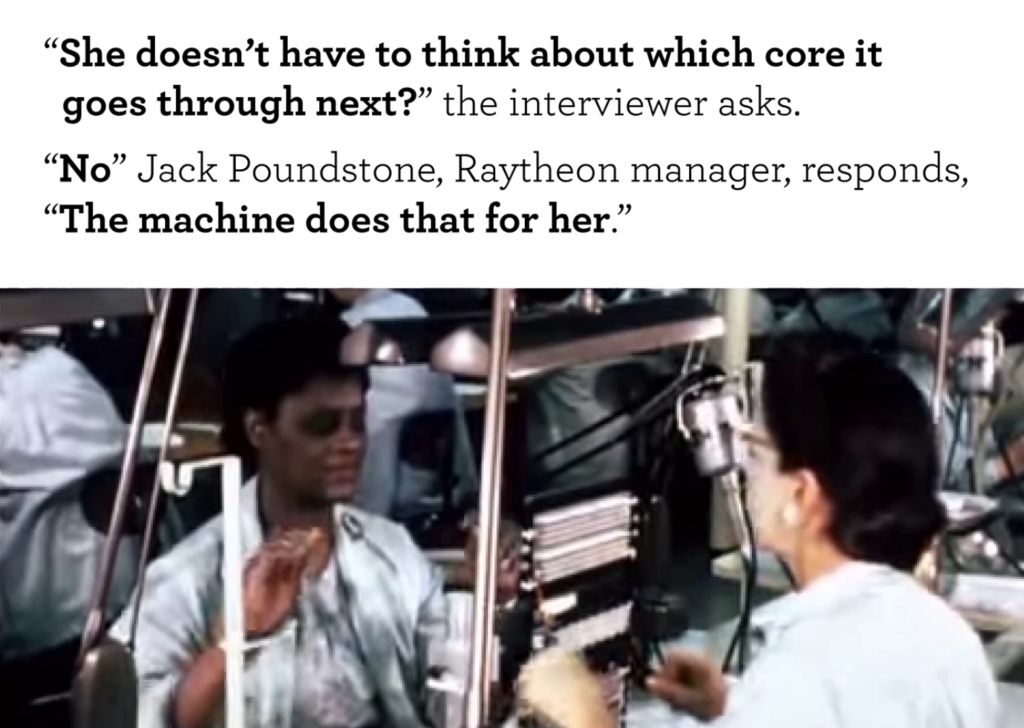

So as we built the quilt we encountered the process in ways that change public accounts of this mission, such as the MIT museum footage that said—the interviewing journalist, “She doesn’t have to think about which core it goes through next?”

Jack Poundstone replies, “No, the machine does that for her.”

These are portraits of kind of unthinking executors of code rather than inventive contributors, which sort of reverberate throughout these public accounts.

So this kind of reminds us and cautions us almost against what Lisa Nakamura has talked about, as you look inside a machine you might see the Intel dancing bunny-suited clean room workers happily making chips for free. She says instead, Looking inside digital culture means looking back in time to the roots of the computer industry and the specific material production practices that positioned race and gender as commodities in electronic factories.

So this project is really thinking about design methods in a way that positions it as challenging histories in ways that not only reassert divisions between the cognitive and the manual, but they’re hiding all the classed, gendered, racialized labor within innovation work. So this is about reckoning with those metaphors and conditions.

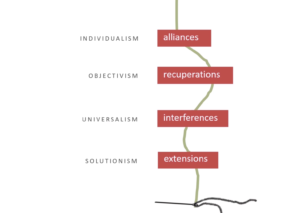

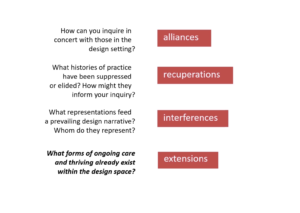

And drawing out critical fabulations in this process was a process of reckoning. So what helped it us think through is a kind of alternative to many of the sort of typical dimensions or tenets of design.

So a set of habits of being that might result in other ways of making things. Instead of individualism, we could ask how might we inquire in concert with those in design settings. And instead of objectivity we might ask what histories of practice have been suppressed or elided. And other than a universal view of the world, can we look at the intricacies and and ask what representations feed a prevailing design narrative, and who do they represent? Who are those people? And in contrast to a solutionist gaze we can think about what forms of ongoing care and thriving already exist within a design space.

![Design Fabulations: Collaborating with Ghosts [Alden Foster 2015]](http://opentranscripts.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/art-code-homemade-daniela-rosner-036-1024x728.png)

So taking this fabulatory practice as a way of telling stories, we can start to kind of awaken these silent ways of knowing, and even deconstruct design methods to open up different possibilities.

