Arielle Johnson: Hi. I’m Arielle. I’m a scientist. My job is to work with cooks to figure out the science behind food and cooking. But something that we’re also interested in with my job is using the knowledge that we produce by doing that to improve the world.

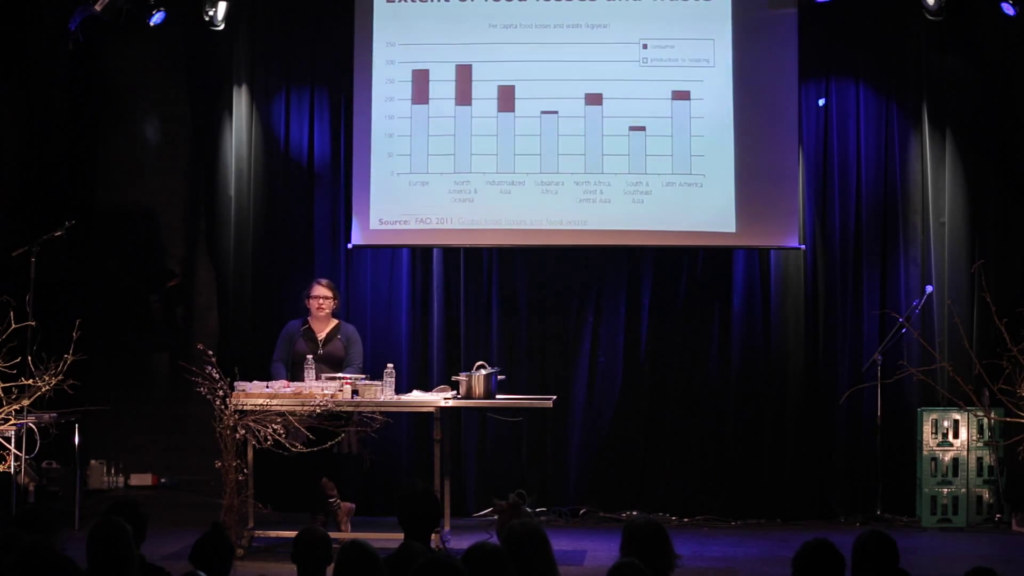

So, you may have heard about food waste, including just now. But it’s a big problem in the world. Each year we waste about 1.3 billion metric tons of edible food. And that happens on every continent, at every link in the food chain. From farms, to distributors, to markets, to people’s home kitchens, and restaurants. So, it’s a complex problem that’s not going to be solved by any one idea.

Some parts of it, like cosmetically less-desirable fruit and vegetables can be dealt with by developing alternative markets for this produce such as Fruta Feia in Portugal. And these provide a way for these to be distributed bypassing the inefficiency of the conventional ones, which tend to follow EU regulations that say that a strawberry that looks like that, or a Kirby cucumber can’t actually be sold because it doesn’t pack well.

But tonight I’d like to tell you a little bit about how our experiments in fermentation have given us some really interesting tools for dealing with food waste.

So this is where I work. It’s four shipping containers in the back parking lot of Restaurant Noma. We built this lab to have a space to study food practically, not so much to make new dishes but to make new knowledge. And we built a lot of it ourselves, as you can tell from the wiring job on our thermal controllers. And this is Noma head of R&D Lars Williams looking quite skeptical about my painting abilities.

But you may be wondering what I’m doing in a semi-apocalyptic bunker in a parking lot behind the restaurant. And I’m not gonna lie, a lot of the scientists I went to grad school with kind of shrug and say like, “Hey, you really don’t need a PhD to do what you’re doing, to work with a restaurant. But if it makes you happy I guess…it’s your life.”

But really I left the academic system to work at MAD. Not because I wanted to stop doing science but because I think that some of the most powerful and interesting and innovative new ideas about food are coming out of restaurants, not out of university labs. [applause] Yeah. Yeah.

So spaces like the one that we built let us experiment with things like Aspergillus oryzae. That is this moldy stuff back here that’s rich in culinarily useful enzymes. But more broadly speaking, it let us combines scientific and restaurant approaches to make more, better knowledge about food, faster.

So, the reason that we have this mold is that one of the big projects that we’re working on is fermentation. And fermentation is the transformation of food ingredients by microorganisms such as bacteria, yeasts, and molds. It occurs spontaneously. A lot of these microorganisms are just like in the air, on our skin, on various other surfaces. So it’s been a part of human gastronomic history since we’ve been eating fruit or making grain porridges or milking cows.