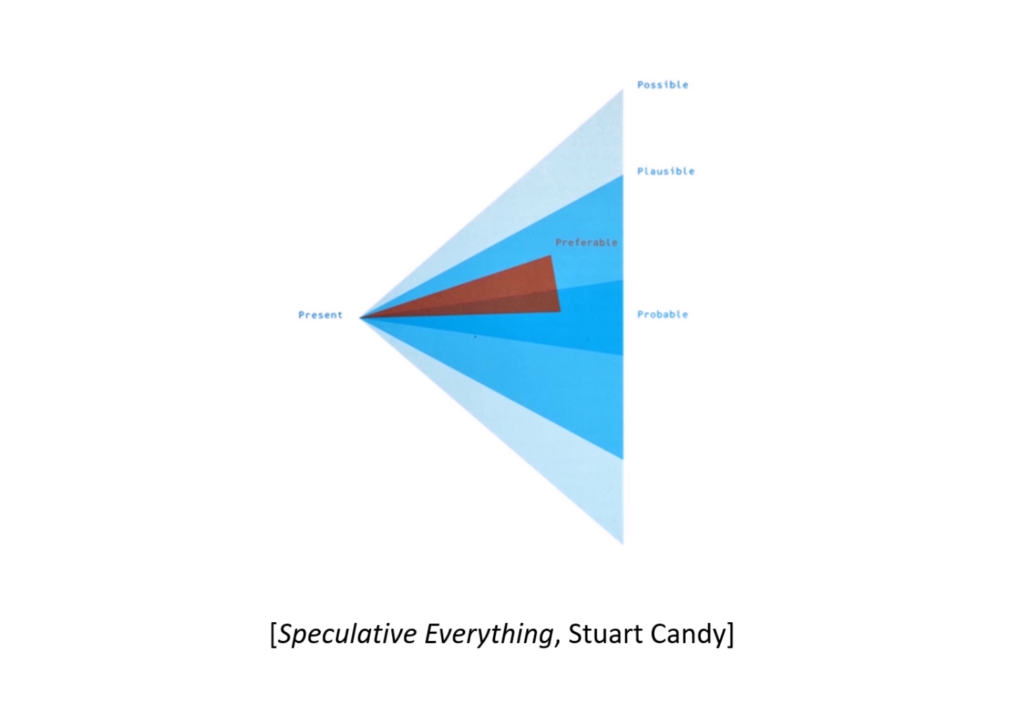

And as I kind of close, I want to just bring this back to some of the kind of ways that in sort of a standard design program, how you would speculate on the future. And one way kind of comes down to something called speculative design, where there’s a cone and you’re in the present right now. And there’s many ways you can go. You can go to the probable, the plausible, or the possible. And then as Tony Dunne and Fiona Raby re-represent this in the image here, there’s the preferable that offers a kind of new way of seeing. It’s an interesting way to predict.

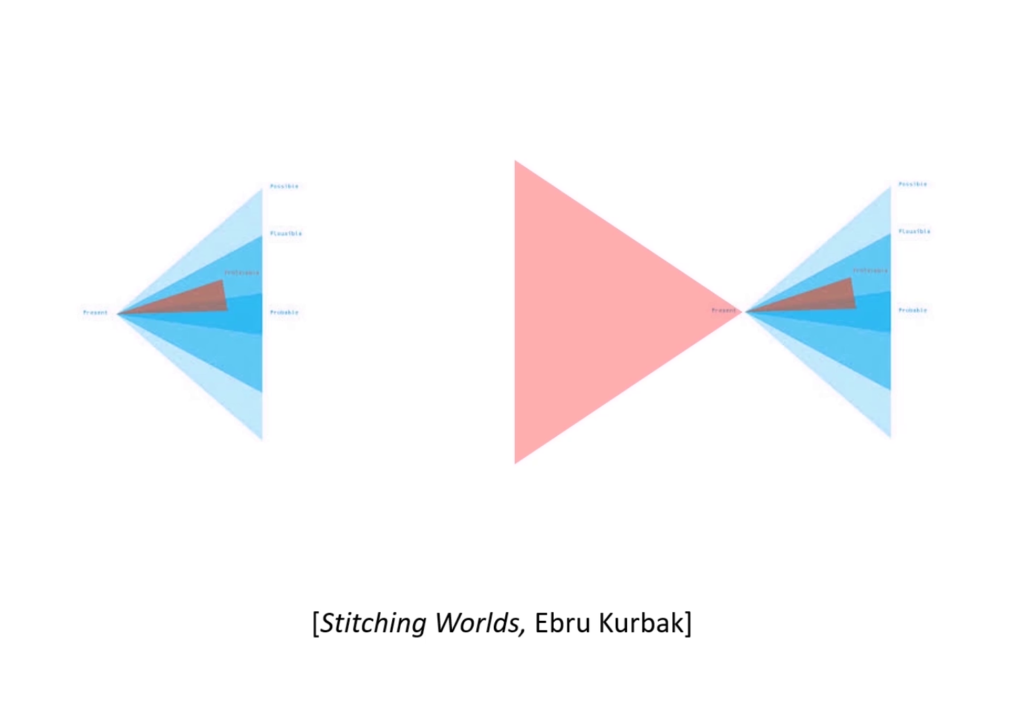

But as Ebru Kurbak recently contested, there’s a trajectory from past to present that doesn’t look at the influence of the past, right. She’s trying to highlight that there’s new ways of seeing openings and closures that come from the process of looking backward.

And I’m going to suggest that maybe fabulations is more than one perspective, right. It offers a way of thinking about the past in a way that’s not just about filling gaps but about the kind of haunts, the ghosts, the traces that are still acting in the world today. These are the silences that are still— In the context of our core memory work, you’re seeing the computing field continually reentrenching inequalities in the present. And those silences are bearing witness to that and contributing.

Now, you might contrast a speculative lens with the more typical mode of trajectory from empathy to testing, and I would suggest that in fact many of those same erasures are happening because of an absence of reckoning with the past. That we continue to not see their operation today.

So when we look at the world around us and see you know, AI that are continually coding ideas of servitude in sort of gendered or racialized forms, or we’re looking at misinformation, disinformation, that fills our devices, allowing for unaccounted tech firms to roam free, what what we might be feeling like is we’re walking along a kind of Möbius strip, right, we’re always moving but there’s nowhere to go.

And I want us to kind of move through a different picture of design, maybe an affective, emotional journey. What if we moved from design apathy to design optimism, to design pessimism, and finally design reckoning. A kind of journey through a design process that acknowledges that many times we don’t have many options of how to create a better world, but that we need to still reckon with those existing and prevailing and injustices.

So I’ll now end this talk with a kind of opening for asking what “what is required to imagine a free state or tell an impossible story,” a quote from Saidiya Hartman, opening up the possibility for doing otherwise in the world today.

And with that, thank you so much and I really look forward to questions.

Golan Levin: Daniela, thank you so much. So, there are questions. And the first one I would like to send your way is from Lea Albaugh, who’s one of the curators of the Art && Code festival. And she says— We talked about this a bit in the chat for Laura’s talk earlier. She’s curious about your take on the tightrope between positioning fiber arts practices as uniquely marginalized histories, and the knowledge that highlighting that can entrench the problem. And she goes on to say, “I know I—Lea—grapple a lot with the ‘Did you know that weaving was the first computer,’ which is sort of wrong in a way that misses the interesting points but fundamentally well-meaning.”

Daniela Rosner: Mm hm. So I mean, there’s kind of multiple questions in that. There’s the retelling of a technical story in a way that that you might not think is technically correct, right, in the sense that citing weaving as the origin of computing, well, is it? Does it matter if it is? And I think some of the sort of of practice of retelling is also about really grappling with the sense that the wrong is also important, right. So calling out a particular story like weaving as the origin, like what work does that do? Does it allow us to to maybe imagine things differently today? To imagine like our inheritance in computing being one of textile work? How does that open up different kinds of relationships to maybe intimate relations to the technology that’s so closed like our automobiles that we have no idea how they work today. And that I think is a grappling in the right to repair movement, that started to say no, we need to have the right to open up those cars and understand how they work and repair them ourselves, because corporations are not allowing us in. And in fact, with textiles as we’ve seen with many other projects today, it’s interesting to see those automatic intimacies that are built into the legacy of craft. I would say they’re productive in either way.

Levin: There’s another— One of your last slides had four different types of design. Could you mention again, what— It was a sort of black and white and yellow slide with four drawings.

Rosner: Yeah.

Levin: What were the four names? For the sort of—towards the future, you were saying.

Rosner: Exactly. It’s sort of this emotional journey through design where instead of you know, design empathy we start with design apathy. Many people just don’t care about design because most people do not consider themselves designers, right. And so moving from there to a space of optimism where a lot of—this is a sort of trajectory that I often see with students of mine where you sort of get excited and interested and you know— So you see yourself as implicated in the design world. And then we notice all the challenges that can no longer be denied that are populating our news feeds, right, of disasters of design. So that’s design pessimism. And then finally design reckoning, where we kind of acknowledge them all.

Levin: This is a term I haven’t heard before. And one about which Kate Hartman asks, “How might design reckoning be best introduced as a broader practice?” It’s a fascinating term, and it’s got a…got an edge to it.

Rosner: Cool. Yeah, I’m writing— That’s the title of something I’m writing right now. It’s a longer, book-length project, and I’m really— I mean, if anyone’s interested in chatting, I have much to say the topic.

Levin: Could you explain design reckoning some more, and what—

Rosner: Yeah. Sure. So, reckoning being…there are many uses of the term. It’s a pretty fascinating term. It has a pretty interesting heritage in religious text, right. If you think about the day of reckoning, what that means to be sort of accountable and accounting for a massive change. But reckoning is also not one with resolution. It’s not something where you’re looking for a fix. And so it’s kind of…in simplest terms, a kind of contrast to the technofix, right, where we’re just…we see that we can solve something with a different design. Whether it’s of a thing, or an institution, or you know a world like our society, there’s a lot of this thinking through of a kind of simple fix to the problems that we have. And as tied to the theme of this talk, I think it’s much more about grappling with our past and our present, and how those relationships work to…can define in not determinative terms, but really shape the world that we can be. So, reckoning again is this critical, engaged, effortful work to be with our world, and to see you that we can never fully change it but we can try in small ways again and again. So it’s actually a more humble approach to that kind of work of revision or revolutionary change.