But it also creates complex new flavors in ingredients that we’d otherwise overlook because they’re bland on their own or we consider them waste products. Basically it turns trash into treasure. And in doing some of this studying fermentation, I recently went to Japan, where I wanted to visit the grandmothers and guys with gigantic vats of squid sauce out their back sheds, and people who’ve been making miso for ten generations, to learn some of the things about fermentation that I wasn’t gonna learn in books or academic papers. So here we’re grinding some soybeans to make miso.

Japan is one of the most food-obsessed cultures on Earth, and a lot of extremely delicious things are made out of materials that we might otherwise write off or overlook. So, this is a winter turnip pickle. A lot of the winter tsukemono, or pickles, are made of turnips. This one’s called [suguki?]. And through a series of saltings, and pressings, and careful fermentations at different temperatures, the turnip’s transformed into this incredibly complex, rich, meaty pickle. And the greens are some of the best part, and in its raw state the greens are sort of more of a throwaway material. And each of these pickles retails for about like seven or eight dollars apiece.

This is another turnip pickle called senmai. If you can see it it’s sort of like lots of overlapping slices. And this is a turnip and kelp pickle. Seaweeds are a good example of a plant that grows in lots of different places that a lot of cultures don’t even really consider as a food source. But in sort of natural resource-poor areas like Japan, they’ve recognized its potential and developed it into a really flavorful and highly prized food source. Basically to make these delicious products they’ve taken an unsexy vegetable and weed, and by recognizing the inherent potential for flavor in these ingredients, they’ve developed techniques to realize that potential. And a parallel to that, what we found in Copenhagen is that we can use fermentation to realize the full flavor potential of many different kinds of waste and food scraps.

So since it’s the evening, we thought you might like to have something to drink. I think that was passed around beforehand. So, there’s some whiskey in that drink, if you haven’t had it yet. It’s at the back, in part because our jailhouse bread wine isn’t quite ready for prime time yet. But 67% of that drink is pumpkin scraps that we fermented into vinegar. Yeah.

So when we’re fermenting, basically what we’re doing is a sort of microenvironmental engineering. We’re creating conditions using salt and temperature and oxygen that allow the microbes that we want to grow and flourish and transform food into something delicious. And we’re using all different kinds of techniques like making vinegars, doing lactic fermentations, making kombuchas, and then doing like protein-rich fermentations using that mold that you saw before to make lots of enzymes and then break down a legume or an animal protein.

But basically the takeaway that I’d like you to have from this is that… I hope you can tell by tasting that dealing with waste sustainably doesn’t have to be a big pain in the ass. It’s just about rediscovering the ways that these waste and scraps can be delicious. And to be honest you know, working together we only stumbled upon waste fermentation as a technique because we were already interested in fermentation. Because fermentation is delicious. And to be able to get the sort of tangy and umami and other flavors that you get from fermentation using Nordic ingredients, it became necessary to learn about enzymes, and molds, and spores, and fungus, and different bacteria and oxygen levels and salinity. But once we had that knowledge and were using it regularly it became trivially easy to apply it to the problem of waste fermentation, or dealing with food waste. But if we’d approached food waste without having developed that appreciation for flavor to begin with, we wouldn’t have been able to just brute force innovation out of nowhere.

So some of the stuff we want to do going forward is figuring out some of the more complicated things about fermentation, like how do different temperature profiles affect the enzyme levels in our molded barley that we then use to make a leftover meat or leftover bread soy sauce, and how do those enzymes eventually impact flavor? Other questions like that. But what [indistinct] comes down to is that if we’re going to tackle waste in a sustainable way, and other food issues in a sustainable way, we have to do it with an eye to flavor. And speaking as a scientist, nobody understands flavor and deliciousness better than cooks do.

As a little bit of circling back, at the very first MAD here in Copenhagen, this is in 2011, David Chang also gave a speech about doing fermentation at his restaurant. He’s an American chef. He has a restaurant called Momofuku in New York. And one of the things that he said about having worked with microbiologists from Harvard is that oh well, we need them more than they need us. Which is a nice sentiment, but I think it’s actually the other way around. Because we’re standing here in 2015, we have greater technical knowledge of food than we’ve ever had before, and we also have the patenting of indigenous plant’s genomes for the sake of so-called technical progress. And bee life about to be wiped off the planet from pesticide use for intensive agriculture. And the making and eating of Soylent instead of real food. Food waste, as we said before. Antibiotics about to become a thing of the past because of the way that we concentrate our [lot?]-based meat cultivation.

So, not to be a fatalist, but if these results are what we get from combining food and science the way that we’ve always done it like, yes we absolutely need cooks as part of the scientific progress. So if there’s any takeaway I’d like you to have from this it’s that seeking out knowledge, the impetus for knowledge that sticks, and tools that enable it sustainably, all comes down to flavor. And so please enjoy your drinks, and tip your waitress. Thank you.